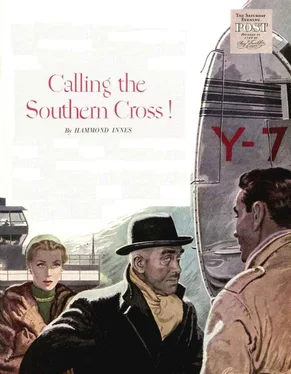

“Do you mean Bland and his son?” I asked him.

“Ah’m no saying anither worrd,” he replied. But I saw by the glint in his eye that I’d hit the nail on the head.

“And the Sandefjord man?”

“He’ll be all reel noo.” He hesitated, shuffling his feet awkwardly. “Ye’ll no pass on what Ah said jist noo about their wanting to get rid o’ one or two pairsons?”

“Of course not.”

He suddenly grinned. “It’s the deil when ye’ve got factions like this an’ they’re cooped oop togither in a Godforsaken place like the Antarctic for moonths on end. It’s no so bad on the catchers and the towing ships. Each ship is either Tönsberg or Sandefjord, wi’ a smattering of Scots in the engine rooms. But I tell ye, it’s no sa gude on the factory ship.”

“You mean they’ve a mixed crew on the Southern Cross?” I asked him.

“Aye. An’ it isna only the crew that’s mixed. It’s the flensers and laborers that’s mixed too. And they’re a violent bunch.” He shook his head gloomily and turned to go.

“Perhaps you’d care to have a drink with me later,” I suggested.

His face relaxed into a dour smile. “Aye, Ah would that.” And he slid down the ladder to the deck below.

About seven o’clock Bland pulled himself up onto the bridge. Hi face was blue and puffy, the blood vessels showing through the skin in a mottled web. “Hub the Southern Cross given you her position yet?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “I got a message from Captain Hide this morning.”

“Good.” He peered over the helmsman’s shoulder at the compass. “Hear there was a fight,” he said.

“Yes. Sandefjord versus Tönsberg. Tönsberg won,” I added.

He gave me a quick glance and then leaned his heavy bulk against the wind-breaker. “Women are the devil,” he muttered. I think he was speaking to himself, but I was to leeward of him and the wind flung the words at me. “You married?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

“A man’s no match for a woman,” he said, looking at me. “A man’s mind and interests range. A woman’s narrow. They’ve a queer, distorted love of power, and they’re fonder of their sons than they are of their husbands.” He turned his head away and stared down at the sea where it was beginning to break inboard over our plunging bow.

“What exactly are you trying to tell me?” I asked bluntly.

He peered up at me through his glasses. “I don’t know,” he said. “But you’re intelligent... and you’re outside it all. A man must: have somebody to tell to when things are getting too much for him.” He turned his head back to the sea again, hunching it into the fur collar of his topcoat. “Howe told you I was dying.”

“We’re all doing that,” I said.

He grunted. “Of course. But we’re not usually given a time limit. The best man in Harley Street gives me a year at most. A year’s not long,” he said hoarsely. “And at any moment I may get another stroke, and that’ll finish me.” He suddenly laughed. It was a bitter, violent sound. “When you’re told that, it changes your approach to life. Things which seemed important before cease to be important. Others loom larger. When we reach the Southern Cross,” he said, “get to know my son. I want your opinion of him.” He turned abruptly then and went ponderously down the ladder to the deck below. I watched him go, wishing I’d been able to hold him just a little longer. There were questions I’d like to have asked him.

In the middle of our meal that night, the radio operator brought Bland a message. His heavy brows dragged down as he read it. Then he got to his feet. “A word with you, Craig,” he growled.

I followed him to his cabin. He closed the door and handed me the message. “Read that,” he said.

I took the message to the light. It read:

RIDE TO BLAND: MEN DEMANDING INQUIRY NORDAHL’S DEATH. ERIK BLAND HAS REJECTED DEMAND PLEASE CONFIRM REJECTION. MOOD OK TÖNSBERG MEN DANGEROUS. WHALE VERY SCARCE. POSITION 57 98 S; 34 62 W. PACK ICE HEAVY.

I handed the message back to him. “The damned fool!” he growled. “It’ll be all over the ship that he’s not happy about Erik’s decision. And Erik’s quite right to reject a demand like that. It’s a matter for the officers to decide.” He paced up and down for a moment, tugging at the lobe of his ear. “What worries me is that they should be demanding an inquiry at all. If the circumstances warranted an inquiry, then Erik should have ordered it right away, instead of waiting for the men to demand it. And I don’t like Eide’s use of the word ‘dangerous,’ “he added. “He wouldn’t use it unless the situation was bad.” He swung round on me. “What’s the earliest we can expect to reach the Southern Cross?”

“Eight days at least,” I answered.

He nodded gloomily. “A lot can happen in eight days.”

“What are you scared of?” I asked. “You’re not suggesting that the men would mutiny, are you? Presumably a factory ship comes under normal British maritime laws. It takes a lot to drive men to mutiny.”

“Of course I’m not suggesting they’d mutiny. But they can make things damned awkward without going as far as mutiny. In a four-month season everything has got to move with clocklike precision.” He began tugging at the lobe of his ear again. “Erik can’t handle a thing like this. He hasn’t the experience.”

“Then put somebody else in charge,” I suggested. “Captain Eide, for instance.”

He looked up at me quickly. His small eyes were narrowed. I could see the battle going on inside him — pride against prudence. “No,” he said. “No. He must learn to handle things himself.” He paced up and down. He didn’t say anything more.

I went up onto the bridge. The sea was a heaving mass in the dreary half light. The air was bitterly cold. I went into the wheelhouse and looked at the barometer.

“No good,” said the bearded Norwegian at the wheel. He was right. The glass was very low and still falling.

The door flung back and Judie entered. “The weather looks bad,” she said. Her face was pinched and cold.

“We’re getting into high latitudes,” I reminded her.

She nodded bleakly, then asked, “Was that message from Eide?”

“Yes,” I said.

“What did it say?”

I told her.

She turned and stared out through the window. She didn’t speak for some time, and when she did, she startled me by saying, “I feel scared.”

I stepped forward and took her hand. It was cold as ice. “It’s rotten for you,” I said. “But there’s no need for you to worry. Things will sort themselves out when we reach the Southern Cross.”

“I don’t know,” she said. “I feel as though that’s just the beginning.” She looked up at me. Her gray eyes were deeply troubled. “Walter knows something — knows something that we don’t know.” Her voice trembled. She was overwrought.

I didn’t say anything and we stood there for some time, quite silent. She didn’t attempt to withdraw her hand from mine. But there was no contact between us. Then suddenly she jerked her hand away, pulled a pack of cigarettes from her pocket and offered me one.

“Is this the farthest south you’ve ever been?” she asked, her voice controlled and a little abrupt.

“Yes,” I said, and raised my other hand to show I was still smoking. “But I’m not new to ice. When I was twenty I went on a university expedition to Southeast Greenland.”

The conversation languished there, so I said, “I suppose this is your first trip into the Antarctic?”

“No,” she replied. “Not my first. When I was eight years old my father brought me with him to South Georgia. My mother had just died and we had no home. Bernt was one of the skytters at Grytviken. I was there about two months. Then he sent me to friends in New Zealand. I was there a year, and then he took me back with him at the end of the next season.”

Читать дальше