From the start, Koch imposed a reign of relentless cruelty at the camp, marked by innovative tortures, including the infamous “tree hanging,” in which prisoners were strapped to a ten-foot-tall pole with their hands tied behind their necks, sometimes for days. Another practice was a particularly noxious form of waterboarding in which victims were pushed facedown into the vile open latrines. The Koches’ domestic extravagance was an obscene counterpoint to these horrors. At the grand Villa Koch, where dozens of prisoners were employed as plantation-style domestics, dinner was served on the best china and eaten with the finest silver. It would later be proved that the ex-banker Koch and his cronies financed much of this opulence by embezzling camp money and stealing from terrorized inmates.

No small amount of this loot went toward keeping up with Ilse Koch’s ever expanding needs and desires. The former Dresden working-class girl took to the highlife of a concentration camp overseer. Anxious to keep his wife happy, Koch showered her with gifts—from fine clothes to inlaid wood furniture to diamond rings—mostly made by or stolen from prisoners. If Frau Koch desired to take a bath in Madeira, as she reportedly did, the wine was provided. In 1939, thinking his wife might like to learn to ride a horse, Koch commissioned the construction of a thirty-thousand-square-foot private riding hall with mirrored walls and a sixty-foot vaulted ceiling outfitted with dramatic skylights. According to the Buchenwald Report, compiled shortly after the war by the U.S. Army and former prisoners, as many as thirty prisoners died in the rush to finish the hall, which cost in excess of 250,000 marks. When the Kommandeuse, as Ilse Koch was called, took morning canters around the ring, the Buchenwald prisoners’ band provided musical accompaniment.

For many, this would be the enduring image of Ilse Koch: provocatively seated atop her favorite steed (usually remembered as milky white), riding crop at the ready, black leather boots to her knee, and all that red hair. Later, after the war, there would be much talk of the scantily dressed Kommandeuse, riding through the camp, stopping only to accuse men of lasciviously staring at her breasts and her bottom, a crime for which the punishment was a beating or death.

It must have seemed an incredible dream to the Kommandant’s wife, a prize not unlike that granted by the forces of darkness in a dozen retellings of the Faust myth. Saved from drudgery by becoming a Nazi, she was soon accompanying her frog prince husband to Himmler’s Wewelsburg castle with its eighteen soaring towers. Declared by the Reichsführer as “das Zentrum der neuen Welt,” or “the center of the new world,” Wewelsburg was a place where Ilse, as a member of this all-powerful new Chosen People, would always be welcome.

It was sometime in the summer of 1938, according to Harry Stein, the chief historian at the present-day memorial at Buchenwald, that Ilse Koch gave her husband a special gift. Many of the SS wives had become fascinated with the work of the SS camp doctor, Erich Wagner, a former student of “race science” at the then Nazi-run Friedrich Schiller University in nearby Jena. Wagner, apparently a dashing sort, was in the middle of compiling his Ph.D. thesis, “Ein Beitrag zur Tätowierungsfrage,” or “A Contribution on the Tattooing Question,” a report on the relationship between tattooing and criminal behavior. In the process of his research, Wagner and other doctors in the camp pathology block reportedly began to remove the skin of prisoners with particularly colorful and/or lewd tattoos. Inmates would later say that many of these dried and tanned tattooed skins were stitched together into gloves, bookcovers, and lampshades. It was one of these lampshades, Harry Stein said, that was given by Ilse Koch to Karl Koch as a present for his birthday. [2] Buchenwald doctor Erich Wagner, whose thesis on tattooing was supposedly read by Ilse Koch (the thesis itself appears on the Buchenwald Table, at the base of the lampshade), was brought to the United States as a prisoner of war. Escaping custody, Wagner returned to Europe, where he practiced medicine under an assumed name until he was recaptured. He committed suicide in prison in March 1959. Wagner’s work in the identification of “criminal types” seems to lean heavily on the ideas of Cesare Lombroso, the nineteenth-century Italian psychiatrist and surgeon who is generally considered to be the father of modern criminology. Born into a well-to-do Sephardic family in Verona, Lombroso believed that “born criminals” could be recognized through eugenic-based characteristics of “biological determinism” such as handle-shaped ears, hawklike noses, and insensitivity to pain. It was Lombroso’s belief that individuals displaying these signs of “atavistic stigmata” were more likely to have tattoos. Studies of the connection between tattooing and criminal activity of groups like the yakuza, Russian crime societies, and Latin American gangs are now standard police work. While gang tats can be quite elaborate, the old-style jailhouse tattoo remains an entire genre of self-branding. Most prison tats are quite primitive, owing to the meager resources at hand, with colors restricted to blue or black. Most are still done “freehand,” by a needle dipped in ink, but homemade tat machines, usually powered by a small motor and a 9-volt battery, are also common. For a wide array of what’s available to the long-term jailbird, check http://www.eviltattoo.com/pr .

“It was considered the most favorite of all the presents given to Karl Koch,” Harry Stein said. “All the guests applauded.” It seemed, at the time, a token of love between husband and wife.

The first published account of the Ilse Koch “Lady of the Lampshades” story appeared in the U.S. Army publication Stars and Stripes on April 20, 1945, Adolf Hitler’s fifty-sixth birthday, nine days after the liberation of Buchenwald. Ann Stringer, a UPI correspondent, filed a story from the camp saying she had seen a lampshade, “two feet in diameter, about eighteen inches high and made of five panels… made from the skin from a man’s chest. Along side were book bindings, bookmarkers, and other ornamental pieces—all made from human skin, too. I saw them today. I could see the pores and the tiny unquestionably human skin lines.”

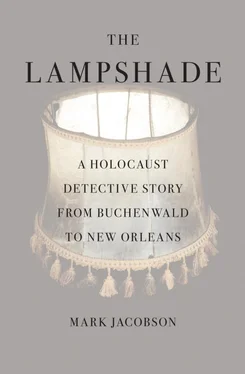

Young Ilse Koch

This was the first time people outside the Buchenwald camp had heard of Ilse Koch and her alleged passion for objects made from human skin. One prisoner, identified in Stringer’s story as “a Dutch engineer,” described how the former Kommandeuse “would have prisoners with tattoos on them line up shirtless. Then she would pick a pretty design or mark she particularly liked. That prisoner would be executed and his skin made into an ornament.”

By the end of 1941, the Nazi dream-life of the former Ilse Köhler began to collapse around her. Karl Koch was transferred from Buchenwald to Lublin, Poland, to oversee the construction of Majdanek camp, where eighty thousand people would die, most of them Jews and Soviet prisoners of war. In 1943, Koch, his largesse with Himmler used up, was convicted by an SS court of corruption and murder charges. He was returned to Buchenwald in chains and executed by a firing squad on April 5, 1945, only a week before the American troops arrived at the camp. By then, Ilse, her fabulous riding hall now a shabby warehouse, had fled to the small town of Ludwigsburg, where she was recognized by a former Buchenwald prisoner and turned over to the Allied authorities.

Читать дальше