Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As noted above, a large proportion of the male population in Zebras, as well as in Takhi, are nonbreeding bachelors. Some female Zebras also join the bachelor herds and do not participate in heterosexual activity while there (they remain for just under a year, on average). Wild equids also engage in an assortment of nonprocreative heterosexual activities. Males of all three species sometimes perform heterosexual mounts without an erection or penetration, while Takhi mares sometimes REVERSE mount stallions. Male Mountain Zebras and Takhi also frequently masturbate by erecting the penis and flipping it against the belly. Female equids sometimes also engage in an activity known as CLITORAL WINKING as part of courtship, in which the clitoris is rhythmically erected and wetted against the labia (often in conjunction with urination). Mountain Zebras occasionally participate in incestuous copulations: both father-daughter and brother-sister matings have been documented, although generally such pairings are avoided because females leave their family’s herd before they reach sexual maturity. In addition, male Plains Zebras often try to mate with unrelated juvenile females that are not yet sexually mature. In fact, stallions—alone or in groups of up to 18 at a time—may “abduct” adolescent females by separating and chasing them from their family groups, after which they will try to copulate with the young mares. Interestingly, the female shows the behavioral signs of being “in heat” before she reaches the age when she can actually conceive; usually an “abducted” mare returns to her family group after her period of “heat” is finished. In contrast, in Takhi it is often the females who behave aggressively toward males (as mentioned above).

In these equids, a number of violent behaviors are also directed toward young foals. Mountain Zebra and Takhi stallions occasionally kill foals; in the latter species, infanticide occurs when the male grabs the youngster by its neck, shaking it and tossing it into the air. Female Mountain Zebras also sometimes accidentally kill their foals by kicking them; ironically, this may occur when they are trying to defend them from other mares, who are often aggressive toward unrelated foals. However, in a few cases females have adopted an unrelated foal, and in one instance a female even rejected her own offspring and adopted another. A Plains Zebra mare may also allow another mare’s foal to suckle from her. Although Takhi males are not as involved in parenting as mares, a stallion may act as a “surrogate mother” to his own foal if it has lost its mother, even allowing the foal to “suckle” on his penis sheath.

Sources

asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Boyd, L. E. (1991) “The Behavior of Przewalski’s Horses and Its Importance to Their Management.” Applied Animal Behavior Science 29:301–18.

*———(1986) “Behavior Problems of Equids in Zoos.” In S. L. Crowell-Davis and K. A. Houpt, eds., Behavior, pp. 653–64. The Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice 2(3). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

*Boyd, L. E. and K. A. Houpt (1994) “Activity Patterns.” In L. Boyd and K. A. Houpt, eds., Przewalski’s Horse: The History and Biology of an Endangered Species, pp. 195–227. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Houpt, K. A., and L. Boyd (1994) “Social Behavior.” In L. Boyd and K. A. Houpt, eds. Przewalski’s Horse: The History and Biology of an Endangered Species, pp. 229–54. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Klingel, H. (1990) “Horses.” In Grzimek’s Encyclopedia of Mammals, vol. 4, pp. 557-94. New York: McGraw-Hill.

———(1969) “Reproduction in the Plains Zebra, Equus burchelli boehmi: Behavior and Ecological Factors.” Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, suppl. 6:339-45.

Lloyd, P. H., and D. A. Harper (1980) “A Case of Adoption and Rejection of Foals in Cape Mountain Zebra, Equus zebra zebra.” South African Journal of Wildlife Research 10:61–62.

Lloyd, P. H., and O. A. E. Rasa (1989) “Status, Reproductive Success, and Fitness in Cape Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra zebra).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 25:411–20.

*McDonnell, S. M., and J. C. S. Haviland (1995) “Agonistic Ethogram of the Equid Bachelor Band.” Applied Animal Behavior Science 43:147-88.

Monfort, S. L., N. P. Arthur, and D. E. Wildt (1994) “Reproduction in the Przewalski’s Horse.” In L. Boyd and K. A. Houpt, eds., Przewalski’s Horse: The History and Biology of an Endangered Species, pp. 173-93. Albany: State University of New York Press.

*Penzhorn, B. L. (1984) “A Long-term Study of Social Organization and Behavior of Cape Mountain Zebras Equus zebra zebra.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 64:97–146.

Rasa, O. A. E., and P. H. Lloyd (1994) “Incest Avoidance and Attainment of Dominance by Females in a Cape Mountain Zebra ( Equus zebra zebra ) Population.” Behavior 128:169-88.

Ryder, O. A., and R. Massena (1988) “A Case of Male Infanticide in Equus przewalskii. ” Applied Animal Behavior Science 21:187–90.

*Schilder, M. B. H. (1988) “Dominance Relationships Between Adult Plains Zebra Stallions in Semi-Captivity.” Behavior 104:300–319.

Schilder, M. B. H., and P. J. Boer (1987) “Ethological Investigations on a Herd of Plains Zebra in a Safari Park: Time-Budgets, Reproduction, and Food Competition.” Applied Animal Behavior Science 18:45–56.

van Dierendonck, M. C., N. Bandi, D. Batdorj, S. Dügerlham, and B. Munkhtsag (1996) “Behavioral Observations of Reintroduced Takhi or Przewalski Horses ( Equus ferus przewalskii ) in Mongolia.” Applied Animal Behavior Science 50:95–114.

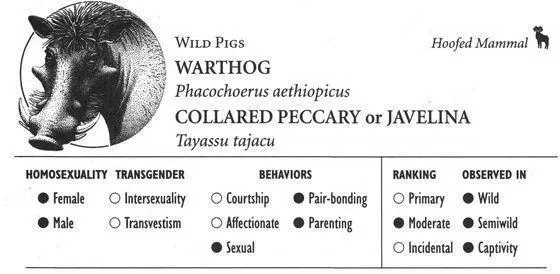

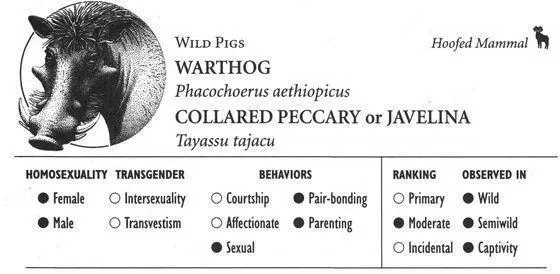

WARTHOG

IDENTIFICATION: A 3–5-foot-long wild pig with a large head, prominent tusks, and distinctive warts in front of the eyes and on the jaw. DISTRIBUTION: Sub-Saharan Africa. HABITAT: Steppe, savanna. STUDY AREA: Andries Vosloo Kudu Reserve, South Africa.

COLLARED PECCARY

IDENTIFICATION: A piglike mammal with grayish, speckled, or salt-and-pepper fur and a light-colored collar. DISTRIBUTION: Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, southward to northern Argentina. HABITAT: Varied, including desert, woodland, rain forest. STUDY AREAS: In the Tucson Mountains and near Tucson, Arizona; University of Arizona; National Institute of Agronomic Research, French Guiana; subspecies T.t. sonoriensis.

Social Organization

Warthogs tend to associate in matriarchal groups (also known as SOUNDERS) of several females and their offspring, and in all-male “bachelor” groups. Only 3 percent of groups contain both males and females, and many Warthog males are solitary. Males join female groups only briefly for mating, which is usually promiscuous—both males and females copulate with multiple partners—and the only long-lasting bonds that form are between animals of the same sex, primarily females. Collared Peccaries live in herds of 5–15 individuals, containing animals of both sexes.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual mounting occurs in both Collared Peccaries and Warthogs. In Collared Peccaries, females in heat often RIDE or mount other females, and males occasionally mount one another as well. In Warthogs, homosexual mounting also takes place among females in heat, though it is less common. Sometimes a female Warthog will mount another female from the side, a position that is also occasionally used in heterosexual mounting. Warthog females often develop long-lasting bonds with each other, and same-sex mounting can be a part of these pairings (stable male-female pairs do not occur in this species). The two females associate together for many years and may even jointly raise their young, combining their litters and suckling each other’s offspring. In addition, when one female is injured or temporarily unable to look after her young, the other female will take over parental duties. One such pair was seen consistently chasing away males who tried to get close to them. Biologists studying Warthogs call these pairs or groups of adult females without any males or offspring SPINSTER groups—they typically contain an older female with a younger one. Some of these pairings involve related females, such as sisters or mother and daughter—in which case some same-sex mounting may be incestuous—although nonrelated pairings also occur. Occasionally two male Warthogs pair off as well, though no sexual behavior has been observed between them.

Читать дальше