Over-ill suggests that arriving humans, or creatures that accompanied them, introduced pathogens that nothing alive in the Americas had ever encountered. It may be possible to prove this by analyzing mammoth tissues that will likely be discovered as glaciers continue to thaw. The premise has a grim analog: Most descendants of whoever were the first Americans died horribly in the century following European contact. Only a tiny fraction lost their lives to the point of a Spanish sword; the rest succumbed to Old World germs for which they had no antibodies: smallpox, measles, typhoid, and whooping cough. In Mexico alone, where an estimated 25 million Meso-Americans lived when the Spaniards first appeared, only 1 million remained 100 years later.

Even if disease mutated from humans to mammoths and the other Pleistocene giants, or passed directly from their dogs or livestock, that would still put the blame on Homo sapiens. As for over-chill, Paul Martin replies: “To quote some paleo-climate experts, ‘Climate change is redundant.’ It’s not that the climate doesn’t change, but that it changes so often.”

Ancient European sites show that Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis both drifted north or south with advancing or receding ice sheets. Megafauna, Martin says, would have done the same. “Large animals are buffered against temperature by their size. And they can migrate long distances—maybe not as far as birds, but compared to a mouse, pretty well. Since mice, pack rats, and other small, warm-blooded creatures survived the Pleistocene extinctions,” he adds, “it’s hard to believe that a sudden climate shift made life intolerable for big mammals.”

Plants, even less mobile than animals, and generally more climatesensitive, also seem to have survived. Among the sloth dung in Rampart and other Grand Canyon caves, Martin and his colleagues encountered ancient pack rat middens layered with thousands of years of vegetation remains. With the possible exception of a single variety of spruce, no species harvested by pack rat or sloth residents of these caves met temperatures extreme enough to spell their extinction.

But the clincher for Martin is the sloths. Within a millennium of the Clovis people’s appearance, every slow, plodding, easy target of a ground sloth was gone—on the continents of North and South America. Yet radiocarbon dates confirm that bones found in caves in Cuba, Haiti, and Puerto Rico belonged to ground sloths still alive 5,000 years later. Their ultimate disappearance coincided with the eventual arrival of humans in the Greater Antilles 8,000 years ago. In the Lesser Antilles, on islands that humans reached even later, like Grenada, the sloth remains are even younger.

“If a change in climate was powerful enough to exterminate ground sloths from Alaska to Patagonia, you’d expect it would also take them out in the West Indies. But that didn’t happen.” This evidence also suggests that the first Americans arrived on the continent on foot, not as seafarers, since it took them five millennia to reach the Caribbean.

On another, far-distant island, is a further hint that, had humans never evolved, Pleistocene megafauna might be around today. During the Ice Age, Wrangel Island, a wedge of rocky tundra in the Arctic Ocean, was connected to Siberia. It was so far north, however, that humans entering Alaska missed it. As warming seas rose in the Holocene, Wrangel was again isolated from the mainland; its population of woolly mammoths, spared but now stranded, was forced to adapt to the limited resources of an island. During the span in which humans went from caves to building great civilizations in Sumer and Peru, Wrangel Island’s mammoths lived on, a dwarf species that lasted 7,000 years longer than mammoths on any continent. They were still alive 4,000 years ago, when Egyptian pharaohs ruled.

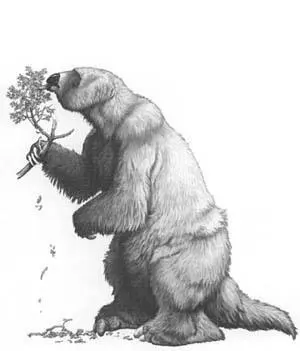

Giant ground sloth. Megatherium americanum.

ILLUSTRATION BY CARL BUELL.

More recent still was the extinction of one of the most astonishing of Pleistocene megafauna: the world’s biggest bird, which also lived on an island humans overlooked. New Zealand’s flightless moa, at 600 pounds, weighed twice as much an ostrich and stood nearly a yard taller. The first humans colonized New Zealand about two centuries before Columbus sailed to America. By the time he did, the last of 11 moa species was all but gone.

To Paul Martin, it’s obvious. “Big animals were the easiest to track. Killing them gave humans the most food, and the most prestige.” Within 100 miles of his Tumamoc Hill laboratory, past the Tucson jumble, are three of the 14 known Clovis kill sites. The richest of them, Murray Springs, strewn with Clovis spear points and dead mammoths, was found by two of Martin’s students, Vance Haynes and Peter Mehringer. Its eroded strata, wrote Haynes, resembled “pages in a book that record the last 50,000 years of Earth history.” Those pages contain obituaries of several extinct North American species: mammoth, horse, camel, lion, giant bison, and dire wolf. Adjacent sites add tapir, and two of the few megafauna that survive today: bear and bison.

Which raises a question: Why did they survive, if humans were slaughtering everything? Why does North America still have grizzlies, buffalo, elk, musk ox, moose, caribou, and puma, but not the other big mammals?

Polar bears, caribou, and musk ox inhabit regions where relatively few humans have ever lived—and those who did found fish and seals to be far easier prey. South of the tundra, where trees resume, live bears and mountain lions, furtive and fleet creatures adept at hiding in forests or among boulders. Others, like Homo sapiens, entered North America around the time that the Pleistocene species departed. Today’s plains buffalo are genetically closer to Poland’s wisent than to the now-extinct giant bison that were killed at Murray Springs. After the giant bison were gone, the plains buffalo population exploded. Likewise, today’s moose came from Eurasia after the American stag moose were extinguished.

Carnivores such as sabre-toothed tigers likely disappeared along with their prey. Some former Pleistocene residents—tapirs, peccaries, jaguars, and llamas—escaped farther south to forested refuges in Mexico, Central America, and beyond. Along with the die-off of the rest, this left huge niches to be filled, and eventually buffalo, elk, and company rushed in to fill them.

As Vance Haynes excavated Murray Springs, he found signs that drought had forced Pleistocene mammals to seek water—a cluster of footprints around one messy hole was clearly an attempt by mammoths to dig a well. There, they would have been easy pickings for hunters. In the layer just above the footprints is a band of black fossilized algae killed in a cold snap cited by many over-chill advocates—except, in paleontology’s equivalent of a smoking gun, the mammoth bones all lie below it, not within it.

Yet one more clue that, had humans never existed, the descendants of these slaughtered mammoths would likely be around today: when their big prey vanished, so did Clovis people and their famous lithic points. With game gone and weather turned cold, perhaps they moved south. But within a matter of years, the Holocene warmed, and successors to the Clovis culture appeared, their smaller spear points tailored to smaller plains bison. An equilibrium of sorts was reached between these “Folsom people” and those remaining animals.

Had these succeeding generations of Americans absorbed a lesson from the gluttony of their ancestors who killed Pleistocene herbivores as if the supply were endless—until it crashed? Perhaps, although the existence of much of the Great Plains themselves is due to fires set by their descendants, the American Indians, both to concentrate game that browse, such as deer, in forest patches, and to create grassland for grazers like buffalo.

Читать дальше