Apart from the food and provisions, the Ticonderoga also had to take on board utensils and galley supplies for around 800 people who would be dining in 126 ‘messes’, around the large wooden tables installed along the two covered decks adjacent to their bunks, and in fine weather, even on the open upper deck. In their hundreds, serving plates, bread baskets, butter dishes, water beakers and some more curiously listed items such as 246 ‘tin pots with hooks’ and 126 ‘potato nets’ were all included.

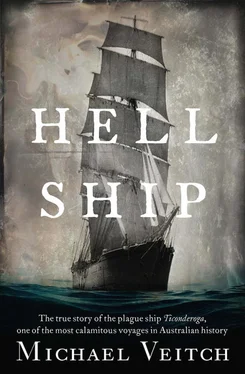

The list had been worked out meticulously, checked and inspected by Captain Patey who, to the relief of Mr and Mrs Smith, was pleased with what he saw. He needed to be meticulous. There would be no chances at replenishment of anything along the way. The Ticonderoga ’s route, following the so-called Great Circle around the bottom of the world, would make not a single stop along the way. The next land her passengers would touch after departing the shores of Britain would be Australia. Anything that was not taken aboard at Birkenhead, the passengers and crew would have to do without.

In the late July heat, crew men had worked with the longshoremen on the wharf, assembling the mass of provisions and carefully arranging them like a gigantic three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle inside the gloomy hold and, using the ancient art of the stevedore, spreading the load so as not to upset the clipper’s delicate trim.

On the first day of the new month of August, the long process of embarkation began. No matter how long this moment had been contemplated, and despite the months—even years—of anguish, the agonising decision making, the advice taken, the information absorbed, the long procession of farewells and last-minute regrets, nothing could prepare the Ticonderoga ’s passengers for the totally alien environment they were now to enter. As they prepared to take leave of the Birkenhead depot, harried staff shouted names from lists as anxious parents formed lines and wrangled their excited children. In small groups, divided into nationalities, then into their respective messes, the passengers were marshalled in a great shuffling line towards the waiting ship.

Queues stretched back from the wharf to the depot as families tried to keep themselves and their luggage together, snaking towards the great black wall of the Ticonderoga ’s hull ‘like Noah and his Family going into the Ark’, as one departing passenger observed. [4] Charlwood, 1981, p. 87

Several brass bands had been hired for the occasion and stood on the wharf belting out favourites like ‘Home Sweet Home’, ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’ and, of course, ‘Rule Britannia’. [5] Charlwood, 1981, p. 94

With deck space on board at a premium, each person had been issued with two canvas bags into which they were told to pack only the clothing they would need for the voyage; the remainder was to stay in their boxes and trunks, which the crew had already stowed into the holds. After a month at sea, one box clearly marked ‘wanted on the voyage’ would be brought up to the upper deck for another month’s clothing to be taken out and exchanged, with the dirty clothes being packed away. Almost nothing except food would be provided once on board, so every essential item, from children’s nappies to cooking utensils, had to be carried by the passengers and stowed in the lockers under the already less than spacious bunks.

The ship’s deck was alive with the crew, who seemed to crawl over every inch of her. Heads craned up to the top of the main and mizzen masts, where men could be observed high up in the spars and top masts checking and rechecking lines, shrouds and braces. Even tied up and beside the wharf, it seemed a dangerous place for anyone to be. What it must be like up there at sea and in rough weather was beyond imagining. Not that it appeared to concern them, as the crew’s singing—both their work songs and traditional tunes of departure—rang out jauntily over the bulwarks.

More names were checked off more lists as passengers emerged onto the rickety gangplank, which felt more than unsteady under their feet. Then, setting foot for the first time on the upper deck, the line snaked down one of the hatches, which opened like a dark, gaping maw. Helped by one or more of the Ticonderoga ’s crew, it was at this moment that her passengers were introduced to the crowded and claustrophobic underworld that would be their home for the next three months.

Some gasped as they ducked their heads at the entrance to the main deck, adjusting their eyes to the sudden darkness. Some gagged at the already strange mixture of smells of cut timber, whitewash and hot tar, as well as a strange, earthy smell left from the thousands of cotton bales that had been crammed into her from her previous incarnation as a cargo vessel. Some felt instant claustrophobia clawing at their chests. Embarkation staff and members of the crew, harried and impatient, saw them as quickly as possible to their assigned bunks then left them to stow their possessions in the small lockers as they attended to the next passenger. Panic about the tiny space in which they were expected to live over the coming months was experienced by many. Others were directed to proceed even further into the ship, down yet another gaping gangway to the Ticonderoga ’s lower deck, feeling as if they were descending into a mine. The same thought crossed each of their minds as they lowered themselves and their families down into the hold: how could we ever get out of here in a hurry?

Another hour or so of settling in, and 795 passengers plus several dozen crew, including officers, able and ordinary seamen, several cooks and carpenters, [6] Kruithof, 2002, p. 40

settled themselves into the spaces and crannies of the great ship. The noise of dozens of families and children and the shouted orders of the crew reverberated around the confined spaces in a cacophony of tongues and accents. The mood of the passengers varied, from the quiet anxiety of the mothers with children to the enthusiasm of the young, single men who—like young, single men everywhere—looked forward to what they saw as a great adventure on the way to wealth and good fortune in the far-off colonies. Already, they had begun to think of themselves as expert seamen.

Two men had already established themselves on board the Ticonderoga who were neither passengers nor crew, but who occupied a unique position somewhere between. It could be argued that theirs was one of the most important positions on the entire ship. It was upon the shoulders of these two men that the health and happiness of the passengers on the long voyage would rest. Already they had begun making the rounds of the decks, reacquainting themselves with passengers they had met during the medical inspections at the depot a day or two earlier. Together, they presented an unshakeable front of authority and good cheer as they patted the heads of some of the children, uttered reassuring words about the strength of the ship and the capable hands and experience of Captain Thomas Boyle and generally set a tone of calm. Of all the ship’s officers, it was these two men with whom, over the weeks to come, the Ticonderoga ’s passengers would become most familiar—for better and for worse. Over time, their roles would evolve from offering comfort and advice, and attending to minor health concerns and daily grievances, to those of warriors in a life-or-death struggle. They were the Ticonderoga ’s two official surgeons, duly appointed by the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission, the seasoned and respected Dr Joseph Charles Sanger, 48, and his assistant, a younger man with a broad and steady face, Dr James William Henry Veitch, 27.

Finally, early in the afternoon of Wednesday, 4 August 1852, the ship’s bell was struck to alert all those not travelling to depart the ship and groups of friends and well-wishers made their way towards the gangway, tears springing to their eyes, as well as those of the people about to depart. Then, as if announcing the arrival of an emperor, the bell tolled again to signal that the Ticonderoga ’s master, Thomas Boyle, was coming aboard.

Читать дальше