Skip Henderson, Bywater Bone Boy

“Katrina will never be over. Not until the last person moves back. Not until the last X is off the last house,” he answered, melodramatically. After all, Skip knew that for every one resident who’d returned since the storm, two had stayed in Houston or Atlanta. As for the X ’s, the so-called Katrina tattoos painted by the National Guard during their body search, several residents, certainly those in Bywater, were keeping them as souvenirs. Many of the new people regarded the tattoos as badges of honor, hard-to-come-by authenticity in an ersatz era. At the end of Montegut Street a sculptor had enshrined his building’s X in bronze. You wanted one on your house, just in case the angel of death came this way again. The marks had become part of the city, like the storm itself, one more personality-building scar.

What Skip really wanted to know was what I was going to do with the lampshade; it was still half his, he had a right to know.

“If you’re not going to bury it, then what?” Skip half pleaded. “What?”

We were in the cathedral now, the mass under way, the priest quoting Genesis 3:19: “For dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.” It was as Skip always said: there could be no Fat Tuesday without Ash Wednesday, the gorging of carnival being incomplete without the spare reminder of life’s fleetingness. The bead-decked yahoos drinking themselves into oblivion on Tuesday who didn’t show up to mass on Wednesday, whatever religion they were, were clueless as to the real meaning of Mardi Gras.

The lines to receive the ashes were long, probably twice as long as in the past couple of years, another sign that the town, the Big Easy once more, was back and open for business. It was going to take Skip at least twenty minutes to receive the sacrament. This gave me plenty of time to think things over, which was a good thing because I like to be in churches, especially ones as handsome as St. Louis Cathedral. It is good to be surrounded by the sacred mumbo jumbo, especially when it isn’t your sacred mumbo jumbo. Sitting in a temple, even a fancy momma like Emanu-El in Manhattan, was never so relaxing. In temple there were issues, questions of childhood, history, tradition, faith. In church none of that applied. Whatever was stirred up here was Skip Henderson’s problem, not mine.

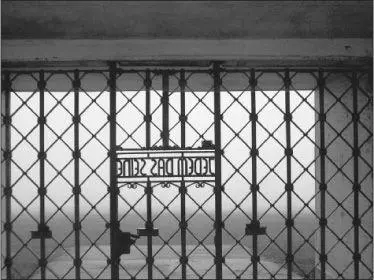

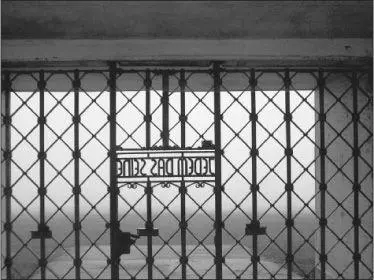

The lampshade had opened a special portal, all right, I thought, recalling a story told to me by Plater Robinson, who ran the Holocaust education seminars at Tulane. It was about Henry Galler, a New Orleans Holocaust survivor and longtime proprietor of Mr. Henry’s tailor shop on Jackson Avenue. Henry and his wife, Eva, also a survivor, were forced to evacuate to Dallas during Katrina. They lost almost everything, including a piece of soap Henry said he’d gotten at the concentration camp. Soap supposedly made from Jews, kept all these years, dissolved in the flood.

The connections piled up. One morning I heard from Shiya Ribowsky, who sounded excited. Most of the time, if you ask Shiya how well he sang at Shabbos services, he’ll say he was awful, that he had a head cold or phlegm in his throat, something that kept him from being the greatest cantor west of Galicia, which, in his heart, he knew he was. This past Shabbos, however, Shiya said, “I was on. Smoking.” After the service ended, a large black man “with these gigantic biceps” came up and shook his hand. “Really dig your music, man,” he said.

“I didn’t know who he was,” Shiya said. “We have some black congregants, six or seven, but I’d never seen him before. Then he tells me he’s Aaron Neville. He came over to the shul with a friend. I said, ‘Well, thanks, dig your music, too.’”

I’d even talked to David Duke from time to time, most memorably on the morning after the 2008 election. He was driving to Memphis to address a long-planned convention of his “white rights” group, the European American Unity and Rights Organization (EURO), and I asked him what he thought of the presidential results. “It is an Obamanation! It is the nadir of the country. The end of America as we know it,” Duke said before shouting, “My God, I think my front tire is coming off. I’m going to have to call you back.”

After receiving the German FBI report on the lampshade, I called Volkhard Knigge to tell him I’d pretty much decided not to bury the lampshade. “This is the way it is with these kinds of objects; a historian is always lingering between the realm of hope and disappointment,” Knigge said, with the curious cadence that sometimes made him sound like he was talking in an ethereal blank verse. “You are forced to accept the idea of limits. There are things you will never know. It can be frustrating to be confronted by these structures of silence and the fantasies they produce. This is why it is helpful to be organized in your approach, to establish frameworks for thought.

“With this lampshade you can say it had a first history, which is that identification with the Buchenwald camp and people like Ilse Koch. The lampshade on the Table with people passing by. Then there is the second history. The history with you. Your adventures and your thoughts. There is the strange and frightening idea that someone would make a lampshade out of a person and it has arrived in New Orleans after a storm. This interests you, so now the first history becomes infused by the passage of years and a new context. Then we would come to a third possible history, one we cannot guess. Who gives us the right to close the book for the future? The questions must be kept open. The best thing to do is treat it with respect, and we will see what happens next.”

That was probably good advice, I thought. If the lampshade was a story, I was only writing one part of it. The thing would continue on, like the line of people waiting to have a bit of ash smeared onto their forehead. It would stay in the world, as it should. Someone would find it again.

Writing this book has been a disturbing but rewarding experience. The goal was to look at a frightening object from as many angles as possible and try to make sense of it. But you have to start somewhere, and that would be with Skip Henderson. As noted, I’ve known Skip for some time, but our friendship was probably always pointed toward the moment he purchased the lampshade from Dave Dominici. It is something about Skip: He has the air of destiny about him. No one else I know could have found the lampshade and known, immediately, of its importance. His sensibility, however cockeyed, informs these pages.

This said, to write such a book—or rather to simply see it as a book that could be written—one needs early supporters, trusted fellow travelers who know you, know what you can do, what fears you must confront to do good work. I have been lucky in this regard to have friends like Michael Daly; my longtime running mate Jonny Buchsbaum; Lou DiBella, the world’s greatest Harvard-educated boxing promoter; the nonpareil Steve Earle; and the fabulous Zarela Martínez (whose hospitality and margaritas were most welcome).

Encouragement is nice, but one cannot proceed without a more tangible kind of faith offered in the form of business acumen and a checkbook. I consider myself very fortunate to be a client of my agent, Flip Brophy, of Sterling Lord Literistic. Flip knows a good idea from a bad one and doesn’t mind telling you so. Flip deserves credit for demanding we take this idea first to David Rosenthal, then the grand poo-bah at Simon & Schuster. I knew David would understand what I was hoping to accomplish. We have, after all, done business before, coming up together through the old magazine jungles of the 1970s. He was very smart then, even smarter now, but still very hamish , certainly for a poo-bah.

Читать дальше