That’s when he came into view: an enormous reddish brown man, three hundred pounds if he was an ounce, Beach ball—like shaven head mounted recklessly atop a much bigger but equally round protruding belly gave him the aspect of a dark snowman or a fat, stern Buddha. Attired in nothing but flip-flops and a pair of soaked-through maroon shorts clumped about his genitals, the guy, who looked to be in his mid-thirties, was standing on the opposite side of Claiborne, fleshy arms raised above his head, both middle fingers extending upward in a double fuck-you. If Bush had been looking out the window, waving like Laura, there was no way he could have missed him.

“Okay. Show’s over,” said the NOPD officers as they got in their cruisers and drove off. People began trudging down Claiborne, but the man in the maroon shorts did not move. Rain pelting off his brown skin, he held his stance, middle fingers raised. The way he stood there, his giant stomach hanging over his shorts, accusing fingers pointed to the roiling sky on the anniversary of the disaster, he was like an angry prophet confronting God.

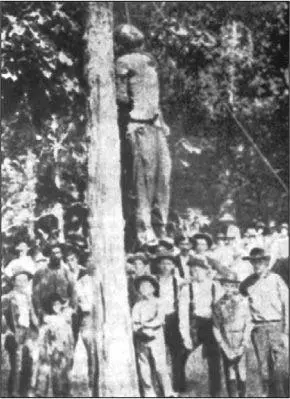

Two lynchings: Masha Bruskina and an anonymous black man

• • •

I was convinced there was a link between the terror of Buchenwald, where the story of the lampshade began, and this sad, beaten-down New Orleans, where the most recent incarnation of the icon had turned up. But I couldn’t quite put it together. There was something missing, some piece that could not be supplied by a professor or scientist. So it was a good thing to run into Mac Rebennack, aka Dr. John the Night Tripper, author of the unbeatable acid voodoo record Gris-Gris and always my favorite New Orleans musician, at least among the white guys.

Just the night before, I’d seen the Doctor playing at Lincoln Center along with Wynton Marsalis, another, albeit far more kempt, New Orleans refugee. Now, the next morning, we were booked on the same flight from LaGuardia to Armstrong Airport. The plane was delayed, and since at the previous night’s gig the Doctor had played “Witchy Red,” a composition about a “conjure woman” who carried “a mojo satchel made of human skin,” this seemed as good a time as any to provide Rebennack with a short version of the lampshade saga.

“That’s a weird story,” said the Doctor, who was attired in a blue silk jacket with an NOPD patch and gold-buckled blue suede shoes. “But there are a lot of weird stories in New Orleans, especially since the storm. Things are off the hook, out of whack. You see all kinds of birds hanging with birds that they never hung with before. They got these giant watermelons growing out in St. Bernard Parish. Botanists from LSU are studying them with stethoscopes. The whole balance of nature is backwards. Every time I fly into the city, I look out the window to see what’s there and what’s not.”

The Doctor was enraged over what had happened during the storm and since. He’d cut a number of songs protesting the wetlands destruction and appeared at benefit concerts to aid the displaced. “All my life I heard people saying they was just trying to live through the Long dynasty,” he said. “Now I’m just hoping my coonass gets through the Bush dynasty.”

I asked the Doctor if, in his long interface with the hyped-up New Orleans voodoo tradition and its attendant sub-rosa spiritual arts, he’d ever heard of anyone who dabbled with human skin, someone who might have knowledge of something like the lampshade.

“Not off the top of my head,” he replied. “But I’ve been out of town.” As far as he knew, outside of Sallie Ann Glassman, the Bywater Jewish voodoo priestess, all the decent practitioners had left town after the storm. But he said he’d think about it. In case anything came to him, I gave him my number, thinking that would be the end of it.

A few weeks later the phone rang sometime after midnight. “This is Mac,” the Doctor said. “Can’t get that lampshade off my mind. It’s haunting me. I got some Jewish on various sides of family, you know. There’s everything else, but there’s Jewish, too. I got this uncle who parachuted behind Nazi lines during D-day, and another uncle who was fighting in the Spanish Civil War against the fascist fuckers. When World War Two started up, he tried to enlist on the German side. My father couldn’t hack that. They had to put that uncle of mine away, on account of his imbalance. War is like that, I suppose. It puts you over the line.

“But whatever it is, I don’t think I can leave this lampshade shit alone. I remembered a guy who messed with that sort of human skin thing. He hung around the Saturn Bar on St. Claude. Can’t recall his name right now, but it’ll come to me. When it does, I’ll call you back.”

Over the next few months I received a scattered series of late-night calls from Rebennack. Sometimes he’d be barely intelligible. Other nights he’d rage eloquently about conditions down in New Orleans.

“I have been radicalized,” the Doctor declared. “You know in New Orleans there’s all kinds of evil. There’s the fake evil, for the tourists. Hoodoo, voodoo, bullshit-doo. That’s the kind of evil that’s fun, the kind when you step out a bit. I’ve done that. I got a whole Ph.D. in the breaking of totally reasonable rules. The silly evil is the stuff you go with to make a little money and to take your mind off the real evil, which is out there in the streets at the end of a rusty knife. The bullet in the head. The body in the river with the arms and legs pulled off. That’s why you make up the fake evil, to keep you from thinking about the real evil. But I can deal with that. What I cannot deal with is the institutional evil. Slavery was an institutional evil. What happened down here with Katrina is like that, the way the wetlands were eaten away, the way the city’s run, the way the private armies moved in, what you had with Bush. A whole way of life being swept away. That’s the institutional evil. Nazi evil. That’s what you got to fight. What you was put on this earth to fight! What you got to go down fighting to fight, if need be.”

Then one night Rebennack called and said the name of the man by the Saturn Bar who messed with human skin had come back to him.

“It’s Cheeky,” he croaked. “Cheeky Felix. Felix. F-E-L-I-X. Like the cat. But it could be Felice. Creole guy. He used to mess with human skin. Made masks of human skin. Slip them right over your head, give yourself a whole new face. He’s probably a bit older than me. So he might be alive. He might not. But that’s his name.”

I put the word out, but no one knew a Cheeky Felix. Trips to the tumbledown Saturn Bar were equally fruitless. Back in the day the Saturn was run by one of the old-time characters, O’Neil Broyard. The first time I had gone by there, the place seemed open, never a sure thing, but the door could not be budged. It turned out that O’Neil was inside, asleep, his head propped up against the front door like a pillow. But now O’Neil was dead, and the Saturn Bar had moved in the video poker machine, so there was no help there.

News that no one seemed to remember Cheeky Felix bugged Dr. John. “Before the storm, you would have found someone,” he said. “Definitely.” The interruption of the chain of oral history was one more tragedy. “No one can remember nothing. It’s like the storm blew the memories right out of their head.”

I got a lead from Andy Antippas, who owns Barrister’s Gallery on St. Claude Avenue only a few blocks from Skip Henderson’s house. Antippas, a sinewy chain-smoker from the Bronx and one-time English literature professor, has one of the best collections of African art in the country. He also runs a gallery where he favors what he calls “the transgressive and biological.” In his front yard he had an eight-foot statue of the Bahamut, an Arabian-influenced manifestation of the devil, constructed wholly from a pile of bones Antippas purchased from a Freemason temple that had fallen on hard times. It was this sort of “unusual” taste, Antippas allowed, that almost got him locked up in the Dave Dominici cemetery case.

Читать дальше