Only she thinks it’s something more. Genetics indicate that at some point 3 million to 5 million years ago, two populations of a species that was the common ancestor to these two monkeys became separated. Adjusting to distinct environments, they gradually diverged from each other. Through a similar situation involving finch populations that became isolated on various Galápagos islands, Charles Darwin first deduced how evolution works. In that case, 13 different finch species emerged in response to locally available food, their bills variously adapted to cracking seeds, eating insects, extracting cactus pulp, or even sucking the blood of seabirds.

In Gombe, the opposite has apparently occurred. At some point, as new forest filled the barrier that once divided these two species, they found themselves sharing a niche. But then they became marooned together, as the forest surrounding Gombe National Park gave way to cassava croplands. “As the number of available mates of their own species dwindled,” Detwiler figures, “these animals have been driven to desperate—or creative—survival measures.”

Her thesis is that hybridization between two species can be an evolutionary force, just like natural selection is within one. “Maybe at first the mixed offspring isn’t as fit as either parent,” she says. “But for whatever reason—constrained habitat, or low numbers—the experiment keeps getting repeated, until eventually a hybrid as viable as its parent emerges. Or, maybe even with advantage over the parents, because the habitat has changed.”

That would make the future offspring of these monkeys human artifacts: their parents forced together by agricultural Homo sapiens who so fragmented east Africa that populations of monkeys and other species like shrikes or flycatchers had to interbreed, crossbreed, perish—or do something very creative. Such as evolve.

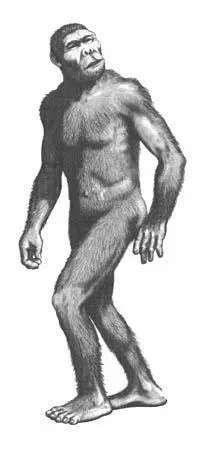

Something similar may have happened here before. Once, when its Rift was only beginning to form, Africa’s tropical forest filled the continent’s midriff from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic. Great apes had already made their appearance, including one that in many ways resembled chimpanzees. No remnants of it have ever been found, for the same reason that chimp remains are so rare: in tropical forests, heavy rains leach minerals from the ground before anything can fossilize, and bones decompose quickly. Yet scientists know it existed, because genetics show that we and chimps descended directly from the same ancestor. The American physical anthropologist Richard Wrangham has given this undiscovered ape a name: Pan prior.

Prior, that is, to Pan troglodytes, today’s chimpanzee, but also prior to a great dry spell that overtook Africa about 7 million years ago. Wetlands retreated, soils dried, lakes disappeared, and forests shrank into pocket refuges, separated by savannas. What caused this was an ice age advancing from the poles. With much of the world’s moisture locked into glaciers that buried Greenland, Scandinavia, Russia, and much of North America, Africa became parched. No ice sheets reached it, although glacial caps formed on volcanoes like Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya. But the climatic change that fragmented Africa’s forest, more than twice the size of today’s Amazon, was due to the same distant white juggernaut that was smashing conifers in its path.

That faraway ice sheet stranded populations of African mammals and birds in patches of forest where, over the next few million years, they evolved their separate ways. At least one of them, we know, was driven to try something daring: taking a stroll in a savanna.

If humans vanished, and if something eventually replaced us, would it begin as we did? In southwest Uganda, there’s a place where it’s possible to see our history reenacted in microcosm. Chambura Gorge is a narrow ravine that cuts for 10 miles through a deposit of dark brown volcanic ash on the floor of the Rift Valley. In startling contrast to the surrounding yellow plains, a green band of tropical sobu, ironwood, and leafflower trees fills this canyon along the Chambura River. For chimpanzees, this oasis is both a refuge and a crucible. Lush as it is, the gorge is barely 500 yards across, its available fruit too limited to satisfy all their dietary needs. So from time to time, brave ones risk climbing up the canopy and leaping to the rim, to the chancy realm of the ground.

With no ladder of branches to help them see over the oat and citronella grasses, they must raise themselves on two feet. Perched for a moment on the verge of being bipedal, they scan for lions and hyenas among the scattered fig trees on the savanna. They select a tree they calculate they can reach without becoming food themselves. Then, as we also once did, they run for it.

About 3 million years after distant glaciers pushed some courageous, hungry specimens of Pan prior out of forests no longer big enough to sustain us—and some of them proved imaginative enough to survive—the world warmed again. Ice retreated. Trees regained their former ground and then some, even covering Iceland. Forests reunited across Africa, again from the Atlantic shore to the Indian, but by then Pan prior had segued into something new: the first ape to prefer the grassy woodlands at the forest’s edge. After more than a million years of walking on two feet, its legs had lengthened and its opposable big toes had shortened. It was losing the ability to dwell in trees, but its sharpened survival skills on the ground had taught it to do so much more.

Now we were hominids. Somewhere along the way, as Australopithecus was begetting Homo, we learned not only to follow the fires that opened up savannas that we’d learned to inhabit, but how to make them ourselves. For some 3 million years more, we were too few to create more than local patchworks of grassland and forests whenever distant ice ages weren’t doing it for us. Yet in that time, long before Pan prior’s most recent descendant, surnamed sapiens, appeared, we must have become numerous enough to again try being pioneers.

Were the hominids who wandered out of Africa again intrepid risk-takers, their imaginations picturing even more bounty beyond the savanna’s horizon?

Or were they losers, temporarily out-competed by tribes of stronger blood cousins for the right to stay in our cradle?

Or were they simply going forth and multiplying, like any beast presented with rich resources, such as grasslands stretching all the way to Asia? As Darwin came to appreciate, it didn’t matter: when isolated groups from the same species proceed in their separate ways, the most successful among them learn to flourish in new surroundings. Exiles or adventurers, the ones who survived filled Asia Minor and then India. In Europe and Asia, they began to develop a skill long known to temperate creatures like squirrels but new to primates: planning, which required both memory and foresight to store food in seasons of plenty in order to outlast seasons of cold. A land bridge got them through much of Indonesia, but to reach New Guinea and, about 50,000 years ago, Australia, they had to learn to become seafarers. And then, 11,000 years ago, observant Homo sapiens in the Middle East figured out a secret until then known only to select species of insects: how to control food supplies not by destroying plants, but by nurturing them.

Australopithecus africanus.

ILLUSTRATION BY CARL BUELL.

Because we know the Middle Eastern origin of the wheat and barley they grew, which soon spread southward along the Nile, we can guess that—like shrewd Jacob returning with a cornucopia of gifts to win over his powerful brother, Esau—someone bearing seeds and the knowledge of agriculture returned from there to the African homeland. It was an auspicious time to do so, because yet another ice age—the last one—had once again stolen moisture from lands that glaciers didn’t reach, tightening food supplies. So much water was frozen into glaciers that the oceans were 300 feet lower than today.

Читать дальше