Thus, on a psychological level, the problem is a similar one to that of finding a subject, of finding the apt vehicle for self-expression. Picasso finds himself in women — and the fact that he has otherwise been so isolated must have increased this need. Through himself, found in woman, he then tries to say things as an artist. Sometimes these things are unsayable because they are essentially outside the scope of the relationship. When they are about the essence of that relationship, when the shared subjectivity that Picasso needs is actually created by sex, then the results are purer and simpler and more expressive than any comparable works in the history of European art. Other works may be more subtle because they deal with the social complexities of sexual relations. Picasso abstracts sex from society — there is no hint in the bronze head or The Nude on a Black Couch of the role of a mistress, the happiness of marriage, or the attraction of les fleurs du mal . He returns sex to nature where it becomes complete in itself . This is not the whole truth but it is an aspect of the truth of which no other painter has had the means or courage or simplicity to remind us.

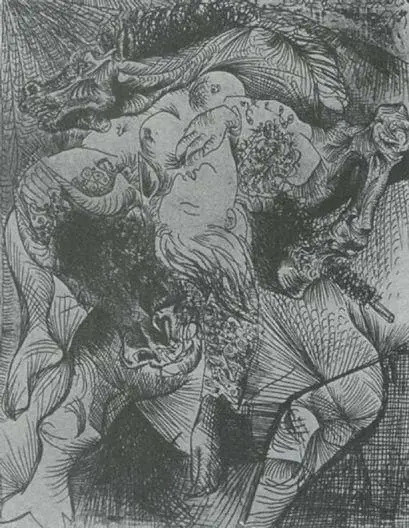

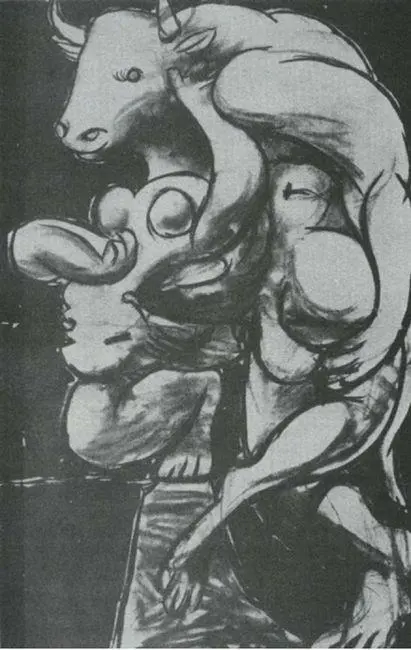

95 Picasso. Young Girl and Minotaur. 1934–5

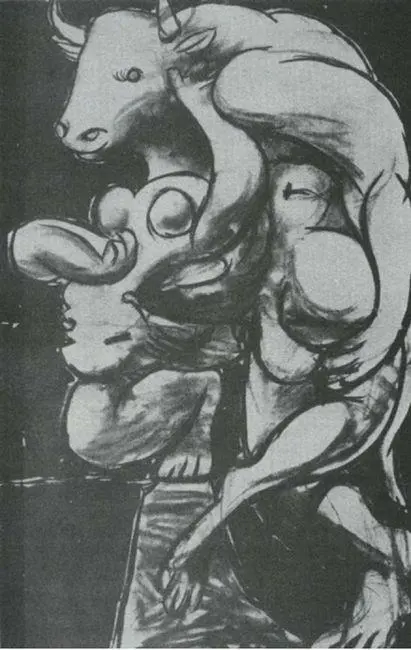

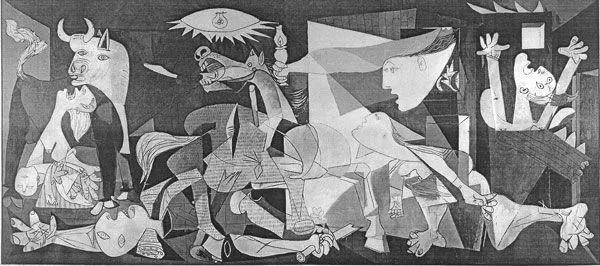

96 Picasso. Guernica. 1937

On 26 April 1937 the Basque town of Guernica (population 10,000) was destroyed by German bombers flying for General Franco. Here is the report from The Times :

Guernica, the most ancient town of the Basques and the centre of their cultural tradition, was completely destroyed yesterday afternoon by insurgent air-raiders. The bombardment of the open town far behind the lines occupied precisely three hours and a quarter, during which a powerful fleet of aeroplanes consisting of three German types, Junkers and Heinkel bombers and Heinkel fighters, did not cease unloading on the town bombs weighing from 1,000 lb. downwards.…The fighters meanwhile flew low from above the centre of the town to machine-gun those of the civilians who had taken refuge in the fields. The whole of Guernica was soon in flames except the historic Casa de Juntas.…

In less than a week Picasso began his painting. He had already been commissioned by the Spanish Republican Government to paint a mural for the Paris World Fair.

In June the painting was installed in the Spanish building there. It immediately provoked controversy. Many on the left criticized it for being obscure. The right attacked it in self-defence. But the painting quickly became legendary and has remained so. It is the most famous painting of the twentieth century. It is thought of as a continuous protest against the brutality of fascism in particular and modern war in general.

How true is this? How much applies to the actual painting, and how much is the result of what happened after it was painted?

Undoubtedly the significance of the painting has been increased (and perhaps even changed) by later developments. Picasso painted it urgently and quickly in response to a particular event. That event led to others — some of which nobody could foresee at the time. The German and Italian forces, who in 1937 ensured Franco’s victory, were within three years to have all Europe at their mercy. Guernica was the first town ever bombed in order to intimidate a civilian population: Hiroshima was bombed according to the same calculation.

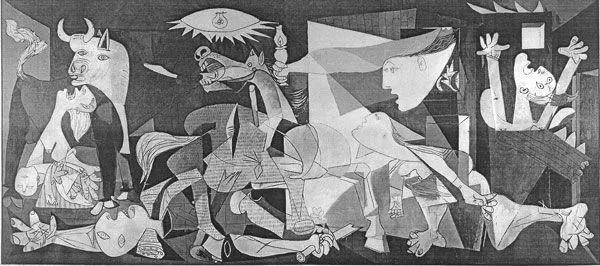

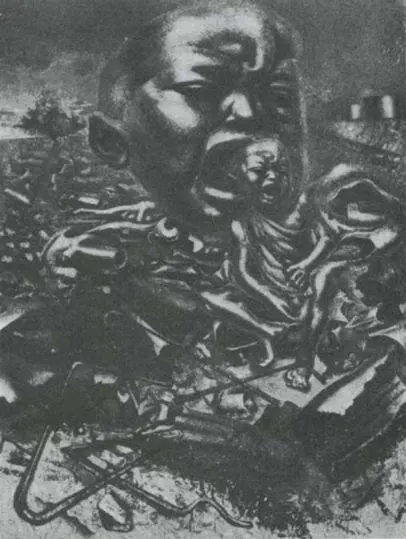

Thus, Picasso’s personal protest at a comparatively small incident in his own country afterwards acquired a world-wide significance. For many millions of people now, the name of Guernica accuses all war criminals. Yet Guernica is not a painting about modern war in any objective sense of the term. Look at it beside David Siqueiros’s Echo of a Scream , also painted in 1937 and suggested, I suspect, by a picture of a child screaming in a Spanish Civil War news-reel.

97 Siqueiros. Echo of a Scream. 1937

In the Siqueiros we see the materials which make modern war possible, and the specific kind of desolation to which it leads. By contrast, the Picasso might be a protest against a massacre of the innocents at any time. Picasso himself has called the painting an allegory — but has not fully explained the symbols he has used. This is probably because they have too many meanings for him.

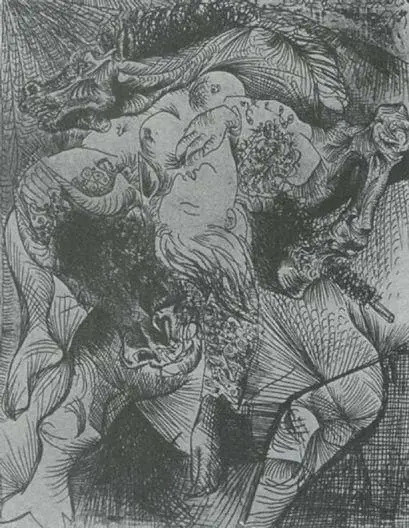

Three years earlier Picasso made an etching of Bull, Horse, and Female Matador , which, in imagery, is very similar to Guernica . But here the matador is Marie-Thérèse, and the meaning of the scene is wholly concentrated on the movable frontier between sexual urgency and violence, between compliance and victimization, pleasure and pain. That is not to suggest that it is complicated in anything but a sensuous way. It is the body, not the mind, that submits to a kind of death in sex, and an awareness, after love, of feminine vulnerability is the result of an instinctual impulse — an impulse which man shares with many animals.

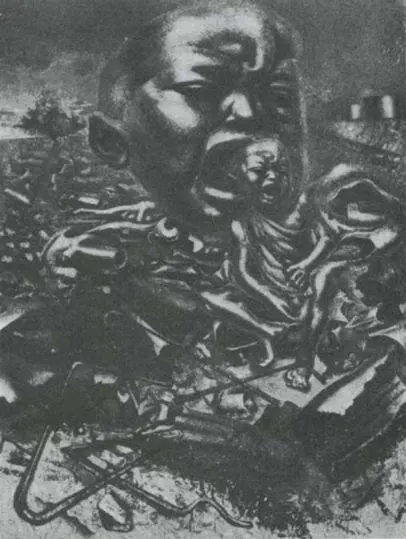

98 Picasso. Bull, Horse, and Female Matador. 1934

When Picasso painted Guernica he used the private imagery which was already in his mind and which he had been applying to an apparently very different theme. But only apparently — or anyway, only superficially different. For Guernica is a painting about how Picasso imagines suffering; and just as when he is working on a painting or sculpture about making love the intensity of his sensations makes it impossible for him to distinguish between himself and his lover, just as his portraits of women are often self-portraits of himself found in them, so here in Guernica he is painting his own suffering as he daily hears the news from his own country.

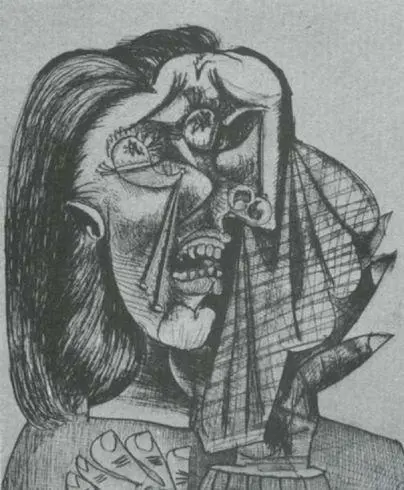

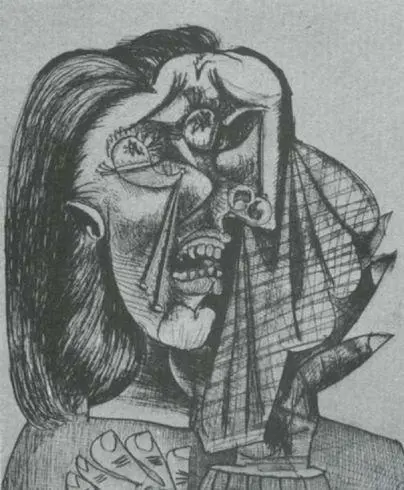

99 Picasso. Crying Woman. 1937

The etching the Crying Woman (which is part of the whole cycle of works connected with Guernica ) is no longer a directly sexual metaphor, but it is nevertheless the tragic complement to the giant bronze head. It is a face whose sensuality, whose ability to be enjoyed, has been blown to pieces, leaving only the debris of pain. It is not a moralist’s work but a lover’s. No moralist would see the pain so self-destructively. But for the lover, there is still a shared subjectivity. What has happened to this woman’s face is like a castration.

Guernica , then, is a profoundly subjective work — and it is from this that its power derives. Picasso did not try to imagine the actual event. There is no town, no aeroplanes, no explosion, no reference to the time of day, the year, the century, or the part of Spain where it happened. There are no enemies to accuse. There is no heroism. And yet the work is a protest — and one would know this even if one knew nothing of its history. Where is the protest then?

It is in what has happened to the bodies — to the hands, the soles of the feet, the horse’s tongue, the mother’s breasts, the eyes in the head. What has happened to them in being painted is the imaginative equivalent of what happened to them in sensation in the flesh. We are made to feel their pain with our eyes. And pain is the protest of the body.

Читать дальше