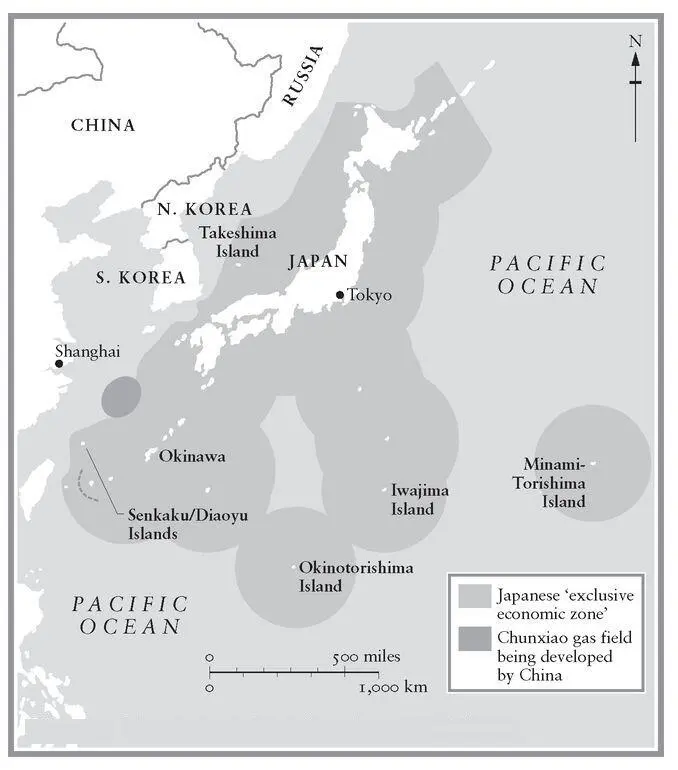

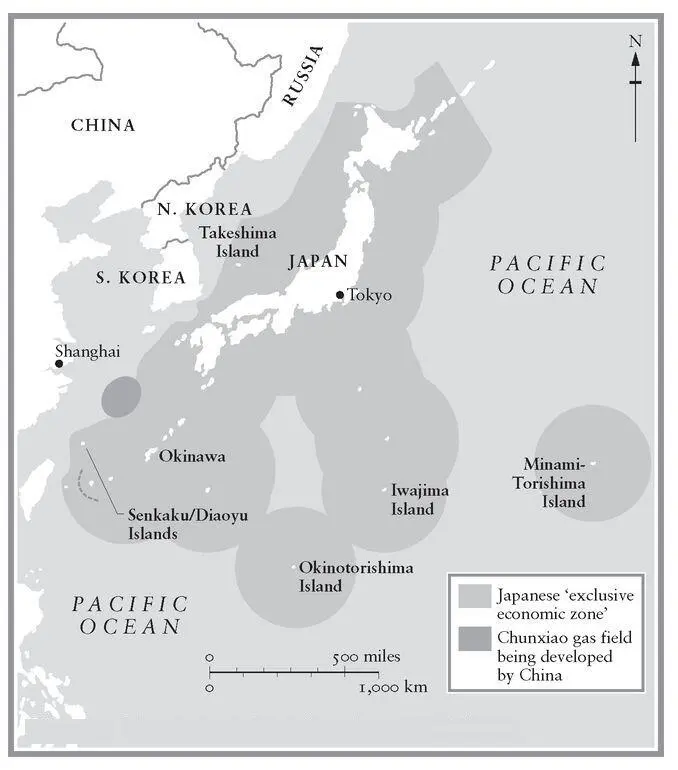

Map 12. The Disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands

So how is the relationship between China and Japan likely to evolve? There are several possible scenarios. [1023] [1023] For a different and optimistic view of their future relationship, based on demographic trends, see Howard W. French, ‘For Old Rivals, a Chance at a Grand New Bargain’, International Herald Tribune , 9 February 2007.

Hitherto, Japan has essentially regarded itself as different, and apart, from the region. As we have seen, that has been the case ever since the Meiji Restoration, with Japan looking up to the West and down on Asia. The fact that this mindset has been a fundamental characteristic of Japan ever since 1868 makes the task of changing it even more difficult and daunting. [1024] [1024] Martin Jacques, ‘Where is Japan?’, seminar paper presented at the Faculty of Media and Communications, Aichi University, 27 July 2005; Martin Jacques, ‘The Age of America or the Rise of the East: The Story of the 21st Century’, Aichi University Journal of International Affairs , 127 (March 2006), pp. 7–8.

Since its defeat in the Second World War, Japan’s detachment from Asia has been reinforced by its military dependence on the United States, with the American defence guarantee obliging Japan to look east across the Pacific Ocean rather than west to its own continent, thereby encouraging it to think of itself as an Asia- Pacific rather than East Asian power. This is illustrated by the fact that in 2007 it concluded a security pact — its only other being with the United States — with Australia, the US’s closest ally in the Asia-Pacific region. Though both unstated and denied, the obvious target of the agreement is China. [1025] [1025] ‘We’re Just Good Friends, Honest’, The Economist , 17 March 2007, p. 73.

Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the terms of its security and defence arrangement with the United States have been significantly strengthened over the last decade. [1026] [1026] Drifte, Japan’s Security Relations with China since 1989 , pp. 88–99; Thomas J. Christensen, ‘China, the US- Japan Alliance, and the Security Dilemma in East Asia’, in Brown et al., The Rise of China , pp. 148-9.

The most likely scenario is that Japan continues along this same path. For the Japanese it has the great advantage of enabling them to carry on with the status quo and postponing the day when they are required to engage in a fundamental rethink — by far the biggest since 1868 — of their relationship with China in particular and East Asia in general. In China ’s eyes, however, the US-Japan alliance is only the second worst solution, the worst — such are China ’s fears of Japanese history — being a Japan that increasingly aspires to become a military force in its own right. [1027] [1027] Christensen, ‘ China, the US — Japan Alliance, and the Security Dilemma in East Asia ’, p. 138.

The latter process is also under way, but it is taking place slowly and within the context of Japan ’s alliance with the United States, rather than separately from it. In the long run, however, dependence on the United States may be unsustainable. The growing economic, political and military strength of China could at some point oblige the Japanese to rethink their attitude towards China in a more positive way, while the United States may also be persuaded at some stage that its relationship with China is rather more important than that with Japan and that its alliance with Japan should effectively be downgraded, shelved or abandoned. But any such outcome, should it ever happen, still lies far in the future. [1028] [1028] Drifte, Japan ’s Security Relations with China since 1989 , pp. 180-82.

The one scenario that seems inconceivable is that Japan emerges as a stand-alone superpower to rival China: it is simply too small, too particularistic, too isolated and too weakly endowed with natural resources to be able to achieve this. [1029] [1029] Ross, ‘The Geography of Peace in East Asia ’, pp. 176-8.

The elephant in the room or, more precisely the region, is the United States. The latter is not even vaguely part of East Asia, being situated thousands of miles to its east, but with its military alliance with Japan, its military bases in South Korea and its long-term support for Taiwan, not to mention the Korean and Vietnamese wars, it has been the dominant power in the region ever since it replaced Europe in the 1950s. That state of affairs, however, has begun to change with remarkable speed. A combination of 9/11 and the new turn in Chinese foreign policy in East Asia, together with China’s emergence as the fulcrum of the regional economy — one of those accidental juxtapositions of history — has transformed Chinese influence in the region, while that of the United States, hugely preoccupied with the Middle East to the virtual exclusion of all else, it would seem, declined sharply during the Bush presidency. [1030] [1030] Interview with Shi Yinhong, Beijing, 19 May 2006; Strait Times , 6 February 2006; Jane Perlez, ‘As US Influence Wanes, a New Asian Community’, International Herald Tribune , 4 November 2004.

Given that the period involved has been less than a decade, the shift in the balance of power in the region has been dramatic. In a few short years, every single country has been obliged to rethink its attitude towards China and in every case — excepting Japan and Taiwan (though, since the election of Ma Ying-jeou as president, perhaps even there too) — has moved appreciably closer to it, including Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand and South Korea, all of which have formal bilateral alliances with the United States. [1031] [1031] Shambaugh, ‘ China Engages Asia’, p. 93; Kang, ‘Getting Asia Wrong’, pp. 58, 79, 81-2.

China ’s star in the region is patently on the rise and that of the United States on the wane. [1032] [1032] It is quite likely that the US will, over time, reduce its land-based military presence in the region; Pollack, ‘The Transformation of the Asian Security Order’, pp. 338-9, 343.

It would be wrong to assume that the future will be a simple extrapolation of these recent trends. The precipitous, for example, certainly cannot be excluded, especially in light of the open-ended nature of Sino-Taiwanese relations. Less apocalyptically, the process of change witnessed over the last decade could slow down, or alternatively perhaps accelerate. The United States could try to restrain the momentum and direction of that change by engaging in a more imaginative and proactive strategy towards East Asia under Obama. More speculatively, if relations between China and the US in East Asia should seriously worsen at some point in the future, the United States might seek to contain China. [1033] [1033] Kang, ‘Getting Asia Wrong’, p. 65.

If this should happen, then it would inevitably have serious ramifications for their global relationship. [1034] [1034] Zhang and Tang, ‘ China ’s Regional Strategy’, pp. 56-7.

But nor can the possibility be excluded that the US will in time become reconciled to its declining influence in East Asia. Should that be the case, there is little evidence so far to suggest that the region will become more unstable as a consequence: on the contrary, during the period that has coincided with China’s rise, East Asia has been, at least hitherto, strikingly conflict-free. Given that East Asia was characterized by long-term historical stability during the tributary period as a result of China ’s overwhelming power, this should not necessarily be regarded as surprising. [1035] [1035] Kang, ‘Getting Asia Wrong’, pp. 65-7, 79, 82-3.

Читать дальше