Now I have come.

Once more this limping life before me, no not this life, this death, this death without sense or piety, this death where greatness pitifully fails, this death which limps from pettiness to pettiness; little greeds heaped on top of the conquistador; little flunkeys heaped on top of the great savage; little souls shovelled on top of the three-souled Caribbean.

Later he recovers from his disappointment, and pledges himself to his people, since it is only by such identification that the magic can be wrought, the magic of a ‘fraternal earth’.

And here at the end of the small hours is my virile prayer

that I may hear neither laughter nor crying, my eyes

upon this city which I prophesy as beautiful.

Give me the sorcerer’s savage faith

give my hands the power to mould

give my soul the temper of the sword,

I will stand firm. Make of my head a prow

and of myself make neither a father,

nor a brother, nor a son,

but the father, but the brother, but the son,

nor make of me a husband, but the lover of this unique people.

I quote Césaire at such length because today it is hard for most Western European intellectuals to imagine the devotion which an artist may feel for his ‘unique people’. This devotion is the result of mutual dependence. The people need a spokesman — the fact that Césaire is a French Deputy is almost as important as his being a poet; the artist needs the clamour and hopes of those whom he represents.

For Picasso there has been no such ‘unique people’. He has exiled himself from Spain. He has seldom left France, and in France he has lived like an emperor in his own private court. Such facts would not necessarily count if he could still have identified himself in imagination with a ‘unique people’. But the unique people have been reduced to a unique person, who only half exists by virtue of his contrast with everybody else: the noble savage.

We must now return to the consequences of Picasso’s isolation as they have affected his art. He has not lacked appreciation. Nor has he lacked creativity. What he has lacked are subjects.

When it comes to it, there are very few subjects. Everybody repeats them. Venus and Cupid becomes the Virgin and Child, then a Mother and Child, but it’s always the same subject. To invent a new subject must be wonderful. Take Van Gogh. His potatoes — such an everyday thing. To have painted that — or his old boots! That was really something.

In this statement — it was part of a conversation with his old dealer Kahnweiler in 1955 — Picasso unwittingly reveals his difficulty. No other statement tells us so much about the fundamental problem of his art. Only in the crudest sense is a Venus and Cupid the same subject as a Virgin and Child. One might as well say that all landscapes from the early Italians to Monet are the same subject. The meaning of a Venus and Cupid, the significance of all that has been selected to be included in the picture, is totally different from that of a Virgin and Child, even when the latter is secular and has lost its religious conviction. The two subjects depend on an utterly different agreement being imagined between painter and spectator.

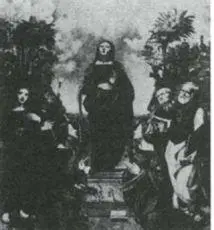

75 Piero di Cosimo. The Immaculate Conception

76 Piero di Cosimo. The Finding of Vulcan on Lemnos

Compare these two paintings by Piero di Cosimo (1462–1521?), and in particular the central figure. In so far as she is the same woman with the same face, one could say that she is the same subject — no matter whether real or imaginary. Yet to say this is to limit the whole concept of the subject to the relationship between the painter and the painted image. It ignores what the painter is trying to say, and it dismisses the effect of the painting. The subject, instead of bringing into being or affirming an agreement between the painter and the spectator, is now reduced to a mere description of what the painter’s hand is cataloguing. Such a view of what constitutes the subject of a work of art suggests a man so used to working alone that he has forgotten the possibility of agreement with anybody else. One is again reminded of the loneliness of a lunatic who, at the same time, is sane enough to know that it is useless to explain.

Certainly Van Gogh painted new subjects. But they were not ‘inventions’. They were what he naturally found as a result of his self-identification with others. All new subjects have been introduced into painting in the same way. Bellini’s nudes, Breughel’s villages, Hogarth’s prisons, Goya’s tortures, Géricault’s madhouse, Courbet’s labourers — all have been the result of the artist identifying himself with those who had previously been ignored or dismissed. One can even go so far as to say that, in the last analysis, all their subjects are given to artists. Very few, such as he has been able to accept, have been given to Picasso. And this is his complaint.

When Picasso has found his subjects, he has produced a number of masterpieces. When he has not, he has produced paintings which eventually will be seen to be absurd. They are already absurd, but nobody has had the courage to say so for fear of encouraging the philistines for whom all art, because it is not a flattering looking-glass, is absurd.

Let me give some examples of when he has failed to find (or be given) his proper subject.

77 Picasso. The Race. 1922

The Race was painted in Picasso’s so-called Classic period. (Many artists went ‘classic’ at this time as if to forget the barbarism of the eight million dead of the war.) It was also the time, as we have seen, when Picasso was ‘impersonating’ various styles. There is to some extent a consciously absurd element in this painting. Yet where is the absurdity? Surely it lies in the fact that two such monumental giantesses are running so wildly, with such abandon. If, with their massive, formalized, marmoreal limbs, they are to be credible at all, they must be statuesque. By making them run like hares Picasso disconcertingly destroys their very raison d’étre. The same thing happens stylistically: the figures are drawn with a kind of ponderous simplified logic of classical light-and-shade; yet the perspective which makes the nearest hand smallest and the farthest hand largest upturns that same logic and makes it absurd. There is also a similar reversal in emotional terms. Such figures are a caricature of all that is imperturbable, calm and timeless. Then suddenly they are set fleeing with an urgency that amounts to panic.

Perhaps this was precisely Picasso’s intention, but I doubt it. He was impersonating; he was also interested in the Surrealists and their cult of the irrational; he probably wanted to make a picture that looked odd and was disturbing. But what he has achieved is a painting that cancels itself. It is true that at first it communicates a kind of shockbut this shock, by its very nature, precludes its communicating anything else. It is like seeing a candle blow itself out.

Читать дальше