China’s impact on Africa has so far, it would appear, been positive. [1065] [1065] Interview with Jeffrey Sachs, ‘ Africa ’s Long Road Out of Poverty’, International Herald Tribune , 11 April 2007.

First, it has driven up both demand and prices for those many African countries that are commodity exporters, at least until the onset of the global downturn. Sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP increased by an average of 4.4 % in 2001-4, 5–6% in 2005-6, and a projected 7 % in 2007, compared with 2.6 % in 1999–2001, [1066] [1066] Marks, introduction in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa , p. 5.

with China clearly the major factor since it has accounted for most of the increase in the global consumption of commodities since 1998. [1067] [1067] Raphael Kaplinsky, ‘Winners and Losers: China ’s Trade Threats and Opportunities for Africa ’, in Wild and Mepham, The New Sinosphere , p. 16.

In addition, the growing availability of cheap Chinese manufactured goods has had a beneficial effect for consumers. [1068] [1068] Ibid., p. 18.

The losers have been those countries that are not commodity exporters or those producers — as in South Africa, Kenya and Mauritius, for instance — which compete with Chinese manufacturing exports. [1069] [1069] Ibid.

Chinese textile exports have led to many redundancies in various African nations, notably South Africa, Lesotho and Kenya. [1070] [1070] Alden, China in Africa , pp. 79–82.

Overall, however, there have been a lot more winners than losers. Second, China ’s arrival as an alternative source of trade, aid and investment has created a competitive environment for African states where they are no longer simply dependent on Western nations, the IMF and the World Bank. The most dramatic illustration of this has been Angola, which was able to break off negotiations with the IMF in 2007 when China offered it a loan on more favourable terms. [1071] [1071] Ibid., pp. 44, 68.

China ’s involvement thus has had the effect of boosting the strategic importance of Africa in the world economy. [1072] [1072] Rocha, ‘A New Frontier in the Exploitation of Africa’s Natural Resources’, p. 29.

Third, Chinese assistance tends to come in the form of a package, including important infrastructural projects like roads, railways and major public buildings, as well as the provision of technical expertise. [1073] [1073] Examples of public projects include the construction of an extension to the parliament building in Uganda, presidential palaces in Kinshasa and Harare, and new offices for the ministries of foreign affairs in Angola and Mozambique; Alden, China in Africa , p. 23.

(In contrast, most Western investment in Africa is concentrated in oil and other commodities and lacks the infrastructural dimension.) Fourth, Chinese aid has far fewer strings attached than that of Western nations and institutions. While the IMF and the World Bank have insisted, in accord with their ideological agenda, on the liberalization of foreign trade, privatization and a reduced role for the state, the Chinese stance is far less restrictive. [1074] [1074] Kaplinsky, ‘Winners and Losers’, pp. 12–13.

In addition, the West frequently attaches political conditions concerning democracy and human rights while the Chinese insist on no such conditionality. This conforms to the Chinese emphasis on respect for sovereignty, which they regard as the most important principle in international law and which is directly related to their own historical experience during the ‘century of humiliation’. In April 2006, in an address to the Nigerian National Assembly, Hu Jintao declared: ‘ China steadfastly supports the wish of the African countries to safeguard their independence and sovereignty and choose their roads of development according to their national conditions.’ [1075] [1075] Text of Chinese president’s speech to Nigerian General Assembly, 27 April 2006, posted on www.fmprc.gov.cn.

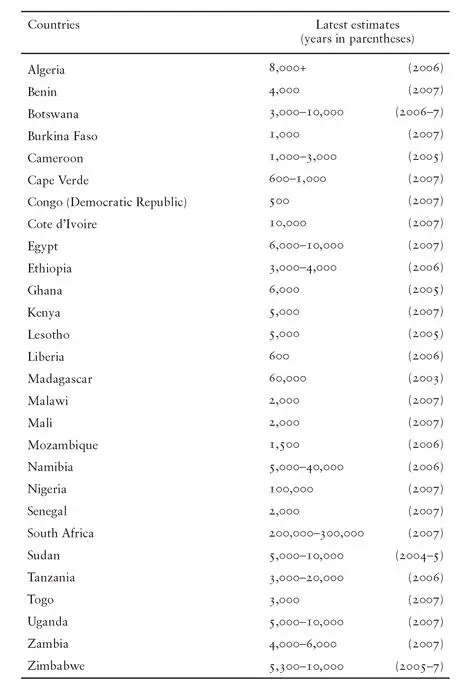

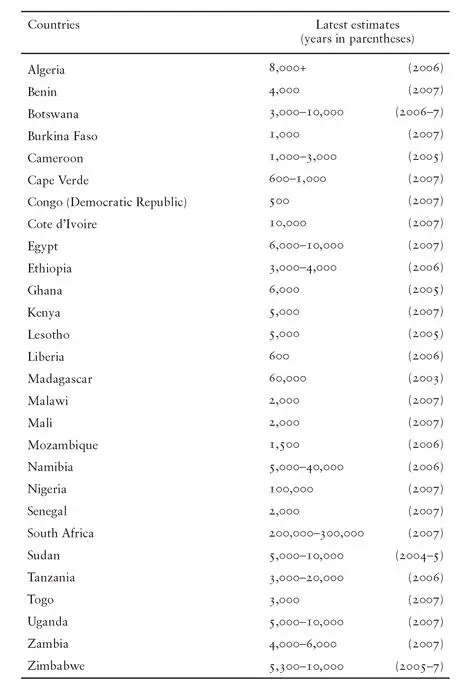

Table 5. Number of Chinese in selected African countries, 2003-7.

The contrasting approach of China and Western nations towards Africa, and developing countries in general, has led to a discussion amongst Africans about a distinctive Chinese model of development, characterized by large-scale, state-led investments in infrastructure and support services, and aid which is less tied to the donor’s economic interests and less overwhelmingly focused on the extraction of minerals as in the case of the West. [1076] [1076] Sautman and Yan, ‘Honour and Shame?’, p. 58.

China ’s phenomenal growth, together with the huge reduction in poverty there, has also provoked enormous interest in what lessons it might offer for other developing nations. [1077] [1077] Kaplinsky, ‘Winners and Losers’, pp. 12–13; Marks, introduction in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa , pp. 6–7.

An important characteristic of the Chinese model has been the idea of strong government and the eschewing of the notion of democracy, an approach which has an obvious appeal amongst the more authoritarian African governments. In the light of the country’s economic success, the Chinese approach to governance seems destined to enjoy a much wider influence and resonance in the developing world. The Chinese academic Zhang Wei-Wei has argued that the Chinese model combines a number of features. In contrast to the Washington Consensus, it rejects shock therapy and the big bang in favour of a process of gradual reform based on working through existing institutions. It is predicated upon a strong developmental state capable of steering and leading the process of reform. It involves a process of selective learning, or cultural borrowing: China has drawn on foreign ideas, including the neo-liberal American model, as well as many that have been home-grown. Finally, it embraces sequencing and priorities, as evidenced, for example, by a commitment to economic reforms first and political ones later, or the priority given to reforms in the coastal provinces before those in the inland provinces. [1078] [1078] Zhang Wei-Wei, ‘The Allure of the Chinese Model’, International Herald Tribune , 1 November 2006.

There has been considerable debate, in this context, about a Chinese model, sometimes described as the Beijing Consensus. There are certainly fundamental differences between the Chinese approach and the Washington Consensus, with the Chinese model both markedly less ideological and also distinctively pragmatic in the manner of the Asian tigers.

It is still far too early to make any considered judgement about the likely long-term merits and demerits of China ’s relationship with Africa. [1079] [1079] For an interesting discussion of China ’s involvement in Africa in a broader historical context, see Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, ‘East Mountain Tiger, West Mountain Tiger: China, the West, and “Colonialism” in Africa ’, Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies , 3 (2006).

The experience has been brief and the literature remains thin. The most obvious danger for Africa lies in the fundamental inequality that exists at the heart of their relationship: China’s economy is far bigger and more advanced, the nearest economic challenger, South Africa, being diminutive in comparison, while the population of Africa as a whole is less than that of China’s. The economic disparity between Africa and China, furthermore, seems likely to grow apace. Whatever the differences in approach between the Western powers and China, it seems likely that many of the problems in the relationship between the West and Africa, emanating from the fundamental structural inequality between them, seem likely to be reproduced in some degree in China ’s relationship with Africa. [1080] [1080] Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, ‘Friends and Interests: China ’s Distinctive Links with Africa ’, African Studies Review , 50:3 (December 2007), p. 78.

The danger facing African countries is that they get locked into being mere suppliers of primary commodities, unable for a variety of reasons — including unfavourable terms of trade and Chinese competition, together with domestic corruption and a lack of strategic will — to move beyond this and broaden their economic development through industrialization.

Читать дальше