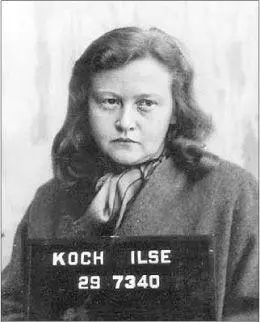

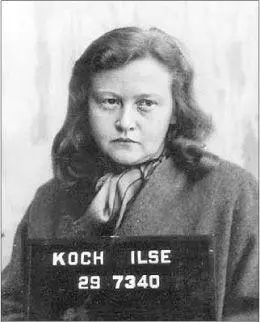

By 1947, at her trial before the war crimes tribunal at the former Dachau camp, Ilse Koch no longer resembled the ingénue who married Karl Koch just a decade before. She looked haggard and worn, in part due to the fact that despite being incarcerated for months, Koch was, shockingly, pregnant, father unknown. Some months later, when she gave birth to a son, the child was not greeted into the SS clan as one more potential Norse god on earth. Listing the event in its Milestones section, Time magazine noted, “Born, to Ilse Koch… a male bastard.”

The trial of Ilse Koch was a worldwide sensation. She was, after all, the perfect defendant, perfectly pregnant, perfectly sourpussed, bearing the perfect nickname, “the Bitch of Buchenwald,” a cannily alliterative mistranslation of her prison epithet, die Hexe —“Witch”— von Buchenwald . She was the “Lady of the Lampshades,” whose crimes—the blithe defilement of the human body—struck many as even more indicative of Nazi evil than the killing of millions. The fact that she was a woman, a red-haired black widow, made it all the more shocking.

The testimony was properly lurid. “I had several occasions to see Ilse Koch and also to have personal business with her,” testified Kurt Froboess, a prisoner at Buchenwald from its opening in 1937 until liberation, describing an incident in which he and a Czech chaplain were digging a ditch to lay cables. The chaplain tossed some dirt out of the hole, Froboess said. “Suddenly someone was standing on top of the ditch and was yelling, ‘Prisoner, what are you doing down there?’ Someone was standing with her legs straddling the ditch. We looked up to see who it was and recognized Mrs. Koch. She was standing on top of the ditch without any underwear and a short skirt. As we did this, she said, ‘What are you doing looking up here?’ and with her riding crop she beat us, particularly my comrade.”

Describing another encounter, Froboess testified, “It was a hot day. Some of them [the prisoners] were working without a shirt. Mrs. Koch arrived on a horse. There was a comrade there—his first name was Jean, he was either French or Belgian—and he was known throughout camp for his excellent tattoos from head to toe. I particularly recall a colored cobra on his left arm, winding all the way up to the top. On his chest he had an exceptionally well-tattooed sailboat with four masts. Even today I can see it before my eyes very clearly. Mrs. Koch rode over until she came pretty close and had a look at him. And she told him, ‘Let’s work faster, faster.’ She took his number down. Jean was called to the gate at evening formation. We didn’t see him anymore.”

About a half year later, Froboess continued, he had occasion to visit a friend of his who was working at the Buchenwald pathology department, and there he saw “the skin and to my horror I noticed the same sailboat that I had seen on Jean.”

On August 14, 1947, Ilse Koch, guilty of participating in a “common plan” to violate “the Laws and Usages of War” during her tenure as Kommandeuse of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, stood before the court in a frumpy checkered dress and was sentenced to life in prison. Despite all the testimony about human skin lampshades and bookbindings, no such object was introduced in evidence. For her part, Ilse Koch steadfastly denied ever owning a human skin lampshade or ordering one made. She claimed the first time she ever heard of any lampshades was when “I read about it in Life magazine.”

TWO

But we are getting ahead of ourselves, if not in time, in terms of telling this story. To get to the beginning we have to back up some seventeen years from today, to a beastly hot summer day in Clarksdale, Mississippi, a ramshackle town of about twenty thousand in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, which isn’t a river delta at all but rather a diamond-shaped expanse of topsoil-rich land once home to the American South’s largest cotton plantations. [3] Clarksdale, known as “The Golden Buckle of the Cotton Belt,” was the key commercial center of the Mississippi Delta, the most fertile (along with the Nile Valley) cotton growing area in the world. The concentration of cotton plantations and the later sharecropping system in the Delta did much to create the dynamic that produced African-American blues music. For an excellent overview of the social and economic conditions of the Delta at the time, see Nicholas Lemann’s The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America (Vintage, 1992). Muddy Waters’s sharecropper shack once stood on the Stovall Plantation near Clarksdale until it was purchased and hauled away by the House of Blues on a flatbed truck. Many sign-waving local music fans chased after the truck screaming, “Don’t take Muddy’s house away.”

It might not look it at first glance—the landscape flat as a board, and the magnolia trees growing wild in unkempt backyards—but Clarksdale has a lot in common with the Thuringian hills of Weimar, home to both the most brilliant flowering of German humanism and abject Nazi barbarism.

This assertion stems, in part, from Clarksdale’s indisputable position as the epicenter of early African-American blues music, a shriek of syncretic pain born during the dislocation of slavery that eventually morphed into rock and roll, which along with Hollywood came to dominate the cultural life of the twentieth century much as Weimar held sway over the eighteenth and nineteenth. Charley Patton, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Son House, Howlin’ Wolf, and many other artists spent large parts of their lives in Clarksdale. Sam Cooke was born here. After a car crash one night on a lonely stretch of blacktop, Bessie Smith died in the makeshift emergency room of the Clarksdale colored people’s hospital, which later became the Riverside Hotel, where Ike Turner lived as a boy.

More specific to this story, however, is Clarksdale’s close proximity to the intersection of U.S. highways 49 and 61. This is the famous “crossroads” where, legend has it, bluesmen came to sell their soul to the devil in exchange for becoming the best guitar player and singer anyone had ever heard.

This is the often-quoted testimony of Tommy Johnson, who, like Robert Johnson, author of the iconic song “Cross Road Blues,” claimed to have undergone the process. “If you want to learn how to make songs yourself,” Johnson said, “you take your guitar and you go to where the road crosses that way, where a crossroads is. Be sure to get there just a little before twelve that night so you know you’ll be there. You have your guitar and be playing a piece there by yourself… Then a big black man will walk up there and take your guitar and he’ll tune it. And then he’ll play a piece and hand it back to you. That’s the way I learned to play anything I want.”

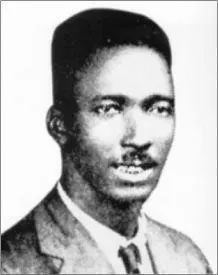

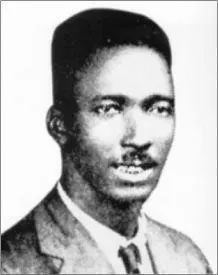

Tommy Johnson, Delta bluesman

It is a narrative that Goethe would have recognized, sitting under his oak tree, the poet’s bemused Mephistopheles being archetypical kin not only to Tommy Johnson’s “big black man” but also the Celtic Puck, the Norse Loki, the Hopi Kokopelli, and a dozen more supernatural trickster/soul barterers. For the Clarksdale bluesmen, the story almost certainly accompanied their forebearers on the slave ships. Called Eshu by the Yorubans, Anansi among the Ashantis, Legba throughout the Caribbean, the god of the crossroads appears in many African mythologies. He waits at the spot where pathways come together, that existential point where options become palpable. Often depicted leaning against a rock, sometimes chewing on a long reed, the crossroads god asks the arriving traveler what direction he’s going, if perhaps he needs a little help finding his way. Not that his advice can be trusted: the riches he claims are down the road come with an even greater toll. But the human sojourner—be he Faust or Peetie Wheatstraw, another bluesman who supposedly went to the intersection of highways 61 and 49 at midnight—is no fool; he knows who he’s up against. That’s the trick of it, an inbred human trait, a cocky hubris of sorts, trying to beat the devil at his own game, if you can.

Читать дальше