*———(1992) “Search or Relax: The Case of Bachelor Wood Bison.” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 31:195–203.

Krasinska, M., and Z. A. Krasiński (1995) “Composition, Group Size, and Spatial Distribution of European Bison Bulls in Bialowieza Forest.” Acta Theriologica 40:1–21.

*Krasiński, Z., and J. Raczyński (1967) “The Reproduction Biology of European Bison Living in Reserves and in Freedom.” Acta Theriologica 12:407-44.

*Lott, D. F. (1996–7) Personal communication.

*———(1983) “The Buller Syndrome in American Bison Bulls.” Applied Animal Ethology 11:183–86.

———(1981) “Sexual Behavior and Intersexual Strategies in American Bison (Bison bison ).” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 56:115–27.

*———(1974) “Sexual and Aggressive Behavior of Adult Male American Bison (Bison bison).” In V. Geist and E Walther, eds., Behavior in Ungulates and Its Relation to Management, vol. 1, pp. 382–94. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

*Lott, D. F., K. Benirschke, J. N. McDonald, C. Stormont, and T. Nett (1993) “Physical and Behavioral Findings in a Pseudohermaphrodite American Bison.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 29: 360–63.

*McHugh, T. (1972) The Time of the Buffalo. New York: Knopf.

*———(1958) “Social Behavior of the American Buffalo (Bison bison bison ).” Zoologica 43:1–40.

*Mloszewski, M. J. (1983) The Behavior and Ecology of the African Buffalo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

*Reinhardt, V. (1987) “The Social Behavior of North American Bison.” International Zoo News 203:3–8.

*———(1985) “Social Behavior in a Confined Bison Herd.” Behavior 92:209–26.

*Roe, F. G. (1970) The North American Buffalo: A Critical Study of the Species in Its Wild State. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

*Rothstein, A., and J. G. Griswold (1991) “Age and Sex Preferences for Social Partners by Juvenile Bison Bulls.” Animal Behavior 41:227–37.

*Sinclair, A. R. E. (1977) The African Buffalo: A Study of Resource Limitation of Populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

*Tulloch, D. G. (1979) “The Water Buffalo, Bubalus bubalis, in Australia: Reproductive and Parent-Offspring Behavior.” Australian Wildlife Research 6:265–87.

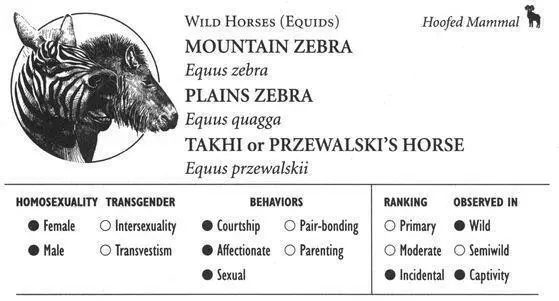

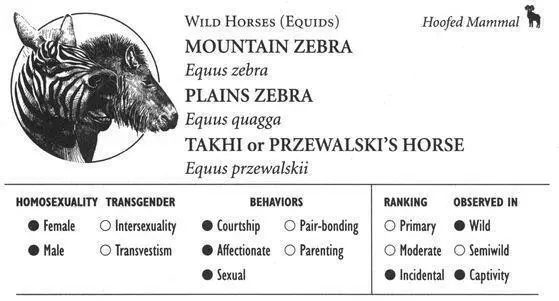

MOUNTAIN, PLAINS ZEBRAS

IDENTIFICATION: The familiar wild horse with a black-and-white-striped pattern; Mountain Zebras usually have a distinctive dewlap. DISTRIBUTION: Southern and eastern Africa; Mountain species is endangered. HABITAT: Mountainous slopes and plateaus; grassland, desert, semidesert. STUDY AREAS: Mountain Zebra National Park, South Africa, subspecies E.z. zebra, the Cape Mountain Zebra; Burgers Zoo, the Netherlands, subspecies E.q. chapman, Chapman’s Zebra, and E.q. boehmi, Grant’s Zebra.

TAKHI

IDENTIFICATION: The wild ancestor of domestic horses; coat usually tan or chestnut colored, with an erect mane, black tail and lower legs, white muzzle, and thin black stripe along back and several on upper forelegs. DISTRIBUTION: Formerly in central Asia (Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Sinkiang, Transbaikal); now extinct in the wild. HABITAT: Steppes. STUDY AREA: Bronx Zoo, New York.

Social Organization

Mountain and Plains Zebras have two main social units: breeding groups containing a herd stallion and three to five females with their offspring, and nonbreeding or “bachelor” groups. Groups combine to form herds numbering in the tens of thousands in Plains Zebras. Little is known of Takhi social organization in the wild, where the species is extinct (although it is beginning to be reintroduced from cap-418 tive populations). It is likely that they have a system similar to that of Mountain and Plains Zebras, including both bachelor and “harem” herds.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Mounting between male Mountain Zebras is prefaced by a special ritualized display or “greeting” ceremony performed by two herd stallions, combining elements of courtship and sexual behaviors similar to those in heterosexual interactions. When two herd stallions meet, they approach each other with a stiff, high-stepping walk, holding their heads erect and ears forward as a friendly gesture. The males then rub first their noses and then their bodies together. Body rubbing is done either with the stallions facing in the same direction, or with one male’s head at the other’s rump. In the latter position, one male may nuzzle and sniff the other’s genitals with his muzzle. Finally, one stallion sometimes mounts the other, or they may take turns mounting each other; occasionally a male will walk a few steps while another stallion is mounted on him. Plains Zebra males have also been observed placing their head on the rump of another male, a ritualized movement (also found in heterosexual courtship) that is thought to indicate an intention to mount the other male. When a herd stallion meets a bachelor male, many of the same behaviors occur, except for mounting. In addition, the bachelor male displays a distinctive facial expression resembling that used by Zebra mares in heat—lowering the head and pulling the lips and mouth corners back to expose the teeth—combined with a high-pitched call. Bachelor males also “greet” each other this way, often leading to play-fighting in which the males gently bite at each other and rear up on their hind legs. Bachelor males also sometimes mount each other as part of play-fighting.

Takhi mares occasionally mount each other; in some cases, pregnant females perform this sexual behavior with other females. Mares may mount each other from a sideways position in addition to from behind (the usual position for heterosexual mounting, although younger males also sometimes use a lateral mounting position). Such females may be among the highest-ranking mares in the herd and can also be noticeably aggressive toward males, kicking or biting them when the latter try to court other females.

Frequency: In captivity, mounting and attempted mounting occur in about 60 percent of interactions between male Plains Zebras. Among wild Mountain Zebras, homosexual interactions are less frequent. About 20 percent of play interactions between bachelor males involve mounting, while herd stallions associate with bachelor males (including “greetings” interactions) about 5 percent of the time. Female homosexual mounting in Takhi occurs occasionally (in captivity).

Orientation: In Zebras, herd stallions that engage in homosexual mounting and courtshiplike “greeting” behavior with other males also court and mate with females. Bachelor males, on the other hand, are exclusively homosexual to the extent that they engage in such behaviors, since they do not generally participate in heterosexual activity while in the bachelor herds. A little more than half of the male population of Mountain Zebras consists of bachelor males; most males join bachelor herds when they are just under two years old and stay for an average of two and a half years. About half of all bachelor males go on to become herd stallions and therefore are sequentially bisexual. However, some males remain in the bachelor herds for their entire lives, never mating heterosexually. Among Takhi, at least some females that mount other females are functionally bisexual, since they may be pregnant when they engage in homosexual activity.

Читать дальше