Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Barclay, R. M. R., and D. W. Thomas (1979) “Copulation Call of Myotis lucifugus: A Discrete Situation-Specific Communication Signal.” Journal of Mammalogy 60:632–34.

*Courts, S. E. (1996) “An Ethogram of Captive Livingstone’s Fruit Bats Pteropus livingstonii in a New Enclosure at Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust.” Dodo 32:15–37.

DeNault, L. K., and D. A. McFarlane (1995) “Reciprocal Altruism Between Male Vampire Bats, Desmodus rotundus. ” Animal Behavior 49:855–56.

*Greenhall, A. M. (1965) “Notes on the Behavior of Captive Vampire Bats.” Mammalia 29:441–51.

Martin, L., J. H. Kennedy, L. Little, H. C. Luckhoff, G. M. O’Brien, C. S. T. Pow, P. A. Towers, A. K. Waldon, and D. Y. Wang (1995) “The Reproductive Biology of Australian Flying-Foxes (Genus Pteropus ).” In P. A. Racey and S. M. Swift, eds., Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior of Bats, pp. 167–84. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

*Nelson, J. E. (1965) “Behavior of Australian Pteropodidae (Megachiroptera).” Animal Behavior 13:544–57.

*———(1964) “Vocal Communication in Australian Flying Foxes (Pteropodidae; Megachiroptera).” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 21:857–70.

*Neuweiler, V. G. (1969) “Verhaltensbeobachtungen an einer indischen Flughundkolonie ( Pteropus g. giganteus Briinn) [Behavioral Observations on a Colony of Indian Fruit-Bats].” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 26:166–99.

*Rollinat, R., and E. Trouessart (1896) “Sur la reproduction des chauves-souris [On the Reproduction of Bats].” Mémoires de la Societe Zoologique de France 9:214-40.

*———(1895) “Deuxième note sur la reproduction des Chiropteres [Second Note on the Reproduction of the Chiroptera].” Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances et Mémoires de la Société de Biologie 47:534–36.

Schmidt, C. (1988) “Reproduction.” In A. M. Greenhall and U. Schmidt, eds., Natural History of Vampire Bats, pp. 99–109. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press.

*Thomas, D. W., M. B. Fenton, and R. M. R. Barclay (1979) “Social Behavior of the Little Brown Bat, Myotis lucifugus. I. Mating Behavior. II. Vocal Communication.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 6:129–46.

Trewhella, W. J., P. F. Reason, J. G. Davies, and S. Wray (1995) “Observations on the Timing of Reproduction in the Congeneric Comoro Island Fruit Bats, Pteropus livingstonii and P. seychellensis comorensis. ” Journal of Zoology, London 236:327–31.

Turner, D. C. (1975) The Vampire Bat: A Field Study in Behavior and Ecology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

*Vesey-Fitzgerald, B. (1949) British Bats. London: Methuen.

Wilkinson, G. S. (1988) “Social Organization and Behavior.” In A. M. Greenhall and U. Schmidt, eds., Natural History of Vampire Bats, pp. 85–97. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press.

*———(1985) “The Social Organization of the Common Vampire Bat. I. Pattern and Cause of Association. II. Mating System, Genetic Structure, and Relatedness.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 17:111–34.

———(1984) “Reciprocal Food Sharing in the Vampire Bat.” Nature 308:181–84.

Waterfowl and Other Aquatic Birds

IDENTIFICATION: A dark gray goose with fine silvery-white feather patterning; the wild ancestor of domestic geese. DISTRIBUTION: Northern and central Eurasia, from Iceland to northeast China. HABITAT: Variable, including marshes, swamps, lakes, lagoons. STUDY AREAS: Konrad-Lorenz Institute, Grünau, Austria; Max-Planck Institute, Seewiesen, Germany; Wörlitzer Park, Dessau, Germany; subspecies A.a. anser, the Western Greylag Goose.

Social Organization

Greylag Geese usually associate in flocks containing a complex mixture of pairs, families with offspring, single birds, and subgroups of juveniles. Following the breeding season, migratory flocks sometimes contain thousands of birds. The mating system generally involves long-term, monogamous pair-bonding.

Description

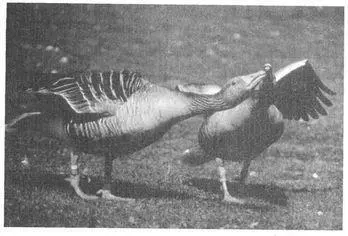

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual pairs made up of two ganders are a prominent form of pair-bonding in Greylag Geese. Male couples are stable and long-lasting: some have been documented as persisting for more than fifteen years, and most homosexual pairs (like heterosexual ones) are probably lifelong partnerships (Greylag Geese can live to be more than 20 years old). “Widower” ganders may even exhibit signs of “grief,” becoming despondent and defenseless upon the loss of their male partner. Most heterosexual pairs are also lifelong (and partners grieve the loss of their mates), but in many cases gander pairs are actually more closely bonded than male-female pairs, due in part to the intensity of their displays. One of these is the TRIUMPH CEREMONY, a pair-bonding behavior in which the two partners approach each other with extended necks and spread wings while making loud gabbling calls. Gander pairs spend significantly more time in this activity than do heterosexual pairs. They are also generally more vocal than male-female pairs—they often utter PRESSED CACKLING calls (rapid syllables produced with a high-pressure airstream) together in a cheek-to-cheek position and may even perform extended duets with ROLLING calls (deeper and louder notes).

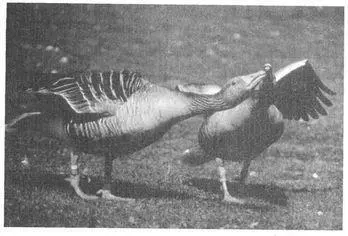

Two pair-bonded male Greylag Geese performing the “triumph ceremony”

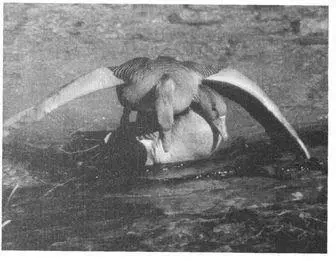

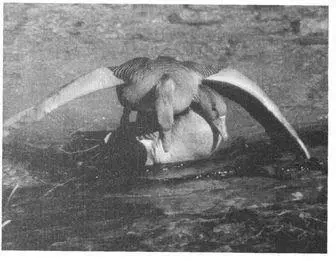

Paired ganders also sometimes engage in courtship and sexual behavior with one another. Pair-bonding is often initiated with the BENT-NECK DISPLAY, in which one male approaches and follows another with a distinct “kink” in his neck, his bill pointing downward. As a prelude to mating, both males perform aquatic displays such as NECK-DIPPING or NECK-ARCHING, in which the head is dipped below the surface while the neck is held in an elegant curve, its feathers ruffled to reveal their distinctive patterning. Following these displays, one male may mount the other as in heterosexual copulation. If there is a size difference between the two males, often the larger male mounts the smaller one. If the two ganders are equal in size, either bird may mount the other, and they often exchange positions when they copulate on different days. Following mating, the male who mounted his partner performs a display in which he lifts his head up and arches his folded wings almost vertically above his back. Sometimes, during homosexual activity one male may “masturbate” by mounting a log or some other object (a common form of masturbation in birds). In addition, a third bird—either male or female—occasionally joins a homosexual pair in their courtship activities, and may even be mounted by one of the ganders. In all cases, though, the concluding display takes place between the members of the male pair rather than with the third bird. Some gander pairs do not regularly engage in full mounting behavior, in part because both males prefer to mount each other without either one permitting himself to be mounted.

A Greylag gander mounting his male partner

Gander pairs often assume a powerful, high-ranking position within their flock, owing to their superior strength and courage. They are notably more aggressive than heterosexual pairs, frequently threatening, charging, chasing, and jointly attacking predators as well as other geese (especially unpaired males) and often appear to “terrorize” other birds. Paradoxically, each individual gander in a homosexual pair is significantly less aggressive than a male in a heterosexual pair—it is their combined strength that gives the couple its advantage. Homosexual pairs also differ from heterosexual ones in spending significantly more time on the periphery of the flock or away from it, especially during the spring breeding season. This, combined with the gander pair’s greater vigilance behavior (as well as the pair’s aggressiveness), has led some researchers to suggest that homosexual pairs may act as “guardians” for the flock as a whole. Sometimes a female is attracted to a gander pair—perhaps because of their strength and high standing—and tries to establish a bond with one or both of them. Often the males simply ignore such a female, but in some cases she is allowed to join them to form a trio. When this happens, one or both ganders may copulate with the female, although their homosexual bond usually remains primary. The trio may raise a family together, with the two ganders often searching for a nest site together and jointly defending their eggs and goslings. Occasionally, three ganders bond with each other as a same-sex trio, which may also later be joined by a female to form a “quartet”; again, goslings can be raised by all four birds together.

Читать дальше