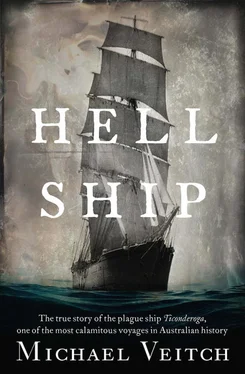

Strangely, no image exists of the Ticonderoga —not a painting, photograph or even a sketch has survived to give us a picture of how she would have appeared. This is unusual, as many paintings—even photographs—exist of earlier vessels, and particularly considering that the Ticonderoga was said to be a most beautiful ship, attracting much interest among ship-savvy populations wherever she went.

Her fame spread even to London and, despite never once visiting the capitol, the popular Illustrated London News published an article on her, featuring a detailed cut-away diagram of her internal decks and layout but no actual image of the Ticonderoga herself. The story appeared shortly before she sailed and also described in great detail the work and function of the Birkenhead depot, providing several graphic illustrations of the buildings and the placement of the passengers therein. As for the ship herself, we are left only with educated assumptions as to her appearance. The British-built Alnwick Castle , at an almost identical tonnage and similar dimensions, is believed to have borne a striking similarity to the Ticonderoga.

This is not the only area of mystery surrounding the Ticonderoga and her infamous Australian voyage. Her exact tonnage is vague, as is the number of masts she carried, with as many sources citing three masts as four. Exactly how many passengers she carried to Melbourne is also a matter of contention, as well as her precise arrival date in Victoria, and even the numbers who died on board the voyage and later in quarantine. This vagueness somehow contributes to the everlasting notion of the ‘ghost ship’, as witnessed by the two local lime-burners as she entered Port Phillip Bay at the end of her disastrous run in November 1852.

Defining the Ticonderoga ’s tonnage is in fact far from academic, as it was this that determined the number of passengers she was permitted to accommodate on her two very crowded decks on her trip south to Victoria. The number varies not only from source to source, but across the often bewildering definitions that varied between countries, particularly between the United States and Britain. The tonnage of the Ticonderoga would initially have been determined by the ancient Builder’s Old Measurement, expressed in ‘tons burden’, a calculation based on a ship’s length and maximum beam. This system was applied inconsistently, and was in any case considered unreliable, particularly as the ships of the mid-nineteenth century began to increase significantly in size. It was not until 1854 that Britain’s Board of Trade introduced a single method for the measuring of ship’s tonnage, the Moorsom System, based on dividing the ship’s internal volume by 100 cubic feet (2.8 cubic metres) then subtracting internal machinery and structure to arrive at a more workable figure. Even so, the tonnage of the Ticonderoga fluctuates across ‘registered’, ‘registered gross’, ‘net registered’ and so on to between 1089, 1280 and even up to 1514 tons.

There are, however, many facts about the Ticonderoga that are not in dispute. At 169 feet long, she was by no means the biggest of the Yankee clippers, with some sources even referring to her as a ‘semi-clipper’. By way of comparison, the Marco Polo, which made the same journey shortly before the Ticonderoga with Bully Forbes in command, was 14 feet longer at 183 feet and the great Stag Hound , at 226 feet, was larger again. But by all accounts, the Ticonderoga was a particularly fine-looking vessel with graceful, even delicate lines. She was built of copper-sheathed oak and her hull was painted jet black, with a fine white stripe running its length, framing the even row of wooden scuttles that ran from bow to stern. She was 37 feet wide, had a draught of 18 feet and her stowage capacity was enhanced by a feature not obvious upon initial observation: an extra deck. Many clippers were single-deck ships with an open, cavernous storage area, whereas the Ticonderoga ’s extra lower level made her suitable for a variety of uses, such as the transport of emigrants. Word of her fine lines and construction went around the already ship-obsessed population of Liverpool, who are said to have come down in their droves to see for themselves the beautiful American clipper with the long and unusual name, and offer their opinion on her pedigree.

Little is known about the Ticonderoga ’s early life. It appears she went to work immediately upon her launch in 1849, running back and forth across the Atlantic, her holds bursting with bales of cotton from America’s southern states, destined for the mills of the English midlands. To enhance profit on their return journey westward to America, her crew would install bunks and mess tables (known as desks) and take on a load of privately paying passengers—many of them Irish—searching for a new life in a country that was not part of the loathed British Empire. In 1852, the year she sailed to Melbourne, she had already completed two Atlantic crossings, arriving in New York on 22 April with 300 passengers, then executing a quick turnaround with a load of cotton to arrive back in Liverpool by late May. A considerable quantity of stores were left over from one of these Atlantic runs, which were then utilised on the trip to Australia.

Her captain and part-owner was 30-year-old Irish-born Thomas Boyle, who installed his brother William as third mate and purser. A third Boyle, J.H. Boyle, appears to have been employed as the officer in charge of overseeing the provisions of the ship for her voyage to Australia, but his relationship to Thomas and William, if any, is unknown. One of several misconceptions regarding the Ticonderoga is the notion that she had previously served as a cattle transport. Her extra deck would appear to have been suited to the task of accommodating several hundred live beasts in hastily erected stalls, and some have even pointed to this as the source of the disease that later ravaged her. Several former passengers later mentioned this supposed episode in the ship’s history in letters and recollections, but researchers have discounted it as a rumour, its origins now forgotten in time. Perhaps cattle spreading disease was an easier notion to accept than it having been brought on board by the passengers themselves.

From a crisis to find enough able bodies to rescue the 1852 Australian wool clip, the British and colonial governments now found that there were not enough ships to carry the deluge of those who suddenly wanted to go. Everyone, it now seemed, was determined to participate in this ‘great race’ south to Victoria to make their fortune before—as they had seen happen in California—the gold started to peter out. The statistics speak for themselves. In 1850, just over 16,000 emigrants, both assisted and private, made their way to Australia from the United Kingdom. In 1851, that figure jumped to 21,532. However, 1852 saw an extraordinary increase to 87,881 people leaving for Australia, making it the highest in the 50-year period between 1830 and 1880. [1] Pescod, 2001, p. 193

The Board, for years having done its best to spruik the benefits of Australia with limited success, now found that it was swamped with applicants, and the ships it had previously relied on to transport its assisted emigrants were no longer available. These had long departed, scattered across the world’s oceans, having filled their berths with the far more prosperous class of private passengers willing to pay their own way and delivering the shipowners a much larger profit per head.

The Board now scrambled to find new ships. In 1850, to increase passenger numbers, the relative luxury of a private cabin—for those few passengers able to afford it—was abolished, with everyone now corralled into the single class of steerage. They soon found, however, that few shipowners were interested in applying for the assisted emigrant trade when better-paying private passengers were willing to fill their berths. In Liverpool alone, shipping lines were struggling with a waiting list of over 7000 unassisted emigrants, having already shipped 6000 over the previous twelve months. Pressure came from the other side of the world too, as the Board’s agent in Melbourne now recommended that vessels of no less than 800 tons be hired to bring over much larger numbers of the kinds of people who were not likely to head straight to the goldfields as soon they set foot on the wharf. The Board therefore had little choice but to look to a class of ships previously uncontemplated: those big, fast, twin-deck ‘extreme clippers’ of America.

Читать дальше