Because we know how directly and unintellectually Picasso works, it seems very unlikely that this was his real aim. And it seems far more likely that, having these monumental giantesses in his head (he had been painting them for two years), he tried to say something with them which they weren’t capable of ‘containing’. And thus his purpose or the compulsion of his feelings destroyed his subject because it was the wrong one.

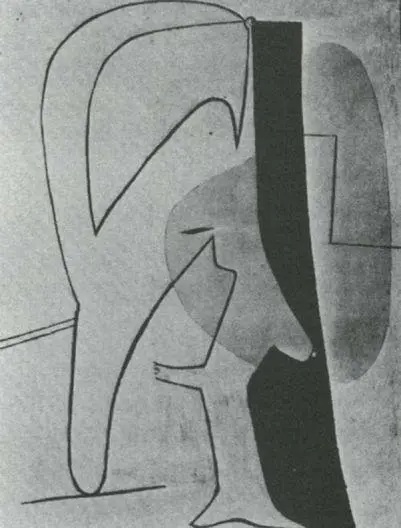

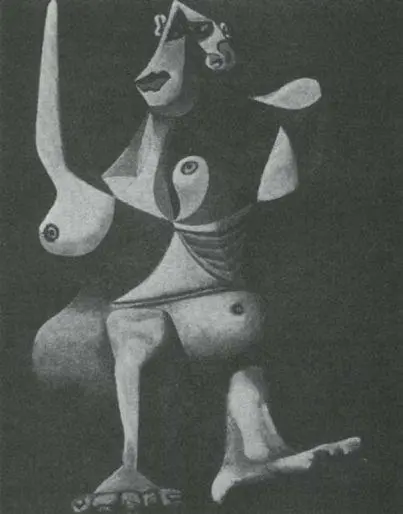

In the 1927 Figure , it seems that the subject (a nude woman) has been so destroyed that it is no longer identifiable. Yet if one goes on looking, one finds the clues — the tiny pin-head at the top, the arm going up to it, the breast and nipple displaced towards the bottom right, the mouth of the vagina, like a cut, almost in the centre of the picture. Although superficially the picture may look like a Cubist collage, there is no interest here in structure or the dimensions of time and space; it is obsessionally, impatiently sexual. But its sexuality is without a subject. It is as though this picture were crying out for a Leda and the Swan, or a Nymph and Shepherd, or a Venus, to be given a form. But there is nobody to call that form into being, nobody to name it and separate it from Picasso by believing in it. What Picasso is expressing here becomes absurd because there is nothing to resist him: neither the subject, nor his awareness of reality as understood by others. Without such resistance the whole of Shakespeare’s Lear would be no more than a death-rattle.

78 Picasso. Figure. 1927

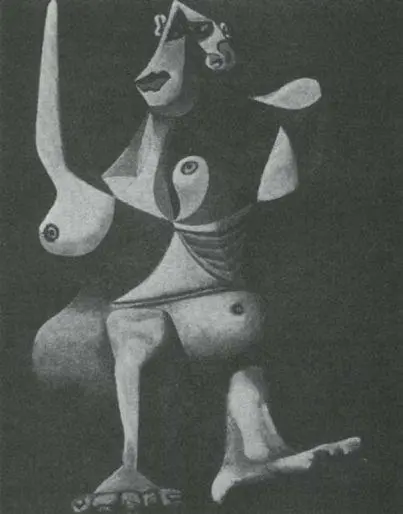

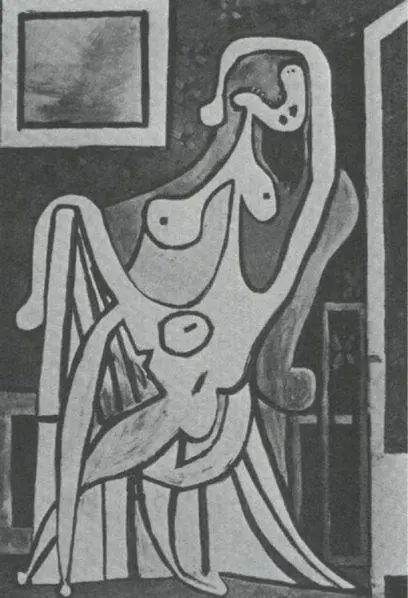

The Woman in an Arm-chair is less distorted. Nobody can fail to see that this represents a woman. People may pretend to themselves that they can’t disentangle the figure, because it constitutes such a violent attack on their sense of propriety; but recognizing the attack, they also recognize the figure. Nevertheless, the painting is as absurd as the last one, and the subject has again been destroyed — although in a different way. The motive of the painting is no longer straightforwardly sexual, but far more bitterly and desperately emotional. It is for this reason that the physical displacements of the body are far less extreme, but the overall effect more violent. There is no Venus behind this picture; rather one of the Seven Deadly Sins, feared, resented, and yet undismissible. It is absurd because, removed from the medieval context of Heaven and Hell, the violence of the emotion conveyed and yet not explained and not related to anything else, destroys our belief in the subject. It is perfectly possible to believe that Picasso felt like that, but we cannot share this feeling with him because it cannot be understood or evaluated on the evidence of what he shows us. We have no way of telling whether it is noble anger or petulance. All we can recognize is that he is disturbed. What disturbed him we do not know — because he has not been able to find the subject to contain his emotion.

79 Picasso. Woman in an Arm-chair. 1929

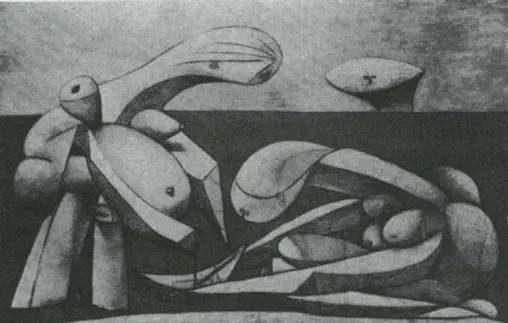

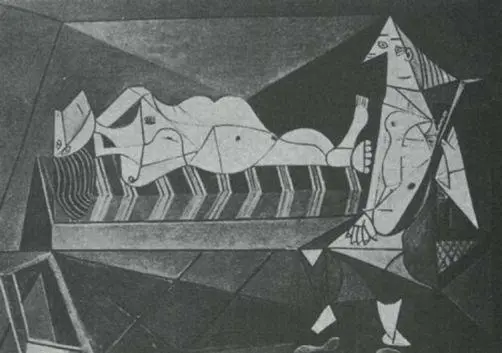

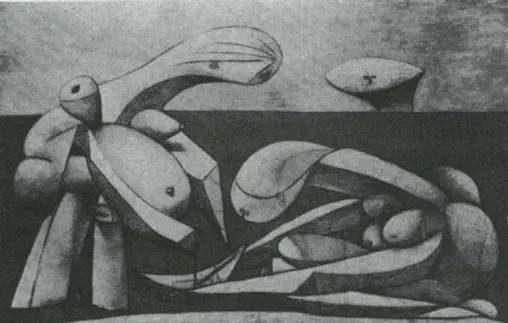

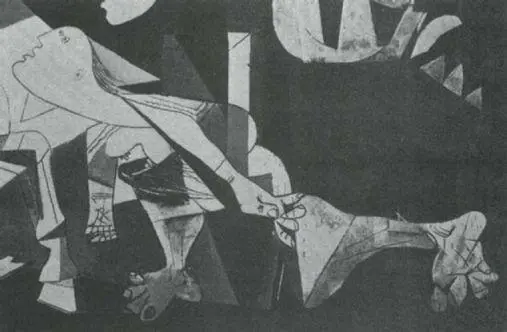

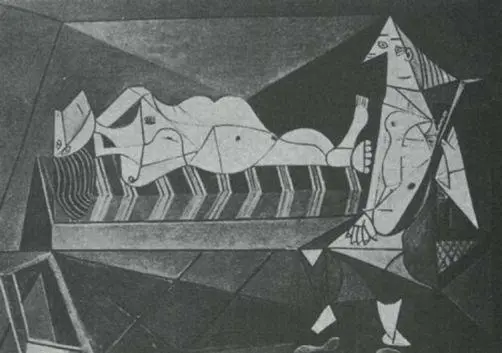

In Girls with a Toy Boat the problem is different. It isn’t now a question of Picasso being driven by a feeling or emotion which he cannot house in a subject; here he gives himself up to his own ingenuity, and the absurdity arises because he appears to ignore the emotive power of the forms with which he is playing. He is planning a new (and momentary) human anatomy, as schoolboys plan rockets or perpetual-motion machines. His method of drawing is very precise and three-dimensional, so that it would be quite easy to construct one of these figures out of wood or paper. This tangibility increases the absurdity. Such ‘real’ breasts, buttocks, and stomachs attached to such machines are bound to make us laugh in order to release the tension of the emotion provoked by the sexually charged parts and then belied by all the rest. A similar inconsistency is implied by the action. If they are children playing with a boat, why have they women’s bodies? If they are women, why the toy boat? It may seem naïve to ask such a logical question of a painting in which a head can peer over the horizon as though over the edge of a table. Of course Picasso was joking, trying to shock, playing at contradictions. But this was because he didn’t know what else to do. And the comparatively untransformed sexual parts, so inconsistent with the rest, are an indication of this indecision. Within three months of painting this picture, he was painting Guernica ; it is worth comparing these figures with one of the figures there.

80 Picasso. Girls with a Toy Boat. 1937

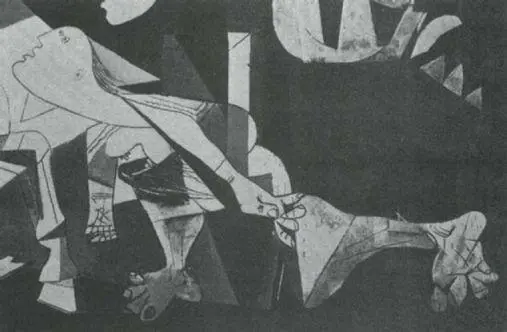

81 Picasso. Guernica (detail). 1937

Every part of the body of the woman in Guernica contributes to the same end; her hands, her trailing leg, her twisted buttocks, her sharp nipples, her craning head — all bear witness to what at this moment is her single ability: the ability to suffer pain. The contrast between the two paintings is extraordinary. Yet in many ways the figures are similar, and without the exercise of paintings like Girls with a Toy Boat Picasso would never have painted Guernica in the way he did. The difference is one of single-mindedness. Yet to be single-minded you have to know what you want. And for Picasso to know what he wants, he has first to find his subject.

82 Picasso. Nude Dressing her Hair. 1940

Picasso painted the 1940 nude immediately after the defeat of France, whilst the German troops were occupying Royan, on the Atlantic coast, where he had fled. It is an anguished painting, and if one knows of the circumstances in which it was painted, it becomes an understandable picture. But it remains absurd, even if horrifically absurd. To see why this is so, let us again make a comparison with a successful painting. Both pictures are the result of the same experience — the experience of defeat, occupation, and a terrible vision of evil, which was in no sense metaphysical, but there in the streets in its jackboots and with its swastika.

83 Picasso. Nude with a Musician. 1942

This second picture, painted two years later, is no more explicit about the general experience from which it derives, but it is self-contained and consistent. The experience has found a subject. The subject, baldly described in words, may seem unremarkable: a woman on a bed and another woman sitting on a chair, holding a mandolin which she is not playing. Yet in the relationship between these two women and the furniture and the room that closes in around them, without a window or a door, there is all the claustrophobia of the curfew and a city without freedom. It is like making love in a cell where there is never any daylight. It is as though the sex of the woman on the bed and the music of the mandolin had been deprived of all their resonance, because such resonance requires a minimum freedom within which to vibrate. The real subject is not simply the two women, but the state of being confined in this room. In Picasso’s mind, as he painted it, there must have been an image of such a room, an image of curfew, to which he could refer and through which he could express his emotion.

Читать дальше