Male Bank Swallows also pursue both females and males to try to copulate with them. Males first make many INVESTIGATORY CHASES of unfamiliar birds to determine if they are worth following. If they find a bird they are interested in—which may be another male—a full-fledged SEXUAL CHASE ensues, sometimes drawing several birds into the pursuit as well. Often the targeted bird is able to get away, but sometimes the chase ends with a forced copulation attempt. Homosexual mountings also occur when birds congregate on the ground, for instance to gather nest materials or dust themselves. At times, a veritable “orgy” develops as numerous males frantically try to mount birds of both sexes. Sometimes one or two males will even mount a third male who is already copulating with another bird.

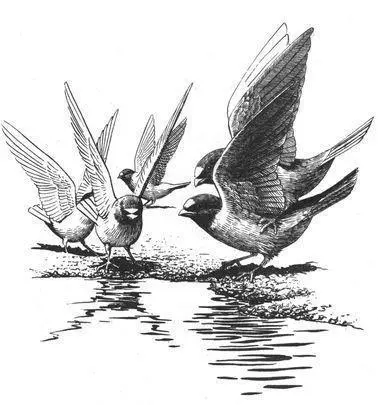

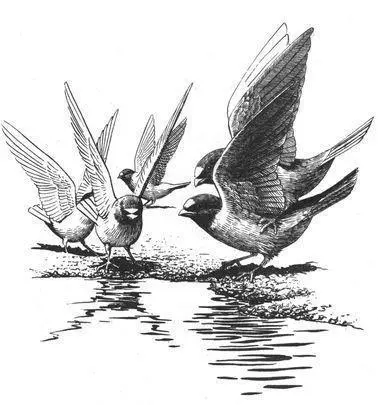

A male Cliff Swallow mounting another male (right) and attempting to copulate with him during a mud-gathering session

Frequency: In Bank Swallows, 8 percent of sexual chases are homosexual, while 36-40 percent of investigatory chases involve males pursuing other males. Cliff Swallow rape attempts are extremely common, occurring every two to three minutes at some mud-gathering sites; one male may attempt to mount six to eight different birds in a five-to-ten-minute period. These mounts are probably fairly evenly distributed between males and females, although homosexual mounts may in fact occur more often. When presented with stuffed birds of both sexes in identical poses, male Cliff Swallows mounted other males nearly 65 percent of the time.

Orientation: Most, if not all, male Cliff and Bank Swallows that pursue copulations with other males also try to forcibly mount females, and to this extent they are bisexual. However, in Cliff Swallows only a few males appear to engage in such behavior with either males or females. Many of these are unpaired birds, although males who are already heterosexually paired (including fathers) also sometimes participate in promiscuous copulations.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Heterosexual social life in Cliff and Bank Swallows is replete with behaviors that deviate from the monogamous-pair/nuclear-family model. As discussed above, a large proportion of heterosexually mated Swallows seek copulations with birds other than their partner, and considerable evidence suggests that these mounting attempts are nonprocreative. Because of the resistance of the bird being mounted, the copulation is often not completed and sperm is rarely transferred. In addition, such attempts may also occur outside the breeding season when there is no possibility of fertilization. Genetic studies have shown that probably only 2-6 percent of Cliff Swallow nests have young that might result from nonmonogamous sexual activity. However, nearly a quarter of all nestlings, in more than half of all nests, are raised by birds other than their biological mother and/or father. This is because Cliff Swallows participate in an extraordinary array of activities that serve to exchange eggs and nestlings between families. For example, as many as 43 percent of all nests contain an egg laid by an outside female—this bird usually has her own nest, but she also PARASITIZES or adds eggs to other nests (and often has eggs added to her own as well). In some cases, this female may even return to the foreign nest to incubate the entire clutch (even though only one egg is hers), but she does not help raise the nestlings once they hatch. Often the intruding female’s mate will destroy or toss out eggs in the host nest to make room for their own (up to 20 percent of all nests may suffer egg destruction). In other cases, males appear to destroy eggs in other nests so as to keep the laying female sexually receptive, thereby increasing the opportunities for heterosexual nonmonogamous matings. Birds also occasionally physically carry eggs from their own nest to another—about 6 percent of all nests contain eggs transferred this way. Finally, in a few cases Swallows have even been seen transferring actual baby birds between nests. Infanticide may also occur when birds attack and toss nestlings out of neighbors’ nests. In both species, young birds gather into large CRÈCHES or “day-care centers”—sometimes containing up to a thousand youngsters—which give them protection while their parents are away searching for food.

Divorce and single parenting also occur in Bank Swallows: females sometimes desert their mates to start a new family with another male, forcing their first mate to raise the nestlings on his own. In addition to the rape attempts described above, there is considerable aggression between the sexes as well. Ironically, male Bank Swallows often become violent toward their own female partners when trying to protect them from the advances of other males. Sometimes they knock their mate to the ground, fighting her directly, or try to force her back into their burrow. Nonreproductive sexual behaviors are also prevalent in these two species. Besides copulations outside the breeding season and group sexual activity (mentioned above), members of a Cliff Swallow pair often copulate at a rate far in excess of that needed simply to fertilize their eggs. In addition, males of both species have occasionally been seen trying to mate with dead birds, as well as with other species such as barn swallows ( Hirundo rustica ) and Tree Swallows.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Barlow, J. C., E. E. Klaas, and J. L. Lenz (1963) “Sunning of Bank Swallows and Cliff Swallows.” Condor 65:438-48.

Beecher, M. D., and 1. M. Beecher (1979) “Sociobiology of Bank Swallows: Reproductive Strategy of the Male.” Science 205:1282-85.

Beecher, M. D., I. M. Beecher, and S. Lumpkin (1981) “Parent-Offspring Recognition in Bank Swallows ( Riparia riparia ): I. Natural History.” Animal Behavior 29:86-94.

Brewster, W. (1898) “Revival of the Sexual Passion in Birds in Autumn.” Auk 15:194-95.

*Brown, C. R., and M.B. Brown (1996) Coloniality in the Cliff Swallow: The Effect of Group Size on Social Behavior . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

*———(1995) “Cliff Swallow ( Hirundo pyrrhonota ).” In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century , no. 149. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists’ Union.

———(1989) “Behavioral Dynamics of Intraspecific Brood Parasitism in Colonial Cliff Swallows.” Animal Behavior 37:777-96.

———(1988a) “A New Form of Reproductive Parasitism in Cliff Swallows.” Nature 331:66-68.

———(1988b) “The Costs and Benefits of Egg Destruction by Conspecifics in Colonial Cliff Swallows.” Auk 105:737-48.

———(1988c) “Genetic Evidence of Multiple Parentage in Broods of Cliff Swallows.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 23:379-87.

Butler, R. W. (1982) “Wing-fluttering by Mud-gathering Cliff Swallows: Avoidance of ‘Rape’ Attempts?” Auk 99:758-61.

*Carr, D. (1968) “Behavior of Sand Martins on the Ground.” British Birds 61:416-17.

Cowley, E. (1983) “Multi-Brooding and Mate Infidelity in the Sand Martin.” Bird Study 30:1-7.

*Emlen, J. T., Jr. (1954) “Territory, Nest Building, and Pair Formation in Cliff Swallows.” Auk 71:16-35.

———(1952) “Social Behavior in Nesting Cliff Swallows.” Condor 54:177-99.

Читать дальше