The beast that excreted it was a Shasta ground sloth. Today, the only surviving sloths are two tree-dwelling species found in the Central and South American tropics, small and light enough to quietly inhabit rain forest canopies far from the ground, out of harm’s way. This one, however, was the size of a cow. It walked on its knuckles like another of its surviving relatives, the giant South American anteater, to protect the claws it used to forage and to defend itself. It weighed half a ton, yet it was the smallest of the five sloth species that lumbered around North America, from the Yukon to Florida. The Florida variety, the size of a modern elephant, topped three tons. That was only half the size of a ground sloth in Argentina and Uruguay, which at 13,000 pounds stood taller than the largest mammoth.

A decade would pass before Paul Martin got to visit the opening in the red Grand Canyon sandstone wall above the Colorado River where his first sloth dung ball had been collected. By then, extinct American ground sloths had come to mean much more to him than simply more oversized mammals that had mysteriously toppled into oblivion. The fate of sloths would provide what Martin believed was conclusive proof of a theory forming in his mind as data accumulated like layers of stratified sediment. Inside Rampart Cave was a mound of dung deposited, he and his colleagues concluded, by untold generations of female sloths who took shelter there to give birth. The manure pile was five feet high, 10 feet across, and more than 100 feet long. Martin felt like he’d entered a sacred place.

When vandals set it on fire 10 years later, the fossil dung heap was so enormous that it burned for months. Martin mourned, but by then he had been setting blazes of his own in the paleontology world with his theory of what had wiped out millions of ground sloths, wild pigs, camels, Proboscidea, multiple species of horses—at least 70 entire genera of large mammals throughout the New World, all vanished in a geologic twinkling of about 1,000 years:

“It’s pretty simple. When people got out of Africa and Asia and reached other parts of the world, all hell broke loose.”

Martin’s theory, soon dubbed the Blitzkrieg by its supporters and detractors alike, contended that, starting with Australia about 48,000 years ago, as humans arrived on each new continent they encountered animals that had no reason to suspect that this runty biped was particularly threatening. Too late, they learned otherwise. Even when hominids were still Homo erectus, they had already been mass-producing axes and cleavers in Stone Age factories, such as the one at Olorgesailie, Kenya, discovered a million years later by Mary Leakey. By the time a group of them arrived at the threshold of America 13,000 years ago, they had been Homo sapiens for at least 50,000 years. Using their bigger brains, humans by then had mastered not just the technology of attaching fluted stone points to wooden shafts, but also the atlatl, a handheld wooden lever that enabled them to propel a spear fast and precisely enough to fell dangerously large animals from a relatively safe distance.

The first Americans, Martin believes, were the ones who expertly produced the leaf-shaped flint projectile points found widely throughout North America. Both the people and their lithic points are known as Clovis, named for the New Mexico site where they were first discovered. Radiocarbon dates of organic matter found in Clovis sites have sharpened past estimates, and archaeologists now agree that Clovis people were in America 13,325 years ago. What exactly their presence signifies is, however, still a matter for hot dispute, beginning with Paul Martin’s premise that humans perpetrated the extinctions that killed off three-fourths of America’s late Pleistocene megafauna, a menagerie far richer than Africa’s today.

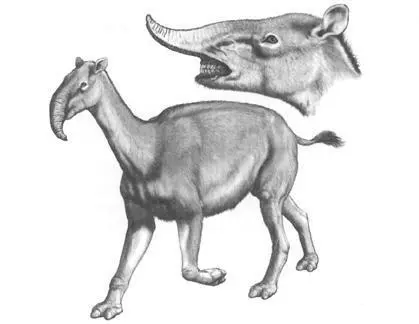

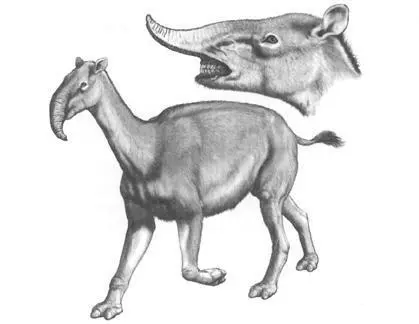

Key to Martin’s Blitzkrieg theory is that in at least 14 of those sites, Clovis points were found with mammoth or mastodon skeletons, some stuck between their ribs. “If Homo sapiens had never evolved,” he says, “North America would have three times as many animals over one ton as Africa today.” He ticks off Africa’s current five: “Hippos, elephants, giraffes, two rhinoceroses. We’d have 15. Even more, when we add South America. There were amazing mammals down there. Litopterns that looked like a camel with nostrils on top of their nose rather than on the tip. Or toxodons, one-ton brutes like a cross between a rhino and hippo, but anatomically neither.”

Litoptern. Macrauchenia patachonica.

ILLUSTRATION BY CARL BUELL.

All these existed, the fossil record shows, but not everyone agrees on what happened to them. One challenge to Paul Martin’s theory questions whether Clovis people were actually the first humans to enter the New World. Among the objectors are Native Americans wary of any suggestion that they immigrated, which would undermine their indigenous status; they denounce the idea that their origins trace to a Bering land bridge as an attack on their faith. Even some archaeologists question whether a Bering ice-free corridor really existed, and suggest that the first Americans actually arrived by water, skirting the ice sheet to continue down the Pacific coast. If boats reached Australia from Asia nearly 40 millennia earlier, why not boats between Asia and America?

Still others point to a handful of archaeological sites that supposedly predate Clovis. Archaeologists who excavated the most famous of these, Monte Verde, in southern Chile, believe that humans may have settled there twice: once 1,000 years prior to Clovis, the other time 30,000 years ago. If so, at that time the Bering Strait would likely not have been dry land, meaning an ocean voyage from some direction was involved. Even the Atlantic has been suggested, by archaeologists who think that Clovis techniques for flaking chert resemble paleolithics that developed in France and Spain 10,000 years earlier.

Questions about the validity of Monte Verde’s radiocarbon dates soon cast doubt over initial claims that it proved early human presence in the Americas. Matters were further muddied when most of the peat bog that had preserved Monte Verde’s poles, stakes, spear points, and knotted grasses was bulldozed before other archaeologists could examine the excavation site.

Even if early humans did somehow find their way to Chile before Clovis, argues Paul Martin, their impact was brief, local, and ecologically negligible, like that of the Vikings who colonized Newfoundland before Columbus. “Where are the abundant tools, artifacts, and cave paintings that their contemporaries left all over Europe? Pre-Clovis Americans wouldn’t have met competing human cultures, like the Vikings did. Only animals. So why didn’t they spread?”

The second, more fundamental controversy about Martin’s Blitzkrieg theory, for years the most accepted explanation for the fate the of the New World’s big animals, asks how a few nomadic bands of hunter-gatherers could annihilate tens of millions of large animals. Fourteen kill sites on an entire continent hardly add up to megafaunal genocide.

Nearly half a century later, the debate Paul Martin ignited remains one of science’s greatest flash points. Careers have been built upon proving or attacking his conclusions, fueling a protracted, not-always-polite war waged by archaeologists, geologists, paleontologists, dendro- and radiochronologists, paleoecologists, and biologists. Nevertheless, nearly all are Martin’s friends, and many are his former students.

The leading alternatives they’ve proposed to his overkill theory involve either climate change or disease, and have inevitably come to be known as “over-chill” and “over-ill.” Over-chill, with the greatest number of adherents, is partly a misnomer, because both overheating and overcooling get blamed. In one argument, a sudden temperature reversal at the end of the Pleistocene, just as glaciers were melting away, plunged the world briefly back into the Ice Age and caught millions of vulnerable animals unaware. Others propose the opposite: that rising Holocene temperatures doomed furry species, because they had adapted over thousands of years to frigid conditions.

Читать дальше