He nodded.

“Then they had these other people, marching by. And I think I saw that thing you’re talking about—a lampshade they said was made of human skin. That was really scary.”

“You’re talking about footage from Buchenwald. The Buchenwald concentration camp,” I said.

“Some concentration camp, that was for sure,” Cyril answered. “Long as I live I’ll never forget those pictures. Gives me the chills thinking about it even now. Because there’s two things about seeing that movie that have always stayed with me.

“First of all, I couldn’t believe white people would do that to other white people. But even more than that was the question about why they picked that particular Wednesday to show that particular movie to us—the kind of message they were trying to send.”

ELEVEN

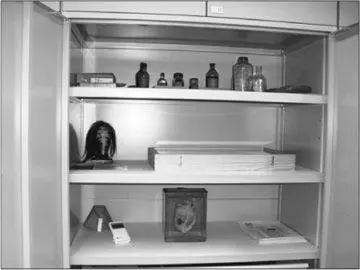

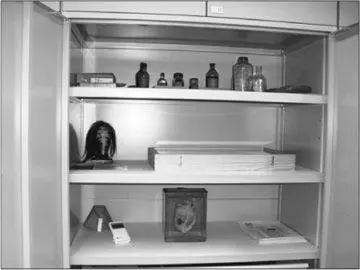

Herr Wolfgang Röll put on his white cotton gloves, turned the key in the gray metal door, and opened the cabinet. The main museum at Buchenwald was several hundred yards away, down the hill from the Appellplatz . But these objects, kept in the temperature-controlled cabinet inside the former SS barracks that now served as the administration offices of the Buchenwald Memorial, were “separate.” They were “not for public view,” Herr Röll told me as he carefully placed the items on the table between us. There was a cardboard box of tapered vials from the Serum Institute, part of the Department of Epidemic Typhus and Virus Research run by Waffen-SS doctors in camp blocks 46 and 50. In one research experiment, twenty-one of the thirty-nine prisoners tested died, which added up to, as dutifully noted in the final report, 55.5 percent of “the control group.” There were also some human body parts floating in formaldehyde, a shrunken head, and a lampshade.

The lampshade was small, probably a third the size of the object found in New Orleans, and it was crudely made, the diminutive panels stitched together with thick rawhide on a metal frame. It was grayish in color, with darker blemishes in a scattershot pattern. It was thick and bumpy to the touch. It felt inert, without animation.

“This is a fake,” I told Herr Röll.

Röll smiled. “Yes,” he said.

“It is plastic or some laminated paper.”

“Yes. Quite fake.” Röll smiled again, a knowing but somehow inscrutable smile. “But it wasn’t always fake. Once it was real. Or at least that’s what was said. In the GDR times, much was said about lampshades and everything else.” [21] For a discussion of anti-Semitism in the German Democratic Republic and issues of right-wing activity in the current Germany, see the work of the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, http://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/start .

Herr Röll’s cabinet

A few nights earlier, in Berlin, I’d been out to dinner with some friends who had grown up in the German Democratic Republic, aka GDR, or East Germany. They told me about the lampshade in Herr Röll’s cabinet.

“It was something they always showed you when you went on school field trips,” recalled Anetta Kahane, who was born in East Berlin in the early 1950s into an illustrious German Jewish family. Her father, Max Kahane, fought in the Spanish Civil War on the loyalist side, which was considered the gold standard of heroism in the stridently antifascist cosmology of the GDR state. Max later became head of the official GDR news service. Anetta’s mother, Doris, a well-known state-sponsored painter, was the niece of Victor Klemperer, author of the famous diaries detailing his day-to-day life in Berlin and Dresden during the Third Reich. Doris Kahane is buried in Berlin, in the same cemetery as Bertolt Brecht, in a grave alongside Herbert Marcuse. “It is the family joke,” Anetta said. “They sit there playing cards, all those old Commies.

“We were the elite, we lived in Pankow, which is where all the Party members lived, the big shots,” said Anetta, who at fifty-six still sports a wild mane of orange red hair. She is the head of the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, a group that keeps track of right-wing violence in the former East Germany (Amadeu Antonio was a young Angolan immigrant murdered by neo-Nazis in 1990). “Being one of the elites you felt a special kind of pressure. Even when I was little I felt it. The Wall had just gone up, not to keep people in, but, as we were told, to keep the fascists from the West out. All the Nazis were over there, in control of the government, doing the bidding of their new American masters. The Wall was put in place to protect us, to enable the growth of the antifascist Nazi frei East German state.

“I wanted to be a good Communist girl. A perfect model of East German youth, especially at Buchenwald. In the GDR, Buchenwald was a sacred place, where the heroes of antifascist resistance rose up against the SS. My idol was Olga Benário, who was a great spy and fighter against the fascists from her teenage years. She traveled to Brazil to try to spread workers’ revolution and smoked cigarettes in a most romantic way. She was betrayed to the Gestapo and gassed in 1942, defiant to the end. To me the heroes at Buchenwald were like Olga. They seemed so impossibly brave and good. This was how I wanted to be, ten years old and totally fearless.

“Instead, when they took us to Buchenwald the very first time and I saw the lampshade, I got so upset. We were supposed to think that even though the fascists were willing to stoop to such a level that they would make lampshades out of people, this did not deter the heroes in the antifascist struggle. They battled on to victory. We were expected to follow in their footsteps. Our resolve to oppose the West was supposed to be stiffened by seeing such a miserable thing as the lampshade. Except I couldn’t stop crying.

“It was awful because I was supposed to be setting an example. We were in the vanguard. And here I was crying because I saw a stupid lampshade. The teacher had to lead me away. It was so embarrassing. I felt as if I’d let everyone down, my classmates, my family, the state, the entire glorious future of the German workers’ Utopia. My weakness had betrayed everything.

“Of course, there was this extra added factor, something I didn’t really consider at the time: being Jewish. I mean, I knew I was Jewish, but as a member of the elite, a good little Communist girl, it wasn’t something that was considered a factor. My mother and father rarely talked about it. Good commies didn’t. Why would they? In the GDR there was really no such thing as being Jewish. Judaism was a religion, not a cultural or ethnic designation, and there being no religion in the GDR meant there were no Jews. When we learned about the camps, Jews were not mentioned. Persecution of Poles, yes, Hungarians, yes. Not Jews. It was a shadow existence. Besides, there were so few Jews left in Berlin. They were all dead.

“But that day they showed us the lampshade— the fake lampshade —I think I remembered who I was, a Jew in Germany. Because none of the other children were crying, not the way I was.”

To make sense of the lampshade inside Herr Röll’s cabinet, my friends in Berlin told me, it was essential to understand Buchenwald’s pivotal position in the “foundation myth” of the late GDR, how in the East German version of events, the camp was not freed by Patton’s army but rather “self-liberated” by the prisoners themselves under the command of the red kapos, the Communist leadership of the inmate underground. It was these men, people like Ernst Busse, the “camp senior number two” in charge of the infirmary; Robert Siewert, head of the construction detachment; and Hans Eiden from the prison clothing department, guided by the inspiration of the murdered Ernst Thälmann, leader of Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD), who drove the fleeing SS from the camp on April 11, 1945, at precisely 3:15 in the afternoon, the time memorialized to this day by the stopped clock on the camp gatehouse. The Americans may have been around but played no part in the liberation.

Читать дальше