Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

Evans Ogden, L. J., and B. J. Stutchbury (1997) “Fledgling Care and Male Parental Effort in the Hooded Warbler ( Wilsonia citrina ).” Canadian Journal of Zoology 75:576—81.

———(1994) “Hooded Warbler (Wilsonia citrina):” In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 110. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists’ Union.

Godard, R. (1993) “Tit for Tat Among Neighboring Hooded Warblers.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 33:45—50.

———(1986) “Long-Term Memory of Individual Neighbors in a Migratory Songbird.” Nature 350:228—29.

*Lynch, J. F., E. S. Morton, and M. E. Van der Voort (1985) “Habitat Segregation Between the Sexes of Wintering Hooded Warblers ( Wilsonia citrina ).” Auk 102:714—21.

*Morton, E. S. (1989) “Female Hooded Warbler Plumage Does Not Become More Male-Like With Age.” Wilson Bulletin 101:460—62.

*Niven, D. K. (1997) Personal communication.

*———(1993) “Male-Male Nesting Behavior in Hooded Warblers.” Wilson Bulletin 105:190—93.

Stutchbury, B. J. M. (1998) “Extra-Pair Mating Effort of Male Hooded Warblers, Wilsonia citrina .” Animal Behavior 55:553—61.

*———(1994) “Competition for Winter Territories in a Neotropical Migrant: The Role of Age, Sex, and Color.” Auk 111:63—69.

Stutchbury, B. J., and L. J. Evans Ogden (1996) “Fledgling Adoption in Hooded Warblers ( Wilsonia citrina ): Does Extrapair Paternity Play a Role?” Auk 113:218—20.

*Stutchbury, B. J., and J. S. Howlett (1995) “Does Male-Like Coloration of Female Hooded Warblers Increase Nest Predation?” Condor 97:559—64.

Stutchbury, B. J., J. M. Rhymer, and E. S. Morton (1994) “Extrapair Paternity in Hooded Warblers.” Behavioral Ecology 5:384—92.

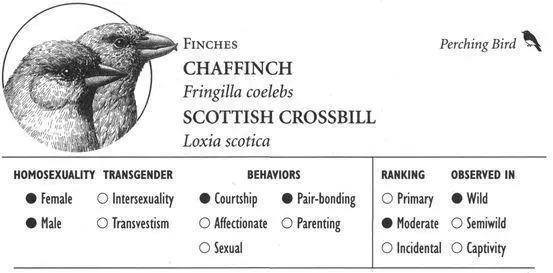

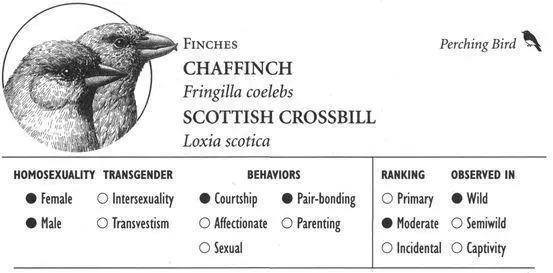

CHAFFINCH

IDENTIFICATION: A sparrow-sized bird with olive-brown plumage, distinctive white shoulder bars, and (in males) blue-gray crown. DISTRIBUTION: Europe, Siberia, central Asia, North Africa. HABITAT: Forest, farmland. STUDY AREAS: Ylivieska, Finland; near Cambridge, England; subspecies F.c. coelebs and F.c. gengleri.

SCOTTISH CROSSBILL

IDENTIFICATION: A sparrow-sized bird with olive to orange-red plumage and a distinctive crossed bill. DISTRIBUTION: Northern Scotland. HABITAT: Coniferous forest. STUDY AREAS: Speyside and Sutherland, Scotland.

Social Organization

Chaffinches and Scottish Crossbills commonly associate in flocks; the mating system involves (usually monogamous) pair-bonding.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Chaffinches sometimes form homosexual pair-bonds with each other. In this species, usually only males sing; however, in same-sex pairs, one female partner typically sings much in the manner of a male, throwing back her head while perched conspicuously in the trees (this is probably how she attracts her female mate). Her song resembles that of males in duration, loudness, and structure, consisting of a long stream of rapidly trilled notes of descending pitch, finished off with a staccato end phrase or “flourish.” It differs from male song, however, in having not quite as ringing a tone. Like male Chaffinches, she may even COUNTERSING in response to a neighboring male’s song, the two birds “replying” to each other with alternating or syncopated song phrases. Females in same-sex pairs may also try to sing together, although one partner may only be able to produce an incomplete version of the song. The two females behave like other mated couples, and may even engage in courtship pursuits known as SEXUAL CHASES. In this activity—which is a demonstration of sexual interest—one female zigzags after her partner using a special form of flying known as MOTH FLIGHT (rapid, shallow wingbeats without the pauses or undulating quality typical of regular flight). Occasionally, juvenile males pursue other males in such sexual chases.

Homosexual couples also occur in Scottish Crossbills—but among males. A male attracts potential mates by singing high in a treetop, advertising his presence with a loud stream of notes transcribed as chip-chip-chip-gee-gee-gee chip-chip-chip. Most singing males respond aggressively to other males who enter their territory, but occasionally the displaying male does not chase away another male that is attracted to him. The two males may then pair up and associate in much the same way that heterosexual couples do, except that copulation has not been observed between male partners. They synchronize their movements, traveling together between forest clumps, sometimes one leading the other. Occasionally, two neighboring males who are each heterosexually mated become companions. The two forage together and jointly defend clumps of pine trees (their principal food source) while still maintaining their opposite-sex bonds. The two males may even visit their female mates together, attending first to one and then the other, with one male feeding his female partner while his male companion waits for him.

Frequency: In both of these species, homosexual pairs are probably only an occasional occurrence. Although no statistics concerning the incidence of same-sex pairing are available, in Chaffinches about 1 in 150 nests contains a SUPERNORMAL CLUTCH of 7–8 eggs. In many species such larger-than-average clutches are laid by female pairs, and this may also be true in Chaffinches (although their specific association with same-sex pairing has not yet been demonstrated).

Orientation: Individual Chaffinches or Scottish Crossbills who form same-sex associations have not been tracked throughout their entire lives to determine if they only pair with members of the same sex. However, since heterosexual pairs in these species are usually lifelong, it is not unlikely that homosexual pairs would be as well. In addition, some Scottish Crossbill males are bisexual, forming bonds with both males and females simultaneously.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

A variety of nonprocreative heterosexual behaviors are found in Chaffinches and Scottish Crossbills. Chaffinch couples sometimes copulate during incubation (i.e., after fertilization has occurred), and only 40–50 percent of all matings during the fertilizable period involve full genital contact. Some pairs may attempt to mate more than 200 times for each clutch of eggs they produce, as often as 4 times an hour. Mounts are often not completed for a variety of reasons: the male may slip off the female’s back or mount in a reversed head-to-tail position, or (more commonly) either partner may flee from the other out of fear or because of provocation from its mate. In fact, heterosexual courtship and mating in this species often entails a considerable amount of aggressive behavior between the sexes. Many birds do not participate in breeding at all: there are surplus flocks of single birds in many populations (males in Scottish Crossbills, both sexes in Chaffinches), as well as nonbreeding pairs in Scottish Crossbills. Interestingly, outside of the breeding season sexual segregation is also the rule. Males and female tend to migrate separately (wintering flocks are often same-sex), and females generally travel farther than males, often resulting in local populations with more males than females. In fact, this phenomenon has lent the Chaffinch its scientific name: coelebs means “bachelor” in Latin.

Читать дальше