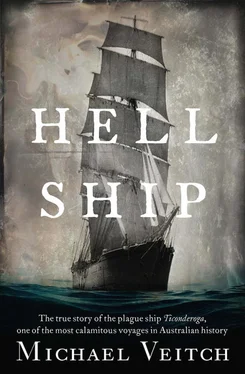

Far from being a destitute Highlander, McKay was travelling to Melbourne to take up the role of Vice Principal of the newly established boys’ school, Scotch College, and boarded the Ticonderoga with his wife Margaret and five children, the youngest aged two. According to his grandson, Frank McKay, it had not been an easy decision and in a brief history of the family, he describes ‘the many heart searchings before Charles McKay made the big decision to take his family to Australia and start a new life in a new world’. [6] Personal notes of Frank McKay, care of Nepean Historical Society

The shipboard lessons over which McKay presided were usually rudimentary in nature, offering basic instruction in English, reading, writing and simple arithmetic. For some of the children, however, these were of a higher standard than anything they had experienced at home, and for others it was their first taste of schooling altogether. A fair proportion of the adults, many of whom could neither read nor write themselves, likewise took advantage of McKay’s instruction, picking up vital skills such as the writing of their own name, as opposed to the leaving of just a simple mark. Also listed as a sexton of a Presbyterian church—that is, one who has responsibility for the grounds and graveyard—McKay ‘would minister to the spiritual needs of the Highland passengers by conducting services in Gaelic. This he did throughout the voyage, as well as after landing on the station’. [7] Personal notes of Frank McKay, care of Nepean Historical Society

At the rear of the ship were the single women’s quarters, presided over by another of Patey’s appointments, the single women’s matron. According to the descendants of passenger Janet McLellan, the Ticonderoga ’s matron was 38-year-old Miss Isabella Renshaw. It was into Miss Renshaw’s care that the precious key to the single women’s quarters was entrusted, which she used on a nightly basis to lock the girls in, preventing any illicit after-hours liaisons forming between them and the single men, or the crew. In the morning, they would begin their lessons in reading, arithmetic and Bible studies. Miss Renshaw was usually assisted by some of the abler and better educated girls, such as Annie Morrison from the Isle of Mull. Needlework and shirt-making were also taught, with the girls being able to keep the garments they made on the voyage.

Free time was allowed, and the sexes could in fact mix, but only on the open upper deck under the matron’s supervisory gaze. An obsession with women’s perceived ‘virtue’, particularly among groups of young and unattached females, was a feature of Victorian society, so it was replicated at sea. More than any other group on board the ship, all aspects of the young women’s behaviour, appearance and demeanour were constantly assessed and judged by passengers and crew alike, with ‘wantonness’ suspected as the motive behind many of their actions.

One of those girls who would have been under observation was 22-year-old Janet Blair, a Presbyterian from Argyllshire whose clan, fiercely independent Protestant Covenanters, had been all but wiped out in the ‘Killing Time’ of the religious wars with England in the late seventeenth century. Thanks to a detailed account penned by her granddaughter late in her life, Janet Blair’s personal story survives.

The eighth of fifteen children, ten of whom survived, Janet grew up on a farm of 320 acres on Loch Fyne in Scotland’s west. When she was fifteen, ‘the fever’ took her father and two more of her siblings, at which point her older brother gave up the farm and moved with the rest of the family to Glasgow, where Janet became a housemaid to a wealthy family of gentlemen farmers from Argyllshire, the McPhersons. One of their three sons, Dugald, had become a successful sheep farmer in Australia and, impressed with the girl, Mrs McPherson began to encourage her to travel there herself to become Dugald’s housemaid. Wages and conditions for a girl such as she, reminded Mrs McPherson, were far better than she could ever hope to receive at home. As Dugald was unmarried, Janet declined. Her enthusiasm to travel was sparked, though, and she even managed to convince a brother, a brother-in-law and two of her sisters to make the journey with her. At the last minute, they all backed out. Undeterred, Janet continued alone, and at Glasgow was seen off on the ferry in a tearful farewell by several members of her family.

At Birkenhead, she joined many other single girls likewise seeking a new and better life, and on 28 July was one of the first to board the Ticonderoga , several days before she sailed, bringing along her prized possession, a fine three-door oak trunk with ‘Janet Blair’ painted in elegant lettering on the outside. She even brought her own cutlery, and—quite contrary to the regulations—a blanket and pillowslip, together with as much warm clothing as she could carry. The journey, she had been told, would involve heading into some cold and icy weather to the south. Just how icy would only become apparent in the weeks to come. Although travelling alone, Janet was soon to make a firm friend of Georgina McLatchie, listed as ‘Baptist’, 25, from Edinburgh. As the voyage began, the two young women could have no idea of just how much each would come to rely on the support of the other.

Although many of the appointed steward positions were officially voluntary, a small gratuity was nevertheless usually forthcoming. It is not known what the Ticonderoga ’s coffers offered, but a similar voyage taken a few years later on the emigrant vessel Atalanta, the schoolmaster and the matron were each paid £5, as were the galley assistants.

Perhaps the most important decision made about the Ticonderoga ’s nearly 800 passengers was their arrangement into the 125 or so ‘messes’ of around six people each, in whose company they would share the experiences and travails of the voyage. An initial division had taken place onshore while still at the depot, but the process was refined during the first few days at sea by the stewards in consultation with the surgeons and the captain. Where possible, the bunks of the respective members of each mess were situated close by one another, as was their allotted ‘desk’, a 5-feet-wide oak table with raised edges to prevent plates and other utensils falling to the floor with the roll of the ship. [8] Kruithof, 2002, p. 36

Space being what it was, several messes would in fact share the one desk, but it was within one’s mess that the passengers tended to mix, ‘as though each mess formed its own little village on board’, according to historian Mary Kruithof. [9] Kruithof, 2002, p. 36

The object of the messing system was to encourage shipboard harmony; hence people of the same town, village or county were, where possible, placed together. Particular care was also taken to avoid potential flashpoints arising from those eternal sources of discord, religion and politics. The long voyage would provide more than enough idle hours for arguments to fester and ideologies to erupt, and religion—ever a sore point throughout Europe—was particularly inflammatory in the context of Scotland and its recent brutal history with England. With an emigrant’s region and religion both stated on their form, those from opposing faiths, or people who had been observed to clash or squabble at the depot, were berthed as far from each other as possible. However, some may have been closer to their fellow passengers than they thought, travelling alongside distant members of their own large, clan-based families. There were, for example, three families each carrying the names Campbell, Herd, McKay and McPherson, four Camerons and no less than five separate families named McDonald. The names Bruce, Fraser, Morrison and several others were also represented multiple times among the Ticonderoga ’s passenger list.

Читать дальше