The Nude Dressing her Hair squats in an even more celllike room. But because there is no consistency between the parts (just as was the case with the Toy Boat ) we are unable to accept the scene as a self-contained whole. None of the parts refers to each other: instead, each, separately, refers to us, and we then refer it back to Picasso. A normal mouth forms part of a slashed, displaced face. The underneath of a foot, seen as by a chiropodist, joins on to a butcher’s bone which ends in a stone stomach. It is true that the figure as a whole does pose one question: Is this a woman or a trussed fowl? And from that question we can deduce bestial indignities. But the question remains, as it were, rhetorical. We do not believe in the woman being a trussed fowl, we believe only in Picasso wanting to make her look like that. In the end we are left face to face with what seems to be Picasso’s wilfulness. And it seems thus because he has not been able to express himself, because he has not been able to include his emotion in his subject but only impose his emotion upon it.

Some may see the difference between these two paintings as principally one of style. In the Nude with a Musician there is stylistic consistency. The way an eye is rendered is compatible with the way a hand, a foot, or hair is rendered. All are equidistant from (photographic) appearances. In the other painting there is deliberate stylistic inconsistency. Yet the true difference is more profound than this. We can imaginatively enter the first picture and as we proceed, moving from one part to another, we gather emotion. In front of the Nude Dressing her Hair , we never get beyond the violence that each part does to the next. No emotion develops because it is short-circuited by shock. And that is exactly what happened when Picasso was painting it; he short-circuited his own emotion, because he could find no circuit for it through a subject. A woman’s body by itself cannot be made to express all the horrors of fascism. But Picasso clung to this subject because, at that moment of fear and crisis, it was the only one of which he felt certain. It is the earliest subject in art, and modern Europe had failed to give him any other.

All that we have noticed about inconsistencies in the Nude Dressing her Hair applies equally to First Steps. Again this painting does no more than confront us with the evidence of Picasso’s apparent wilfulness. But this time with far less reason, for the emotional charge is much smaller. It is not now a cri de cœur which tragically fails to achieve art, but mannerism.

84 Picasso. First Steps. 1943

The experience is Picasso’s experience of his own way of painting. It is like an actor being fascinated by the sound of his own voice or the look of his own actions. Self-consciousness is necessary for all artists, but this is the vanity of self-consciousness. It is a form of narcissism: it is the beginning of Picasso impersonating himself. When we look at the Nude Dressing her Hair we are at least made to feel shock. Here we only become aware of the way in which the picture is painted — and this can be called clever or perverse according to taste.

It would be petty to draw attention to such a failure if it was incidental. What artist has not sometimes been vain or self-indulgent? But later, after 1945, a great deal of Picasso’s work became mannered. And at the root-cause of this mannerism there is still the same problem: the lack of subjects — so that the artist’s own art becomes his subject.

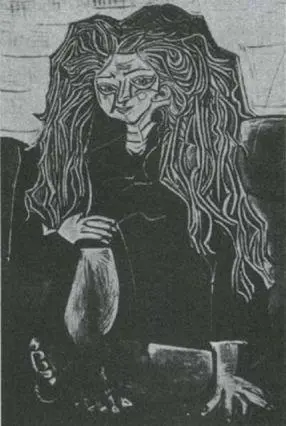

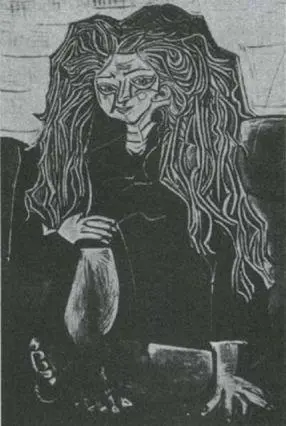

85 Picasso. Portrait of Mrs H. P. 1952

The Portrait of Mrs H. P. is a typical later example. The style is different, but not the degree of mannerism. So much is happening in terms of painting — the hair like a maelstrom, the legs and the hand painted fast and furiously, the face with its strange, abrupt hieroglyphs of expression — but what does it all add up to? What does it tell us about the sitter except that she has long hair? What is all the drama about? Unhappily, it is about being painted by Picasso. And that is the extremity of mannerism, the extremity of a genius who has nothing to which to apply himself.

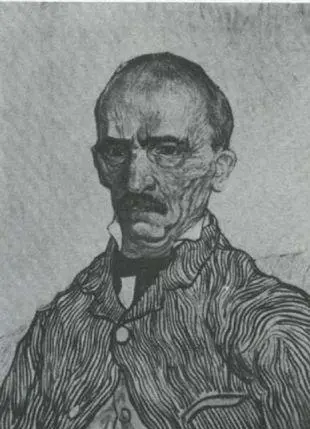

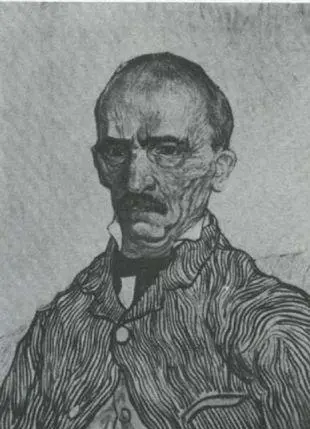

To show how much a dramatically painted portrait can say, let me quote, without comment, a portrait by Van Gogh.

86 Van Gogh. Portrait of the Chief Superintendent of the Asylum at Saint-Remy. 1889

On the evidence of seven paintings I have tried to show you how, from about 1920 onwards, Picasso has sometimes failed to find subjects with which to express himself, and how, when this happens, he virtually destroys the nominal subject he has taken, and so makes the whole painting absurd. There are other paintings in which this has happened. There are even more in which it has partially happened. There are also paintings in which he has found his subject.

It would be as stupid to deny the originality of Picasso’s failures as to pretend that this originality transforms them into masterpieces. Picasso is unique but, since he is a man and not a god, it is our responsibility to judge the value of this uniqueness.

It is not my intention to draw up a definitive list of Picasso’s failures as opposed to his masterpieces. What I hope I have shown is the relevance of asking a particular question about Picasso. The question, I believe, leads to a standard by which all his work can usefully be judged.

Apart from the Cubist years, nearly all Picasso’s most successful paintings belong to the period from 1931 to 1942 or 43. During this decade he at one moment — in 1935 — gave up painting altogether. It was a time of great inner stress. But it was also the period when he most successfully found his subjects. These subjects were related to two profound personal experiences: a passionate love affair, and the triumph of fascism first in Spain and then in Europe.

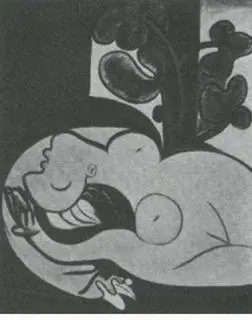

In the countless books about Picasso no secret is ever made of his many love affairs; indeed they have become part of the legend. Only one affair is passed over quickly — and that is the one to which I now refer. It is typical of the lack of realism which surrounds Picasso’s reputation that this should be the case. There is no need to pry into his private life — even though this is so often and tastelessly described by his friends; but one fact has to be noted, because it is so directly related to his art. On the evidence of his paintings, his sculpture, and hundreds of drawings in sketchbooks, the sexually most important affair of his life was with Marie-Thérèse Walter whom he first met in 1931. He has painted and drawn no other woman in the same way, and no other woman half as many times. It may be that she became a kind of symbol for him, and that in time the idea of her meant more to him than she herself. It may be that in the full sense of the word he was more devoted to other women. I do not know. But there is not the slightest doubt that for eight years he was haunted by her — if one can use a word normally applied to spirits to refer to somebody whose body was so alive for him.

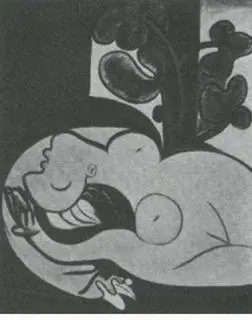

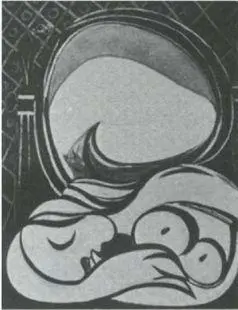

87 Picasso. Nude on a Black Couch. 1932

Читать дальше