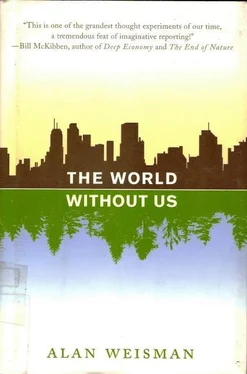

Alan Weisman

THE WORLD WITHOUT US

In memory of

Sonia Marguerite

with lasting love

from a world without you

Das Firmament blaut ewig, und die Erde

Wird lange fest steh’n und aufblüh’n im Lenz.

Du aber, Mensch, wie lange lebst denn du?

The firmament is blue forever, and die Earth

Will long stand firm and bloom in spring.

But, man, how long will you live?

—Li-Tai-Po/Hans Bethge/Gustav Mahler

The Chinese Flute: Drinking Song of the Sorrow of the Earth Das Lied von der Erde

PRELUDE

A Monkey Koan

ONE JUNE MORNING in 2004, Ana María Santi sat against a post beneath a large palm-thatched canopy, frowning as she watched a gathering of her people in Mazáraka, their hamlet on the Río Conambu, an Ecuadoran tributary of the upper Amazon. Except for Ana María’s hair, still thick and black after seven decades, everything about her recalled a dried legume pod. Her gray eyes resembled two pale fish trapped in the dark eddies of her face. In a patois of Quichua and a nearly vanished language, Zápara, she scolded her nieces and granddaughters. An hour past dawn, they and everyone in the village except Ana María were already drunk.

The occasion was a minga, the Amazonian equivalent of a barn raising. Forty barefoot Zápara Indians, several in face paint, sat jammed in a circle on log benches. To prime the men for going out to slash and burn the forest to clear a new cassava patch for Ana María’s brother, they were drinking chicha —gallons of it. Even the children slurped ceramic bowls full of the milky, sour beer brewed from cassava pulp, fermented with the saliva of Zápara women who chew wads of it all day. Two girls with grass braided in their hair passed among the throng, refilling chicha bowls and serving dishes of catfish gruel. To the elders and guests, they offered hunks of boiled meat, dark as chocolate. But Ana María Santi, the oldest person present, wasn’t having any.

Although the rest of the human race was already hurtling into a new millennium, the Zápara had barely entered the Stone Age. Like the spider monkeys from whom they believe themselves descended, the Zápara essentially still inhabit trees, lashing palm trunks together with bejuco vines to support roofs woven of palm fronds. Until cassava arrived, palm hearts were their main vegetable. For protein they netted fish and hunted tapirs, peccaries, wood-quail, and curassows with bamboo darts and blowguns.

They still do, but there is little game left. When Ana María’s grandparents were young, she says, the forest easily fed them, even though the Zápara were then one of the largest tribes of the Amazon, with some 200,000 members living in villages along all the neighboring rivers. Then something happened far away, and nothing in their world—or anybody’s—was ever the same.

What happened was that Henry Ford figured out how to mass-produce automobiles. The demand for inflatable tubes and tires soon found ambitious Europeans heading up every navigable Amazonian stream, claiming land with rubber trees and seizing laborers to tap them. In Ecuador, they were aided by highland Quichua Indians evangelized earlier by Spanish missionaries and happy to help chain the heathen, lowland Zápara men to trees and work them until they fell. Zápara women and girls, taken as breeders or sex slaves, were raped to death.

By the 1920s, rubber plantations in Southeast Asia had undermined the market for wild South American latex. The few hundred Zápara who had managed to hide during the rubber genocide stayed hidden. Some posed as Quichua, living among the enemies who now occupied their lands. Others escaped into Peru. Ecuador’s Zápara were officially considered extinct. Then, in 1999, after Peru and Ecuador resolved a long border dispute, a Peruvian Zápara shaman was found walking in the Ecuadoran jungle. He had come, he said, to finally meet his relatives.

The rediscovered Ecuadoran Zápara became an anthropological cause célèbre. The government recognized their territorial rights, albeit to only a shred of their ancestral land, and UNESCO bestowed a grant to revive their culture and save their language. By then, only four members of the tribe still spoke it, Ana María Santi among them. The forest they once knew was mostly gone: from the occupying Quichua they had learned to fell trees with steel machetes and burn the stumps to plant cassava. After a single harvest, each plot had to be fallowed for years; in every direction, the towering forest canopy had been replaced by spindly, second-growth shoots of laurel, magnolia, and copa palm. Cassava was now their mainstay, consumed all day in the form of chicha. The Zápara had survived into the 21st century, but they had entered it tipsy, and stayed that way.

They still hunted, but men now walked for days without finding tapirs or even quail. They had resorted to shooting spider monkeys, whose flesh was formerly taboo. Again, Ana María pushed away the bowl proffered by her granddaughters, which contained chocolate-colored meat with a tiny, thumbless paw jutting over its side. She raised her knotted chin toward the rejected boiled monkey.

“When we’re down to eating our ancestors,” she asked, “what is left?”

So far from the forests and savannas of our origins, few of us still sense a link to our animal forebears. That the Amazonian Zápara actually do is remarkable, since the divergence of humans from other primates occurred on another continent. Nevertheless, lately we have had a creeping sense of what Ana María means. Even if we’re not driven to cannibalism, might we, too, face terrible choices as we skulk toward the future?

A generation ago, humans eluded nuclear annihilation; with luck, we’ll continue to dodge that and other mass terrors. But now we often find ourselves asking whether inadvertently we’ve poisoned or parboiled the planet, ourselves included. We’ve also used and abused water and soil so that there’s a lot less of each, and trampled thousands of species that probably aren’t coming back. Our world, some respected voices warn, could one day degenerate into something resembling a vacant lot, where crows and rats scuttle among weeds, preying on each other. If it comes to that, at what point would things have gone so far that, for all our vaunted superior intelligence, we’re not among the hardy survivors?

The truth is, we don’t know. Any conjecture gets muddled by our obstinate reluctance to accept that the worst might actually occur. We may be undermined by our survival instincts, honed over eons to help us deny, defy, or ignore catastrophic portents lest they paralyze us with fright.

If those instincts dupe us into waiting until it’s too late, that’s bad. If they fortify our resistance in the face of mounting omens, that’s good. More than once, crazy, stubborn hope has inspired creative strokes that snatched people from ruin. So, let us try a creative experiment: Suppose that the worst has happened. Human extinction is a fait accompli. Not by nuclear calamity, asteroid collision, or anything ruinous enough to also wipe out most everything else, leaving whatever remained in some radically altered, reduced state. Nor by some grim eco-scenario in which we agonizingly fade, dragging many more species with us in the process.

Instead, picture a world from which we all suddenly vanished. Tomorrow.

Читать дальше