Mary Roach

STIFF

The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers

The way I see it, being dead is not terribly far off from being on a cruise ship. Most of your time is spent lying on your back. The brain has shut down. The flesh begins to soften. Nothing much new happens, and nothing is expected of you.

If I were to take a cruise, I would prefer that it be one of those research cruises, where the passengers, while still spending much of the day lying on their backs with blank minds, also get to help out with a scientist’s research project. These cruises take their passengers to unknown, unimagined places. They give them the chance to do things they would not otherwise get to do.

I guess I feel the same way about being a corpse. Why lie around on your back when you can do something interesting and new, something useful ?

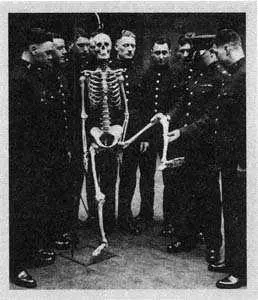

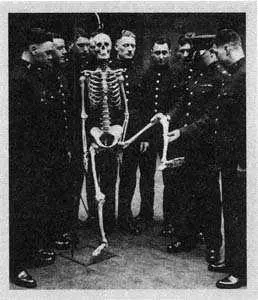

For every surgical procedure developed, from heart transplants to gender reassignment surgery, cadavers have been there alongside the surgeons, making history in their own quiet, sundered way. For two thousand years, cadavers—some willingly, some unwittingly—have been involved in science’s boldest strides and weirdest undertakings. Cadavers were around to help test France’s first guillotine, the “humane” alternative to hanging. They were there at the labs of Lenin’s embalmers, helping test the latest techniques. They’ve been there (on paper) at Congressional hearings, helping make the case for mandatory seat belts. They’ve ridden the Space Shuttle (okay, pieces of them), helped a graduate student in Tennessee debunk spontaneous human combustion, been crucified in a Parisian laboratory to test the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin.

In exchange for their experiences, these cadavers agree to a sizable amount of gore. They are dismembered, cut open, rearranged. But here’s the thing: They don’t endure anything. Cadavers are our superheros: They brave fire without flinching, withstand falls from tall buildings and head-on car crashes into walls. You can fire a gun at them or run a speedboat over their legs, and it will not faze them. Their heads can be removed with no deleterious effect. They can be in six places at once. I take the Superman point of view: What a shame to waste these powers, to not use them for the betterment of humankind.

This is a book about notable achievements made while dead. There are people long forgotten for their contributions while alive, but immortalized in the pages of books and journals. On my wall is a calendar from the Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The photograph for October is of a piece of human skin, marked up with arrows and tears; it was used by surgeons to figure out whether an incision would be less likely to tear if it ran lengthwise or crosswise. To me, ending up an exhibit in the Mütter Museum or a skeleton in a medical school classroom is like donating money for a park bench after you’re gone: a nice thing to do, a little hit of immortality. This is a book about the sometimes odd, often shocking, always compelling things cadavers have done.

Not that there’s anything wrong with just lying around on your back. In its way, rotting is interesting too, as we will see. It’s just that there are other ways to spend your time as a cadaver. Get involved with science.

Be an art exhibit. Become part of a tree. Some options for you to think about.

Death. It doesn’t have to be boring.

There are those who will disagree with me, who feel that to do anything other than bury or cremate the dead is disrespectful. That includes, I suspect, writing about them. Many people will find this book disrespectful. There is nothing amusing about being dead, they will say.

Ah, but there is. Being dead is absurd. It’s the silliest situation you’ll find yourself in. Your limbs are floppy and uncooperative. Your mouth hangs open. Being dead is unsightly and stinky and embarrassing, and there’s not a damn thing to be done about it.

This book is not about death as in dying. Death, as in dying, is sad and profound. There is nothing funny about losing someone you love, or about being the person about to be lost. This book is about the already dead, the anonymous, behind-the-scenes dead. The cadavers I have seen were not depressing or heart-wrenching or repulsive. They seemed sweet and well-intentioned, sometimes sad, occasionally amusing. Some were beautiful, some monsters. Some wore sweatpants and some were naked, some in pieces, others whole.

All were strangers to me. I would not want to watch an experiment, no matter how interesting or important, that involved the remains of someone I knew and loved. (There are a few who do. Ronn Wade, who runs the anatomical gifts program at the University of Maryland at Baltimore, told me that some years back a woman whose husband had willed his body to the university asked if she could watch the dissection. Wade gently said no.) I feel this way not because what I would be watching is disrespectful, or wrong, but because I could not, emotionally, separate that cadaver from the person it recently was. One’s own dead are more than cadavers, they are place holders for the living. They are a focus, a receptacle, for emotions that no longer have one. The dead of science are always strangers. [1] Or almost always. Every now and then, it will happen that an anatomy student recognizes a lab cadaver. “I’ve had it happen twice in a quarter of a century,” says Hugh Patterson, an anatomy professor at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical School.

Let me tell you about my first cadaver. I was thirty-six, and it was eighty-one. It was my mother’s. I notice here that I used the possessive “my mother’s,” as if to say the cadaver that belonged to my mother, not the cadaver that was my mother. My mom was never a cadaver; no person ever is. You are a person and then you cease to be a person, and a cadaver takes your place. My mother was gone. The cadaver was her hull. Or that was how it seemed to me.

It was a warm September morning. The funeral home had told me and my brother Rip to show up there about an hour before the church service.

We thought there were papers to fill out. The mortician ushered us into a large, dim, hushed room with heavy drapes and too much air-conditioning. There was a coffin at one end, but this seemed normal enough, for a mortuary. My brother and I stood there awkwardly. The mortician cleared his throat and looked toward the coffin. I suppose we should have recognized it, as we’d picked it out and paid for it the day before, but we didn’t. Finally the man walked over and gestured at it, bowing slightly, in the manner of a maître d’ showing diners to their table. There, just beyond his open palm, was our mother’s face. I wasn’t expecting it. We hadn’t requested a viewing, and the memorial service was closed-coffin. We got it anyway. They’d shampooed and waved her hair and made up her face. They’d done a great job, but I felt taken, as if we’d asked for the basic carwash and they’d gone ahead and detailed her.

Hey, I wanted to say, we didn’t order this. But of course I said nothing. Death makes us helplessly polite.

The mortician told us we had an hour with her, and quietly retreated. Rip looked at me. An hour ? What do you do with a dead person for an hour?

Mom had been sick for a long time; we’d done our grieving and crying and saying goodbye. It was like being served a slice of pie you didn’t want to eat. We felt it would be rude to leave, after all the trouble they’d gone to. We walked up to the coffin for a closer look. I placed my palm on her forehead, partly as a gesture of tenderness, partly to see what a dead person felt like. Her skin was cold the way metal is cold, or glass.

Читать дальше