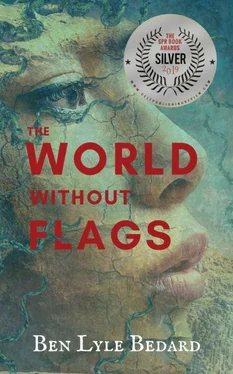

Ben Lyle Bedard

THE WORLD WITHOUT FLAGS

Icall myself Kestrel. This wasn’t always my name, but people are who they need to be. That’s the way the world is now. I don’t remember when it was different, what it was like before the Worm. I was young when it came and changed my life forever. It changed all of our lives, swooping down on us like some kind of judgement. There’s some people who think that it was our fault, the plague that came and reduced everything to ruins. The Worm came through the water we drank, wriggled up our veins to our brain and lodged in there. Then it grew in your brain and it took you over. They called them Zombies, but I don’t think they ate anyway or came back from the dead. It was just the word we had for that kind of thing. They got a high fever and started yearning for water and their eyes turned red and they cried blood. That’s how you knew they were going to die, if they started bleeding from their eyes. But they weren’t zombies. They were just sick people whose brains weren’t theirs anymore. Some of them broke under the pressure. We called them cracked. They went crazy and killed and if they so much as scratched you, you’d get the Worm too. I know most people died because of it. My parents died of it. Most everyone did. There’s people left, of course. We didn’t go extinct, obviously. But not too many of us are left.

No one has gotten the Worm for years and years. It went away with the world it destroyed. The older people who remember what it was like to live in cities and cars and televisions and all that stuff, they talk a lot about why the Worm happened and why it vanished. They won’t stop talking about it. For them, I guess, it’s like it happened just yesterday. But it was like ten years ago. Most of my life, really.

I don’t care as much about the reasons for the Worm as the older people do. I don’t think it would change anything if we knew why it happened. It wouldn’t bring back my mother or my father. The older people are more angry about the Worm than we are, us younger ones. Some older people say it was made by governments. Some say the Russians did it. Some say it was just some bug in the Amazon that wouldn’t have hurt anyone if we had left the rainforests alone. Truth is, no one knows much about it, just that it started in Brazil and came north. I’ve seen people kill over whose fault it was. But I’ve seen people killed for all sorts of things. It doesn’t mean anything, really. People kill each other. That’s what people do. That’s why you have to be careful. That’s why you have to think. That’s what Eric is always telling me. Think. So I changed my name to Kestrel so I sound a little more dangerous.

You are who you are to survive. You become who you have to be. You change. You adapt. I don’t know who I’ll be tomorrow.

I just know I’ll be who I have to be.

We call this place the Homestead. Except for winter, I like it here. The Homestead is just a patch of land south of the lakes. On the maps we have, we live in the State of Maine, but there’s no Maine anymore. That’s just a meaningless bunch of squiggles on a map now. On the Homestead, there’s a farmhouse with faded gray clapboards and two big barns where we keep all the animals. Around the farmhouse are the fields we work hard to clear and hoe and plow. At first there was only one field but over the years we cleared two more, one behind the farmhouse and another to the west. I still remember how hard that was. Our hands bled and our bodies were tight knots of pain. One of us, an old guy named Jim, he worked so hard, he just wasted away and died one day. He died right out there in the fields. I remember that quite a lot. How he just sank down on one knee and then fell to the side. By the time we got to him, he was dead. Thing was, when he died, his mouth opened wide and when he fell, it was like he was biting the earth. It was horrible. It didn’t look peaceful at all. That was back before we really understood what we were doing. We had some bad winters then. Better not to think too much about that or about Jim.

The Homestead has trees by the river and in the summer, the fields outside turn golden. There’s trout in the Rill and bigger trout in the lakes above. There’s deer all year round. A lot of deer. A few of us have learned to hunt them with bows. We have guns, but we save the bullets. Ammunition is hard to come by and we can’t waste it on deer. In the winter, it’s cold, but I have to admit that the snow is always so peaceful and calm and beautiful.

About five or six years ago, we started building log houses because the farmhouse got too small for everyone. We built them on the hill above the farm so we could have a good look toward the south. Over the years we’ve built ten houses and one lodge. We call it the Village. We should probably have a better name for it than that, but we don't have much time to sit around and wonder what to call a few houses on a hill.

We had to completely rebuild the first few houses we tried, but the new ones aren’t nearly as bad. We’ve learned a lot about how to build log houses, how to fill in the chinks, how to build on stone foundations, how to build so that when the cabin shrinks over time, which it will, the doors don’t get stuck. We still have a lot to learn though. Franky calls it “relearning” because people had this all figured out once, how to live without electricity, directly from the land. Franky likes that term, “relearning,” and he uses it whenever he can.

There’s 43 people in the Homestead, and I could name each one of them and tell you their stories. They come from all over this area, Boston, Portland, Quebec. A few of the children were born here. We even have a little cemetery, but there’s no bodies buried there, only ashes and a big boulder where we carve people’s names. After the Worm, we always burn our dead. We put all the ashes of our dead in the cemetery and the flowers that grow there are strong and bright and beautiful. We have a library. We have music and dances when we can. We play games. We ski in the winter, swim in the summer. We have guns and knives. We try to keep people safe. We try to keep each other alive.

I know I’m lucky to have a place I can call home. A lot of people don’t have that. They live wandering the world, scrambling to survive, scavenging for whatever the old world left behind like dogs in the garbage pile. They come sometimes to the Homestead to trade. They have metal and tools and toothpaste. A lot of plastic trash that we trade for anyway. Their eyes are hollow. They’d kill you just as soon as be your friend. You can tell by looking at them that they’ve lost something important. You have to learn how to see that in this world. You have to be smart with people.

Sometimes someone comes and we trust them and let them stay. We watch them very carefully, but usually they’re okay. They start working like everyone else, and they bring whatever skills they have to help us. These are the lucky ones, like me. I know I’m lucky to be here, to have these people at the Homestead who trust me with their lives and I trust them with mine, even the ones I don’t like much.

I’ve lived here most of my life. I could say I’ve lived here all my life because I don’t remember much before we came here, before the Worm. Sometimes I dream of a woman with long, wiry dark hair, hair that I loved to feel in my hand. In my dream, she’s singing, but I can’t hear her voice. It’s more like a feeling that she’s singing. And she’s holding me but I can’t feel her arms around me. All I can feel is her hair in my hands. And I have a feeling in my dream, a feeling I never have in life. It’s like being in warm water, suspended, floating, and everything is outside of me, beyond my grasp. I’m pretty sure the woman singing is my mother. That’s pretty much what’s left of my life before the Worm.

Читать дальше