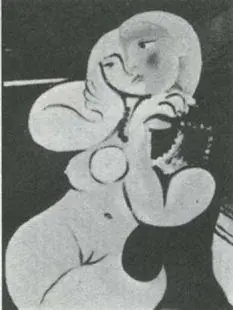

88 Picasso. The Mirror. 1932

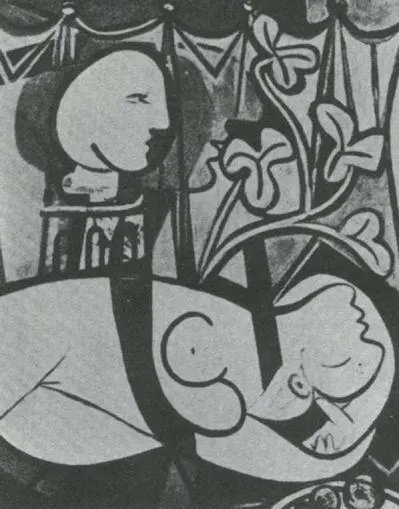

89 Picasso. Woman in a Red Armchair. 1932

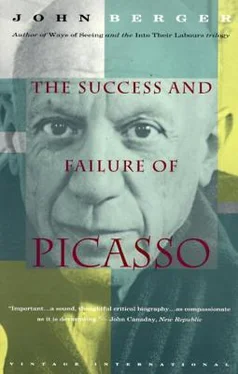

Today, among the five hundred or more of his own past paintings which Picasso owns, over fifty are of Marie-Thérèse. No other person dominates his collection a quarter as much. When he paints her, her subject is always able to withstand the pressure of his way of painting. This is because he is single-minded about her, and can see her as the most direct manifestation of his own feelings. He paints her like a Venus, but a Venus such as nobody else has ever painted.

What makes these paintings different is the degree of their direct sexuality. They refer without any ambiguity at all to the experience of making love to this woman. They describe sensations and, above all, the sensation of sexual comfort. Even when she is dressed or with her daughter (the daughter of Marie-Thérèse and Picasso was born in 1935) she is seen in the same way: soft as a cloud, easy, full of precise pleasures, and inexhaustible because alive and sentient. In literature the thrall which a particular woman’s body can have over a man has been described often. But words are abstract and can hide as much as they state. A visual image can reveal far more naturally the sweet mechanism of sex. One need only think of a drawing of a breast and then compare it to all the stray associations of the word, to see how this is so. At its most fundamental there aren’t any words for sex — only noises: yet there are shapes.

The old masters recognized this advantage of the visual. Most paintings have a far greater sexual content than is generally admitted. But when the subjects have been undisguisedly sexual, they have always in the past been placed in a social or moral perspective. All the great nudes imply a way of living. They are invitations to a particular philosophic view. They are comments on marriage, having mistresses, luxury, the golden age, or the joys of seduction. This is as true of a Giorgione as of a Renoir. The women lie there like conditional promises. The subjective experience of sex — the experience of the fulfilling of the promise — is ignored. (And ignored most pointedly of all in ‘pornographic’ pictures illustrating the sexual act.)

It is understandable that this should have been so in the past. There were stricter religious and social taboos. There was greater economic dependence of women and therefore a greater emphasis on the conventions of chastity and modesty. There was an established public role of art. A painting was painted for somebody else, so that ‘autobiographical’ painting was very rare; the subjective experience of sex can only be expressed autobiographically. There were also stylistic limitations.

The painter’s right to displace the parts — the right which Cubism won — is essential for creating a visual image that can correspond to sexual experience. Whatever the initial stimuli of appearances, sex itself defies them. It is both brighter and heavier than appearances, and finally it abandons both scale and identity.

These Picassos are, in a sense, nearer to drawings on lavatory walls than to the great nudes of the past. (Again, I am aware of giving arguments to the philistines, but I can scarcely believe that it matters any more — and philistinism anyway can never be argued with.) They are nearer to graffiti because they are so single-mindedly about making love. But they differ most profoundly from most graffiti in that they are tender instead of aggressive. The crudity of the average wall-drawing is not simply the result of a lack of skill. Such drawings are nearly always a protest against deprivation: an expression of frustration. And within this frustration there is both desire and resentment. Thus the crudeness of the drawings is also a way of insulting the sex that has been denied. The Picassos, by contrast, praise the sex they have enjoyed. Here for everybody to recognize are William Blake’s ‘lineaments of satisfied desire’.

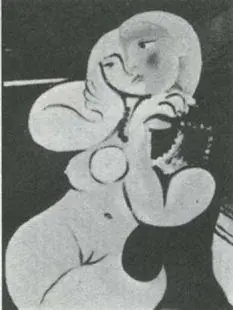

90 Picasso. Nude. 1933

It is no longer possible to say whether these ‘lineaments’ are an expression of Picasso’s pleasure in the woman’s body, or a description of her pleasure. The paintings, because they describe sensation, are highly subjective, but part of the very force of sex lies in the fact that its subjectivity is mutual. In these paintings Picasso is no more just himself: he is the two of them, and their shared subjectivity includes in some part or another the experience of all lovers.

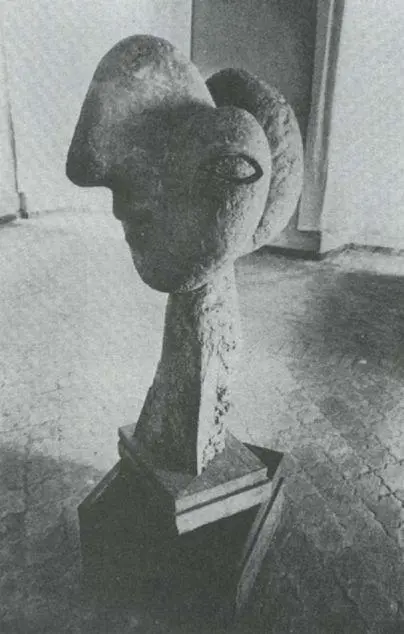

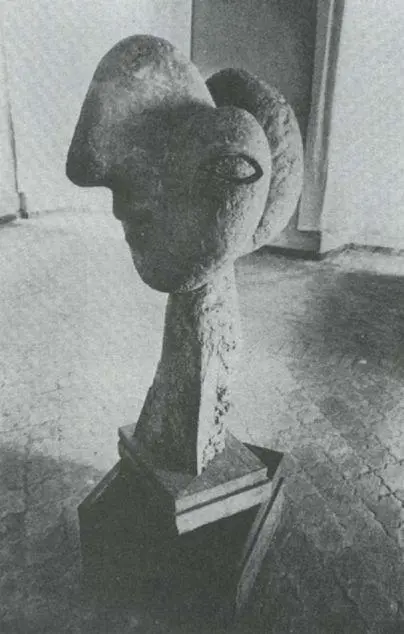

In a sculpture of the same period this shared subjectivity becomes the underlying theme of the work.

91 Picasso. Head of Woman (bronze). 1931-2

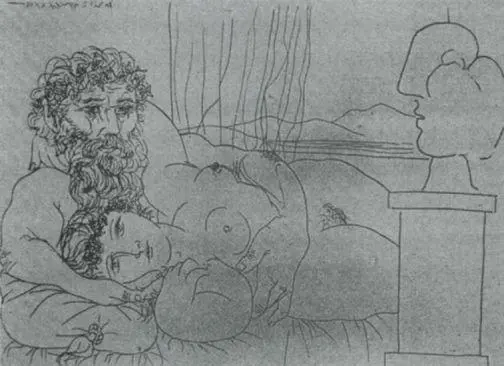

Picasso made several variations of this head and it is the same head which appears in his etchings of the artist in his studio. It is identified with Marie-Thérèse, but is by no means a portrait. In the etchings it stands there in the studio like a silent oracle, looking at the sculptor and his model who are lovers.

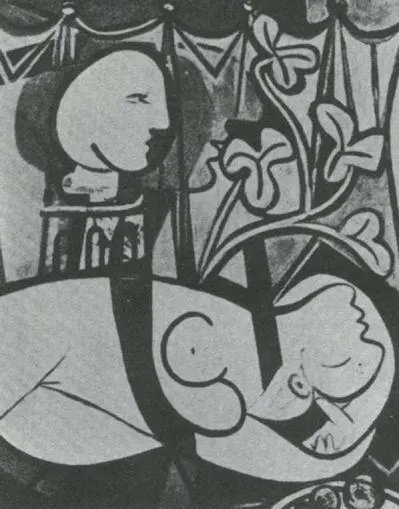

92 Picasso. Sculptor and Model Resting. 1933

Its secret is a metaphor. It represents a face. Yet this face is reduced to two features: the nose, rounded and powerful, which thrusts forward and is simultaneously heavy and buoyant; and below it, the mouth, soft, open, and very deeply modelled. In terms of the density of their implied substance, the nose is like wood and the mouth like earth. These two features emerge from three rounded forms which have been formalized from the cheeks and the bun of hair at the back of the head. The scale of the work is what first offers a clue to the metaphor. It is very much larger than a head — one stands looking at it as at a figure, a torso. Then one sees. The nose and the mouth are metaphors for the male and female sexual organs; the rounded forms for buttocks and thighs. This face, or head, embodies the sexual experience of two lovers, its eyes engraved upon their legs. What image could better express the shared subjectivity which sex allows than the smile of such a face?

Picasso may have arrived at the metaphor unconsciously. But afterwards he deliberately played with the idea of transforming a head into sexually charged component parts. One can see the process at work in a sequence of drawings like this:

93 Picasso. Page of drawings. 1936

Perhaps the same reference also applies to some of the desperately bitter heads of the early forties. Like the Nude with a Musician (but less successfully) they too are paintings about a hateful impotence.

94 Picasso. Head of a Woman. 1943

It is as though — and here Picasso is like most of us — he can only fully see himself when he is reflected in a woman. And it is as though — and here he is rarer — it is almost only through the marvellous shared subjectivity of sex that he can allow himself to be known. The majority of his paintings are of women. There are surprisingly few men. A number of the women are portrayed as themselves. Others are idealizations. But most of them are composite creatures — themselves and he together. In a sense these paintings might be called self-portraits — not portraits of himself alone and untransformed, but self-portraits of the creature he and the woman became as they sensed one another. The relationship is always sexual but the preoccupations of the composite creature may not be. It is when this happens that the painting becomes absurd and destroys itself — as was the case with the Nude Dressing her Hair . Shared subjectivity can no longer exist except when the aim is sex. It becomes instead a form of megalomania.

Читать дальше