Wiigh-Masak and I stand in silence beside the grave of the unknown livestock, as though paying our respects. It’s dark now and hard to see the plant, though it appears to be doing well. I tell Wiigh-Masak that I think it’s great, this quest for an ecologically sound, meaningful memorial. I tell her I’m rooting for her, then quickly rephrase the sentiment, omitting gardening-related verbs.

And I am. I hope Wiigh-Masak succeeds, and I hope WR2 succeeds. I’m all for choices, in death as in life. Wiigh-Masak is encouraged by my support, as she has been by the support of the Church of Sweden and her corporate backers and the people who have responded positively in the polls. “It was and is,” she confides as the wind shimmies the leaves on the cow’s memorial shrub, “very important to feel I’m not crazy.”

12. REMAINS OF THE AUTHOR

Will She or Won’t She?

It has long been a tradition among anatomy professors to donate their bodies to medical science. Hugh Patterson, the UCSF professor whose lab I visited, looks at it this way: “I’ve enjoyed teaching anatomy, and look, I get to do it after I die.” He told me he felt like he was cheating death.

According to Patterson, the venerable anatomy teachers of Renaissance Padua and Bologna, as death sidled near, would choose their best student and ask him to prepare their skull as an anatomical exhibit. (Should you one day visit Padua, you can see some of these skulls, at the university medical school.)

I don’t teach anatomy, but I understand the impulse. Some months back, I gave thought to becoming a skeleton in a medical school classroom.

Years ago I read a Ray Bradbury story about a man who becomes obsessed with his skeleton. He has come to think of it as a sentient, sinister entity that lives inside him, biding its time until he dies and the bones slowly prevail. I began thinking about my skeleton, this solid, beautiful thing inside me that I would never see. I didn’t see it becoming my usurper, but more my stand-in, my means to earthly immortality. I’ve enjoyed hanging around in rooms doing nothing much, and look, I get to do it after I die . Plus, on the off chance that an afterlife exists, and that it includes the option of home planet visitations, I’d be able to pop by the med school and finally see what my bones looked like. I liked the idea that when I was gone, my skeleton would live on in some sunny, boisterous anatomy classroom. I wanted to be a mystery in some future medical student’s head: Who was this woman? What did she do? How did she come to be here?

Of course, the mystery could as easily be engendered by a more routine donation of my remains. Upward of 80 percent of the bodies left to science are used for anatomy lab dissections. Most assuredly, a lab cadaver occupies the thoughts and dreams of its dissectors. The problem, for me, is that while a skeleton is ageless and aesthetically pleasing, an eighty-year-old corpse is withered and dead. The thought of young people gazing in horror and repulsion at my sagging flesh and atrophied limbs does not hold strong appeal. I’m forty-three, and already they’re doing it. A skeleton seemed the less humiliating course.

I actually went so far as to contact a facility at the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology that accepts bodies specifically to harvest the bones. I told the woman who runs it about my book and said that I wanted to come see how skeletons are made. In the Bradbury story, the protagonist ends up having his bones pulled out through his mouth, by an alien disguised as a beautiful woman. Though he was reduced to a jellyfish heap on his living-room floor, his body remained intact. No blood was spilled.

This was, of course, not the case at the Maxwell lab. I was told I would have the choice of observing one of two steps: a “cut-down” or a “pour-off.” The cut-down was more or less what it sounded like. They got the bones out the only way—barring retractable and highly specialized alien mouthparts—one can: by cutting away the flesh and muscle that surrounds them. Residual meat and sinew is dissolved by boiling the bones in a solution for a few weeks, periodically pouring off the broth and replacing the solution. I pictured the young men of Padua tending to their beloved professors’ heads as they simmered and bobbed. I pictured the actors in a Shakespearean theater troupe I read about last year, confronted by a dead cast member’s last request that his skull be used as Yorick. People really need to think these requests through.

About a month later, I got another e-mail from the university. They were writing to tell me they had switched to an insect-based process, wherein fly larvae and carnivorous beetles perform their own scaled-down, drawn-out version of the cut-down.

I did not sign on to become a skeleton. For one thing, I don’t live in New Mexico and they won’t come pick you up. Also, it turns out that the university doesn’t make skeletons, only bones. The bones are left unarticulated and added to the university’s osteological collection. [44] If you live nearby, by all means donate. The Maxwell Museum holds the world’s only collection of contemporary—within the last fifteen years—human bones, used to study everything from forensics to the skeletal manifestations of diseases. P.S.:Your family can go in and visit your bones, which the staff will lay out for you, though probably not in the shape of an all-together skeleton.

No one in this country, I learned, is making skeletons for medical schools.

The vast majority of the world’s medical school skeletons have, over the years, been imported from Calcutta. No longer. According to a June 15,1986, Chicago Tribune story, India banned the export of bones in 1985, after reports surfaced of children being kidnapped and murdered for their bones and skulls. According to one story, which I desperately hope is exaggerated, fifteen hundred children per month were being killed in the state of Bihar, their bones then sent to Calcutta for processing and export. Since the ban, the supply of human bones has dwindled to almost nothing. Some come out of Asia, where, it is rumored, they are dug up from Chinese cemeteries and stolen from Cambodia’s killing fields. They are old, mossy, and generally of poor quality, and for the most part, detailed plastic skeletons have taken their place. So much for my future as a skeleton.

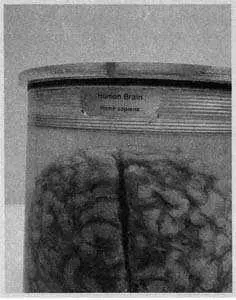

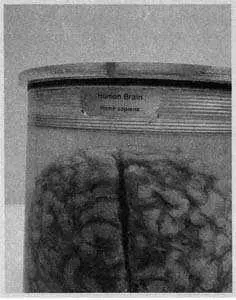

For similarly dumb and narcissistic reasons, I also once considered spending eternity at the Harvard Brain Bank. I wrote about it in my Salon.com column, which was disappointing for the Brain Bank’s director, who assumed I would be writing a serious article about the facility’s serious and very worthwhile research pursuits. Here is an abridged version of the column:

There are many good reasons to become a brain donor.

One of the best is to advance the study of mental dysfunction. Researchers cannot study animal brains to learn about mental illness because animals don’t get mentally ill. While some animals—cats, for example, and dogs small enough to fit into bicycle baskets—seem to incorporate mental illness as a natural personality feature, animals are not known to have diagnosable brain disorders like Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia. So researchers need to study brains of mentally ill humans and, as controls, brains of normal humans like you and me (okay, you).

My reasons for becoming a donor aren’t very good at all. My reasons boil down to a Harvard Brain Bank donor wallet card, which enables me to say “I’m going to Harvard” and not be lying. You do not need brains to go to the Harvard Brain Bank, only a brain.

Читать дальше