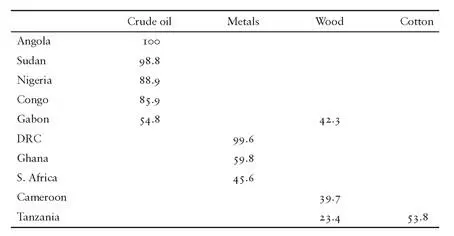

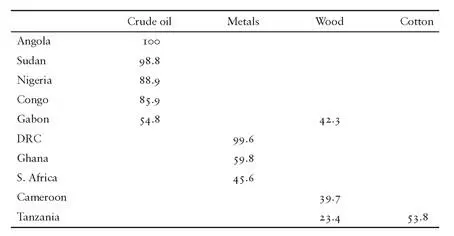

Table 3. China’s percentage share of certain commodities exported by African states.

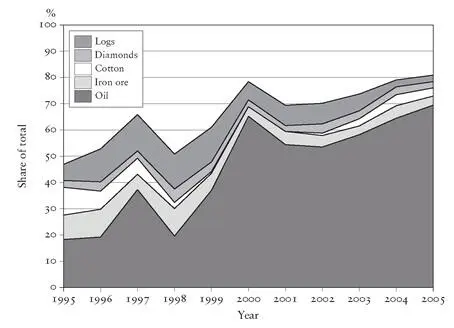

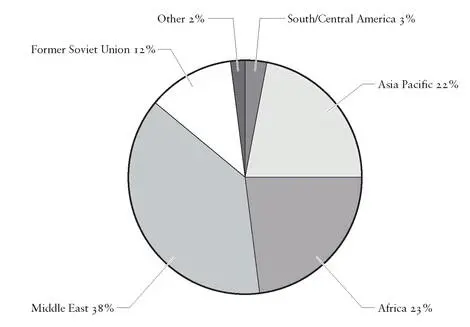

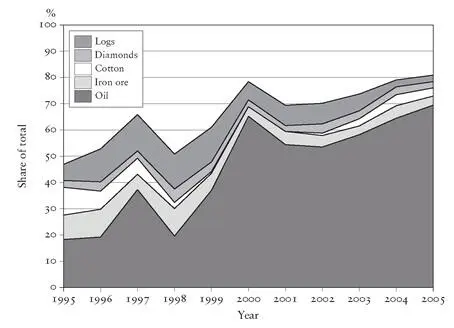

Figure 34. Composition of Chinese imports from sub-Saharan Africa.

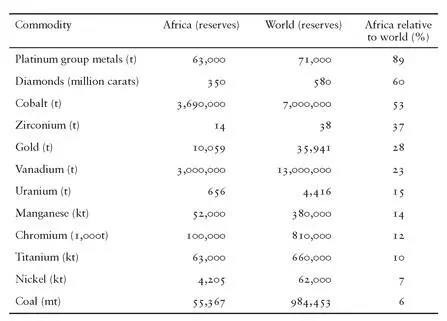

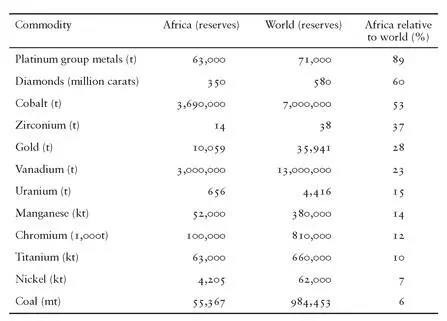

Table 4. Africa’s mineral reserves versus world reserves.

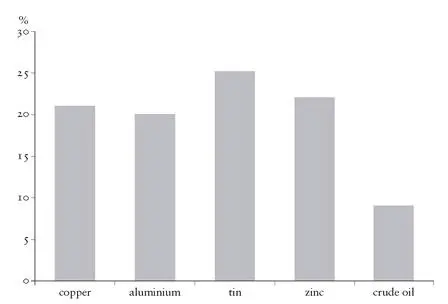

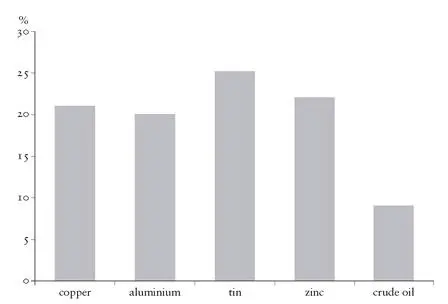

Figure 35. Chinese share of global consumption of commodities in 2006.

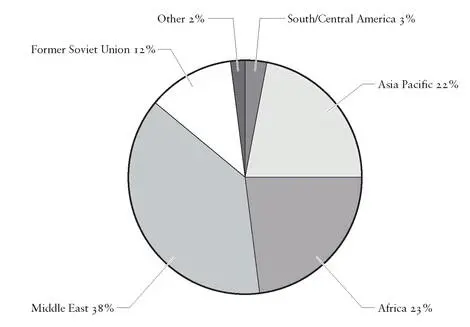

Figure 36. Where does China get its oil from?

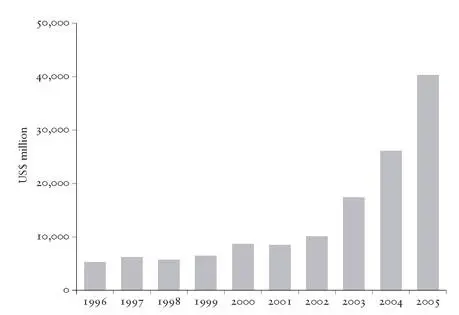

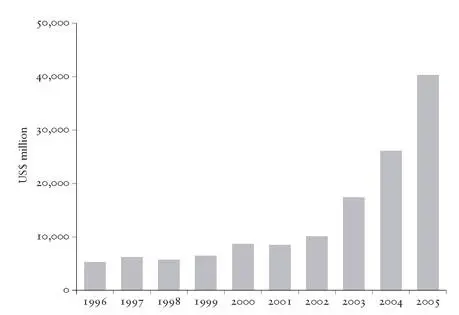

Figure 37. Rapid growth of China’s trade with Africa.

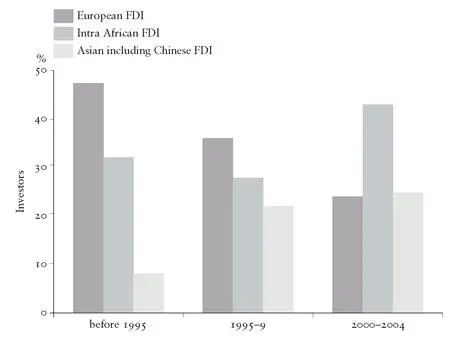

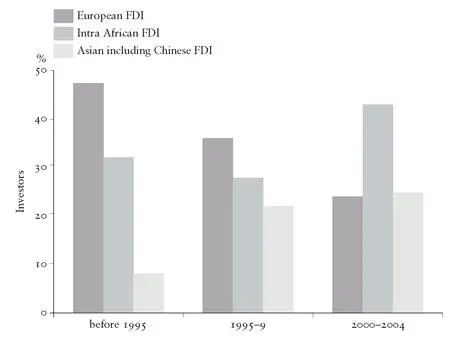

Figure 38. Foreign direct investors in sub-Saharan Africa.

Oil now accounts for over half of African exports to China, [1046] [1046] Daniel Large, ‘As the Beginning Ends: China ’s Return to Africa ’, in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa , p. 158.

with Angola having replaced Saudi Arabia as the country’s largest single oil provider, supplying 15 per cent of all its oil imports. [1047] [1047] Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, ‘Honour and Shame? China ’s Africa Ties in Comparative Context’, in Leni Wild and David Mepham, eds, The New Sinosphere (London: Institute for Public Policy Research, 2006), p. 54; Chris Alden, China in Africa (London: Zed Books, 2007), p. 67.

China has oil interests in Algeria, Angola, Chad, Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Congo and Nigeria, including substantial exploration rights, notably in Angola, Sudan and Nigeria. Sudan exports half of its oil to China, representing 5 per cent of the latter’s total oil needs. [1048] [1048] Ndubisi Obiorah, ‘Who’s Afraid of China in Africa? Towards an African Civil Society Perspective on China-Africa Relations’, in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa , pp. 47- 8.

Already over 31 per cent of all China’s oil imports come from Africa and that is set to rise with the purchase of significant stakes in Nigeria’s delta region. [1049] [1049] Alden, China in Africa , p. 12.

Over the past decade, China’s imports in all the major primary commodity categories, except ores and metals, grew much more rapidly from Africa than from the rest of the world. Africa now accounts for a massive 20 per cent of China’s total timber imports. [1050] [1050] John Rocha, ‘A New Frontier in the Exploitation of Africa’s Natural Resources: The Emergence of China’, in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa , p. 22.

China has overtaken the UK to become Africa’s third most important trading partner after the United States and France, though Africa still accounts for only 3 per cent of total Chinese trade. [1051] [1051] Leni Wild and David Mepham, introduction in Wild and Mepham, The New Sinosphere , p. 2.

While the value of US-Africa trade in 2006 was $71.1 billion, China-Africa trade is rapidly closing the gap at $50.5 billion. [1052] [1052] Alden, China in Africa , p. 104.

With 80 °China-financed projects, valued at around $1.25 billion in 2005 — before the 2006 conference — Chinese investment in Africa still accounts for only around 1 per cent of total foreign investments in Africa, but future projections suggest that China will very soon become one of the three top investors in the continent after France and the UK. [1053] [1053] Sautman and Yan, ‘Honour and Shame?’, p. 58.

It seems only a matter of time before China becomes Africa’s largest trading partner and its biggest source of foreign investment, probably by a wide margin, though India may one day emerge as a serious competitor.

The evidence of the growing Chinese presence in Africa is everywhere: Chinese stallholders in Zambia, Chinese lumberjacks in the Central African Republic, Chinese tourists in Zimbabwe, Chinese newspapers in South Africa, Chinese geologists in Sudan, Chinese channels on African satellite television. [1054] [1054] John Blessing Karumbidza, ‘Win-Win Economic Co-operation: Can China Save Zimbabwe’s Economy?’, in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa , p. 89.

There are estimated to be over 900 large- and medium-sized Chinese companies now operating in Africa, [1055] [1055] Alden, China in Africa , pp. 14, 39–40; Kitissou, Africa in China’s Global Strategy , p. 171.

together with a vast number of small-scale entrepreneurs, especially in the retail trade. Chinese shops, in particular, have proliferated with great speed, at times causing considerable alarm in the local African population: in Oshikango, Namibia, for example, the first shop was opened in 1999, by 2004 there were twenty-two shops, and by 2006 no less than seventy-five. In the Senegalese capital Dakar an entire city boulevard, a stretch of about a kilometre, is lined with Chinese shops selling imported women’s shoes, consumer durables such as glassware, and electronic goods at rock-bottom prices. [1056] [1056] Alden, China in Africa , p. 49; ‘A Troubled Frontier: Chinese Migrants in Senegal ’, South China Morning Post , 17 January 2008.

The rapidly growing number of direct flights between China and Africa are packed with Chinese businessmen, experts and construction workers; in contrast, there are few direct flights between Africa and the US, and the passengers are primarily aid workers with a smattering of tourists and businesspeople. [1057] [1057] Howard W. French, ‘Chinese See a Continent Rich with Possibilities’, International Herald Tribune , 15 June 2007.

The Chinese population in Africa has increased rapidly. It is estimated that it numbered 137,000 in 2001 but by 2007 had grown to over 400,000, compared with around 100,000 Western expatriates, and even this could be a serious underestimate. [1058] [1058] Sautman and Yan, ‘Honour and Shame?’, p. 59.

A more generous estimate, based on Table 5, suggests a Chinese population of over 500,000, but this is excluding Angola, where the figure is estimated at 40,000, and various other countries as well. [1059] [1059] Alden, China in Africa , pp. 52-3.

The present wave of Chinese migration is very different from earlier phases in the late nineteenth century and in the 1950s and 1960s. Apart from being on a much greater scale, the migrants now originate from all over China, rather than mainly from the south and east, and comprise a multitude of backgrounds, with many seemingly intent on permanent residence; the process, furthermore, is receiving the active encouragement of the Chinese government. [1060] [1060] Ibid., pp. 52-3, 55, 84-5.

The burgeoning Chinese population is matched by a growing number of prosperous middle-class Chinese tourists. Tourism accounts for a substantial part of foreign exchange receipts in some African countries like Kenya and the Gambia, and it is anticipated that there will be 100 million Chinese tourists annually visiting Africa in the near future. [1061] [1061] Abah Ofon, ‘South-South Co-operation: Can Africa Thrive with Chinese Investment? ’, in Wild and Mepham, The New Sinosphere , p. 27.

An ambitious tourism complex, for example, on Lumley Beach in Freetown, Sierra Leone — not one of the countries where Chinese influence is most pronounced — is in the pipeline, with an artist’s impression in the Ministry of Tourism showing pagoda-style apartments and Chinese tourists strolling around a central fountain. [1062] [1062] Lindsey Hilsum, ‘ China, Africa and the G8 — or Why Bob Geldof Needs to Wake Up’, in Wild and Mepham, The New Sinosphere , pp. 6–7.

A further significant illustration of the expanding Chinese presence in Africa is the growing contingent of Chinese troops involved in UN peacekeeping operations. In April 2002 there were only 11 °Chinese personnel worldwide but by April 2006 this had grown to 1,271 (with China rising from 46th to 14th in the international country ranking): revealingly, around 80 per cent of these troops are in Africa, placing it well above countries such as the UK, US, France and Germany. [1063] [1063] Mark Curtis and Claire Hickson, ‘Arming and Alarming? Arms Exports, Peace and Security’, in Wild and Mepham, The New Sinosphere , p. 41.

In total, over 3,00 °Chinese peace-keeping troops have participated in seven UN missions in Africa. [1064] [1064] Alden, China in Africa , p. 26.

Читать дальше