Just as Picasso abstracts sex from society and returns it to nature, so here he abstracts pain and fear from history and returns them to a protesting nature. All the great prosecuting paintings of the past have appealed to a higher judge — either divine or human. Picasso appeals to nothing more elevated than our instinct for survival. Yet this appeal now confirms the most sophisticated assessment of the realities of the modern world, which the political leaders of both the East and the West have been obliged to accept.

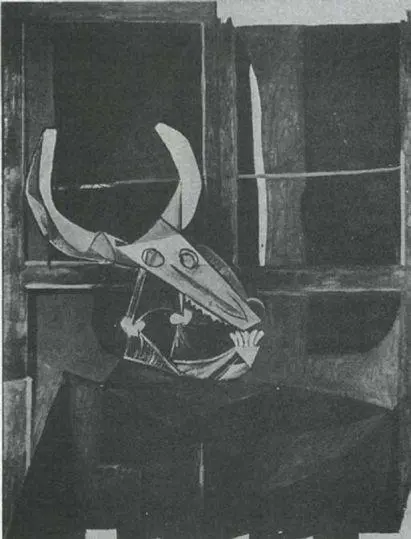

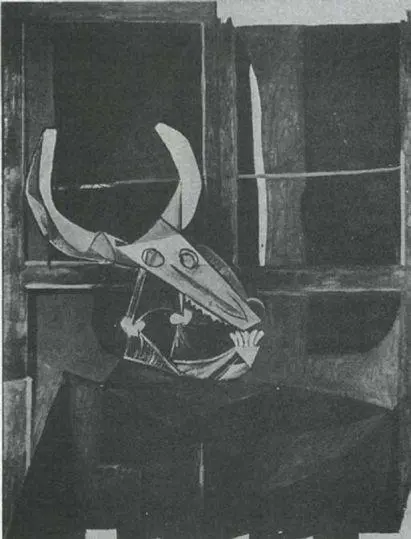

The successful pictures that Picasso painted after Guernica act at the same level of experience: a level of intense physical subjectivity. There are the still-lifes of animal skulls and heads which he painted during the first years of the German occupation. These are really further studies of the agonized horse’s head in Guernica . They are tragedies of the flesh. The difference is that everything now is still and silent.

100 Picasso. Still-life with Bull’s Skull. 1942

The major work after Guernica is the Nude with a Musician which we have already examined. But now we can see how it is related to the nudes of Marie-Thérèse. It is all that they are not. It is their lament. The body of the woman on the bed is the loss of all their pleasure. No traditional contrast between youth and age is half so pointed because there the differences are objective — the breasts shrink, the back bends; here the contrast is subjective too. Once more it is impossible to distinguish between the joy-lessness of her body and his joylessness in her. What they both experience now is deprivation. It is a painting about the physical sensation of absence. Whether the absence is of freedom, of food, of passion, of hope, or of the other person, is not important — and for Picasso it may again have had so many meanings that he himself could not have explained it further.

By 1943 the second and last great period of Picasso’s life as an artist had ended. During that period he had painted some bad pictures but he had also painted some great ones. After 1943 he produced nothing comparable. Why could he not go on as before? Picasso’s great paintings from 1931 to 1943 were all, including Guernica — and that is where so many critics have been misled — autobiographical. They were confessions of highly personal and very immediate experiences. They embody no social imagination in the usual modern sense of the word. The first paintings were about sexual pleasure; the tragic paintings of Guernica and the war were about pain and were the obverse of the erotic paintings. All of them were concerned with expressing sensations. All of them exploited the freedom to displace parts — the freedom won by Cubism — to achieve their aim.

To find these subjects Picasso scarcely had to leave his own body. It is through the experience of his own body that he painted erotic pictures, and it is through his own physical imagination, heightened by sexual experience, that he painted the war pictures. (It is interesting to note that in the latter almost all the figures are women.) The choice of his successful subjects was limited to what was happening to him at a very basic level. At that level — a level which no European painter had ever before investigated so deeply — the special significance or meaning of a subject is biologically rather than culturally assured. At that level — if we have the courage to admit it — we are all one.

To have continued painting like this would have meant continuing to live as intensely and eventfully as during the last decade. At the age of sixty-two this was probably impossible. But anyway it was not something which could be willed or chosen. The affair with Marie-Thérese was over, and, although other women took her place, the same passions were not involved. The Spanish War was ended and nothing again was likely to possess Picasso like the news of that civil war in his own country had done. The Nazis were being beaten at Stalingrad: in a year Paris was to be liberated. Partly because of his age, partly because of the course of world events, it was no longer possible for Picasso to feel that the initiatives remained with him. He saw and imagined the experiences of others as being more intense and more significant than his own. He had to discount his own body — and with it, its subjects.

There were also positive reasons why Picasso may have wanted at this time to begin a new phase of his working life. Having lived through the occupation and so experienced political events at first hand, as he had not done since his youth in Spain, he was genuinely moved by political emotions. Most of his friends were in the Resistance, and he himself, although he took no part, nevertheless became a figure-head of the movement. When at last Europe was liberated, he felt — like millions of others — that he must assist the birth of a new world. And in 1944 he joined the French Communist Party.

This was a moment of truth which it had taken him fifty years to arrive at. It was the moment when Picasso acted and chose so as to come to terms with both the reality around him and his own genius.

Ever since Picasso first arrived in Western Europe he had been critical of what he saw. Except for the Cubist years, when he was under the influence of others, his criticisms were expressed by his repeatedly shown preference for the primitive. Like Rousseau, he opposed nature to society. Such a ‘revolutionary’ attitude, valid a hundred and fifty years ago, is now outdated. Revolutionary philosophy today is materialist, and the only revolutionaries really feared by capitalism are marxists. And so, by joining the Communist Party, Picasso for the first time made his revolutionary feelings effective in terms of modern reality.

Picasso’s genius is of a type that requires inspiration from other people. He is a spokesman or seer for others. He is in no sense the solitary modern investigator, for he hasn’t sufficient faith in reason or progress in art. Denied such inspiration by the milieux in which he moved after 1914, he often failed to find subjects to contain his emotions. At the same time he was forced to search within himself for an equivalent inspiration. To some extent he found it by idealizing his alter ego as a ‘noble savage’. During the thirties and early forties this ambiguous contract within himself allowed him to create some highly original masterpieces: paintings in which, with all his skill and sophistication as an artist, he acts as a spokesman for his own instinctual experiences. But this could not continue indefinitely, for it was too inverted. He needed inspiration from those to whom he could belong, rather than from what, inevitably, belonged to him. He needed what Aimé Césaire calls his ‘unique people’. By joining the Communist Party this is what he hoped to find. If he found it, his genius would be released as never before.

Explaining his decision, he spoke as follows:

Have not the Communists been the bravest in France, in the Soviet Union, and in my own Spain? How could I have hesitated? The fear to commit myself? But on the contrary I have never felt freer, never felt more complete. And then I have been so impatient to find a country again: I have always been an exile, now I am no longer one: whilst waiting for Spain to be able to welcome me back, the French Communist Party have opened their arms to me, and I have found there all whom I respect most, the greatest thinkers, the greatest poets, and all the faces of the Resistance fighters in Paris whom I saw and were so beautiful during those August days; again I am among my brothers.

Читать дальше