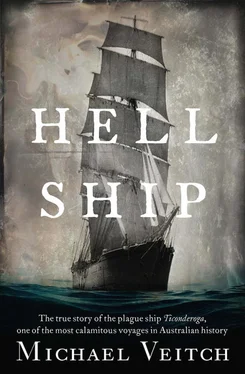

In all cases, the space between the bed boards of the top and bottom bunks was a claustrophobic 18 inches, slightly less with bedclothes, meaning that virtually any raising of the head was impossible. To the side, considerably less than an arm’s length away, was the neighbouring bunk, with the only privacy being provided by a flimsy board 23 inches in height, and affording no real modesty whatever. It was into these coffin-like dimensions that the Ticonderoga ’s passengers were confined every night, or when rough weather arose. Then, as with that first storm just hours after leaving Birkenhead, the porous nature of a wooden sailing ship was revealed. On that occasion, as well as many more to come over the next twelve weeks, sea water would regularly seep, drip and occasionally gush in torrents into the passengers’ living areas. Even on calm days, a wave or current could spring up unexpectedly and cascade in terrifying torrents down one of the open main hatches, making a river of the main and lower decks and soaking everything from clothing and foodstuffs to the bedding, whose straw interior quickly rotted and stank.

The Ticonderoga ’s flushing water closets were indeed innovative, but at night or during a storm, they were difficult if not impossible to access, particularly for women in the voluminous skirts of the day who had to contemplate often two sets of ladders in virtual darkness. Instead, utensils of any kind were used to catch urine and other waste, and these often spilled with the movement of the ship. The smell of human beings permeated the whole ship. Sweaty clothes could only be washed sporadically, and then only in seawater tanks on the upper deck, fresh water being strictly reserved for drinking and cooking. Whale oil lamps in their braces nailed to the walls gave off at least some little light, but exuded a particular pungency of their own. Added to this was the stench of the rats—impossible to eradicate even in the newest vessels—as well as the cats assigned to catch them and their many associated stinks. Then there were the babies. Dozens upon dozens of vomiting, nappy-filling infants and toddlers crawled and cried all over the Ticonderoga. Their numbers in fact would be added to during the voyage, as pregnant women who had boarded at Birkenhead contributed no less than nineteen births at sea. It was said that the Ticonderoga ’s crew, upon opening the hatches every morning, reeled back at the revolting miasma rising up from the decks below. [2] Kruithof, 2002, p. 46

Later in the voyage, when the ravages of disease took hold of the ship, the stench would defy description.

Initially, though, as the Ticonderoga tracked far out into the Atlantic, a shipboard routine of sorts began to develop, with perhaps the greatest initial shock for people accustomed to the quietness of small village life being the sudden avalanche of noise on board a large and crowded sailing ship. The hundreds of voices of the passengers—talking, arguing, breaking wind, vomiting, copulating, snoring, all in alarmingly close proximity; the constant shouts and swearing of the crew and the officers; the babel of children yelling, playing, crying; then the array of sounds emanating from the ship itself. As soon as the Ticonderoga left the heads of the River Mersey, her timbers began their endless heaving, whining chorus as she began to be pulled and twisted by the elements. Even the clawing hiss of the sea seemed to be conducted upwards through every board and every beam, amplified in the limited confines of the ’tween decks. In a storm, the noise would come crashing from above in terrifying bouts, as if the ocean itself—like a monster at the door—was attempting to batter its way in. Then there was the continual jangling of chains, sails and rigging; the thumping of feet on the decks above; the wind playing its perpetual symphony through the rigging. It all combined to make the Ticonderoga ’s aural landscape a blaring, multi-layered cacophony.

The one sound that governed the rhythm of people’s lives on board, however, rang out from the ship’s bell. Like the regulator on a gigantic clock, it was this brass voice that spoke the routine of life on the long journey. The bell sounded for the passengers to rise at 7 a.m., then at the other end of the day, at 10 p.m., to go to bed. It began the ship’s day, not at midnight but at midday ceremony, as the captain and mate lowered their sextants at the sun’s zenith and Boyle uttered, ‘Make it noon, first mate’, and then the response ‘Ay ay Captain’, as the bell was struck two times in quick succession. Then, the timeglass was turned for the sand to run exactly 30 minutes, at which point the bell would be struck once to sound the half hour, and the glass turned again. So this would continue, day and night, throughout the life of the voyage.

The bell also signalled religious services (of which there were many of various denominations), heralded announcements of news or decrees from the captain or the stewards, and alerted people to go below in the face of impending weather. Most of all, it drove the pulse of shipboard life: the daily meals, around which all other activities revolved.

Captain Patey and his officials at the depot had taken considerable care in appointing from the Ticonderoga ’s passengers the important roles of stewards and constables, who would manage various necessary tasks, such as the messing and meal arrangements, conducting educational lessons, and to assist the ship’s surgeons in maintaining levels of hygiene and cleanliness—a concept quite alien to some (and which, in the Ticonderoga ’s case, would eventually prove impossible anyway). Nurses were likewise appointed to work in the two hospitals, particularly those whose written form demonstrated some prior medical or nursing experience. Among these were John and Mary Fanning, Presbyterians from County Coleraine near Londonderry in Ireland, travelling with their daughters, Mary and Catherine, and son, Patrick. Mary was listed as a midwife, a respected position in Irish society, and one of only two female professions to be listed in church records, the other being ‘nun’. [3] Kruithof, 2002, p. 48

Mary was thus asked to work as a nurse in the women’s hospital while John was requested for the men’s. Both readily accepted. The other skill of the Fannings was their knowledge of the Scots-Irish dialect, closely related to the Gael of the Highland Scots themselves.

Recalling the voyage to a newspaper reporter in 1917, passenger Christopher McRae from Inverness, who travelled as a teenager with his family, wrote:

To carry out established rules and conditions imposed by the Captain and the Doctors, men suitable were elected to act as constables or stewards—the names of two of them I still remember—one being Andrew Dempster, a single man. The other—a young married man named Douglas Rankin. There were many others. [4] Letter written by Christopher McRae in 1917 addressed to Mr Kendall, Officer in Charge, Quarantine Station Point Nepean, held in the collection of the Point Nepean Historical Society, Sorrento, Victoria.

Galley assistants had also been appointed to help the cooks, along with attendants for both the male and the female hospitals. Then there was the important role of ship’s schoolmaster, who would provide daily lessons for the numerous children—and some of the adults—on board. This fell to 46-year-old Charles McKay who, as a professional teacher and a graduate of Aberdeen University, was one of the most educated of the Ticonderoga ’s passengers, and who also happened to be fluent in the Highland tongue, Gaelic. [5] Personal notes of Frank McKay, care of Nepean Historical Society

Christopher McRae believed him to be one of the most important figures on board the ship.

Читать дальше