In some populations, 3-8 percent of males form polygamous trios in which they bond and breed with two females simultaneously. If the two females share a nest, one may help care for the other’s nestlings if her own eggs do not hatch. Many populations also have large numbers of nonbreeding birds, sometimes called FLOATERS because they do not occupy their own territories and tend to travel widely. As many as a quarter of all reproductively mature females are floaters. In addition to helping raise unrelated birds of their own species, Tree Swallows sometimes “adopt” nests belonging to other birds such as purple martins ( Progne subis ) or bluebirds ( Sialia spp.), raising the foster young in addition to their own. More than half of all Tree Swallow heterosexual pairs do not remain together for more than one breeding season. Single parenting also occasionally occurs in this species, for example if one parent is killed or dies during the breeding season. Frequently, however, the widowed parent re-pairs with another mate. If a single parent is laying or incubating eggs, its new mate often adopts the brood, but if a single parent already has nestlings from the previous mate, the new partner often kills them (usually by pecking) in order to begin breeding himself or herself. Infanticide also sometimes occurs when a female kills a paired female’s nestlings in order to try to precipitate a divorce and mate with her partner.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

Barber, C. A., R. J. Robertson, and P. T. Boag (1996) “The High Frequency of Extra-Pair Paternity in Tree Swallows Is Not an Artifact of Nestboxes.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 38:425-30.

Chek, A. A., and R. J. Robertson (1991) “Infanticide in Female Tree Swallows: A Role for Sexual Selection.” Condor 93:454-57.

Dunn, P. O., and R. J. Robertson (1992) “Geographic Variation in the Importance of Male Parental Care and Mating Systems in Tree Swallows.” Behavioral Ecology 3:291-99.

Dunn, P. O., and R. J. Robertson, D. Michaud-Freeman, and P. T. Boag (1994) “Extra-Pair Paternity in Tree Swallows: Why Do Females Mate with More than One Male?” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 35:273-81.

Leffelaar, D., and R. J. Robertson (1985) “Nest Usurpation and Female Competition for Breeding Opportunities by Tree Swallows.” Wilson Bulletin 97:221-24

———(1984) “Do Male Tree Swallows Guard Their Mates?” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 16:73-79.

Lifjeld, J. T., P. O. Dunn, R. J. Robertson, and P. T. Boag (1993) “Extra-Pair Paternity in Monogamous Tree Swallows.” Animal Behavior 45:213-29.

Lifjeld, J. T., and R. J. Robertson (1992) “Female Control of Extra-Pair Fertilization in Tree Swallows.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 31:89-96.

*Lombardo, M. P. (1996) Personal communication.

———(1988) “Evidence of Intraspecific Brood Parasitism in the Tree Swallow.” Wilson Bulletin 100:126–28.

———(1986) “Extrapair Copulations in the Tree Swallow.” Wilson Bulletin 98:150-52.

*Lombardo, M. P., R. M. Bosman, C. A. Faro, S. G. Houtteman, and T.S. Kluisza (1994) “Homosexual Copulations by Male Tree Swallows.” Wilson Bulletin 106:555-57.

Morrill, S. B., and R. J. Robertson (1990) “Occurrence of Extra-Pair Copulation in the Tree Swallow ( Tachycineta bicolor ).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 26:291-96.

Quinney, T. E. (1983) “Tree Swallows Cross a Polygyny Threshold.” Auk 100:750-54.

Rendell, W. B. (1992) “Peculiar Behavior of a Subadult Female Tree Swallow.” Wilson Bulletin 104:756-59.

Robertson, R. J. (1990) “Tactics and Counter-Tactics of Sexually Selected Infanticide in Tree Swallows.” In J. Blondel, A. Gosler, J.-D. Lebreton, and R. McCleery, eds., Population Biology of Passerine Birds: An Integrated Approach , pp. 381-90. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Robertson, R. J., B. J. Stutchbury, and R. R. Cohen (1992) “Tree Swallow ( Tachycineta bicolor ).” In A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 11. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists’ Union.

Stutchbury, B. J., and R. J. Robertson (1987a) “Signaling Subordinate and Female Status: Two Hypotheses for the Adaptive Significance of Subadult Plumage in Female Tree Swallows.” Auk 104:717-23.

———(1987b) “Behavioral Tactics of Subadult Female Floaters in the Tree Swallow.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 20:413-19.

———(1987c) “Two Methods of Sexing Adult Tree Swallows Before They Begin Breeding.” Journal of Field Ornithology 58:236-42.

———(1985) “Floating Populations of Female Tree Swallows.” Auk 102:651-54.

Venier, L. A., P. O. Dunn, J. T. Lifjeld, and R. J. Robertson (1993) “Behavioral Patterns of Extra-Pair Copulation in Tree Swallows.” Animal Behavior 45:412-15.

Venier, L. A., and R. J. Robertson (1991) “Copulation Behavior of the Tree Swallow, Tachycineta bicolor: Paternity Assurance in the Presence of Sperm Competition.” Animal Behavior 42:939-48.

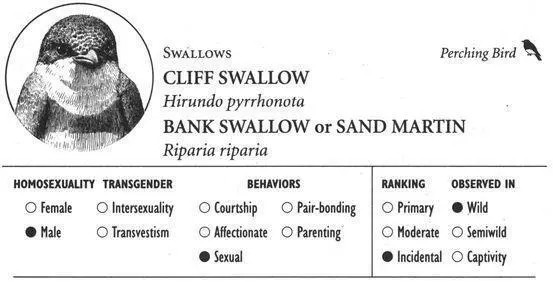

CLIFF SWALLOW

IDENTIFICATION: A bluish brown swallow with pale underparts, buff forehead, and a chestnut throat; tail is not forked. DISTRIBUTION: North and Central America; winters in southern South America. HABITAT: Open country, cliffs. STUDY AREAS: Near Jackson Hole (Moran), Wyoming, Lakeview, Kansas, and along the North and South Platte Rivers, Nebraska; subspecies H.p. hypopolia and H.p. pyrrhonota.

BANK SWALLOW

IDENTIFICATION: A small, sparrow-sized swallow with a slightly forked tail, brown plumage, white underparts, and a brown breast band. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout North America and Eurasia; winters to South America and southern Africa. HABITAT: Open country near water. STUDY AREAS: Near Madison, Wisconsin, and Dunblane, Scotland; subspecies R.r. riparia.

Social Organization

Cliff and Bank Swallows are highly gregarious and may flock by the hundreds or even thousands. They generally form mated pairs (although many alternative arrangements also occur, see below) and nest in colonies. Cliff Swallow colonies are the largest of any swallow in the world, often containing a thousand nests (and sometimes up to three times this number).

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Cliff and Bank Swallows often try to copulate with both males and females that are not their own mates. Unlike in Tree Swallows, these are usually forced copulations or “rapes,” since the bird being pursued—whether male or female—does not welcome the sexual advances of the male. Homosexual copulation attempts in Cliff Swallows take place on the ground at social gatherings of birds that are sunning themselves or gathering mud or grass for nests. Anywhere from a handful to several hundred individuals may be present at a time, although such groups usually contain 10-30 birds. At mud-gathering sessions, one male pounces on another male from above, landing on his back and often grabbing his head or neck feathers in his beak. At sunning sites, the male usually lands a few inches away from the other bird and makes threatening HEAD-FORWARD displays prior to jumping on his back. Once mounted, he spreads his tail and moves it sideways, trying to make cloacal (genital) contact, all the while vigorously flapping his wings; the other male usually strongly resists, and sometimes a fight ensues, before both birds fly off. The entire copulation attempt is usually quite brief, though it can last for up to 10 seconds (a relatively long duration for bird mountings). Forcible mountings of females follow this same pattern. When on the ground at mud-gathering sites, birds of both sexes typically flutter their wings above their backs to try to prevent males from mounting them.

Читать дальше