“To me, that is one of the great ironies of it, an irony I understood very well at Buchenwald. SHAEF was very smart to give me the job of tour guide that day. They couldn’t have gotten anyone better. Those people claimed to be innocent, but I knew they weren’t. I knew that because I knew them. They said they were crying because they didn’t know. But that was a lie. They were crying because they did know. They were hoping their tears would absolve them, as if someone would pat them on the head and say, don’t worry, it’s going to be all right. But they had the wrong guy for that. The trains ran to Buchenwald every day. People from Weimar worked at the Gustloff factory next to the camp. Guards lived in the town. So don’t say you didn’t know, because you did. You knew .” [18] On January 27, 2003, Jorge Semprún addressed the German Bundestag as the keynote speaker of a Day of Remembrance for the Victims of National Socialism, and once again called up his memories of Albert G. Rosenberg. Retired from his post as the Spanish minister of culture, Semprún recalled his days at Buchenwald, saying that even if it was his “good fortune to meet many individuals of exceptional humanity, intellectual acumen, possessed both of anger and moral courage,” it was Rosenberg that he remembered most. He spoke of their talks about philosophy, their drive across “the landscape of Goethe, on the Ettersberg,” and recollected the quiet authority Rosenberg displayed while speaking to the Germans from Weimar, telling them not to say they were innocent when they were not. Semprún explained he’d changed Rosenberg’s name to Rosenfeld in his book Literature or Life because he did not know if the American was dead or alive, and to avoid the possibility that Rosenberg would feel “disturbed or injured” by his depiction. Mentioning that Rosenberg himself had lost twenty-eight family members in the Holocaust, Semprún said he knew the story of the American soldier was far from over. Perhaps someday, the then seventy-nine-year-old Semprún said, he would write about Albert Rosenberg again. When I saw Rosenberg in El Paso in 2008, five years after Semprún’s Bundestag speech, I asked him if he’d ever heard from the writer. No, Rosenberg said. But that was fine.

Eating taco chips, we sat at Rosenberg’s dining room table looking over some of his “souvenirs.” He had “stacks of stuff” from the war, which he kept in the “magic closet” where he once stored the remaining copy of The Buchenwald Report .

He had his “SHAEF pass,” which he referred to as “the ultimate Eisenhower get-out-of-jail ticket, a 007 James Bond license to kill that let us do basically whatever the hell we wanted.” Dated 18 February 1945, the pass said in bold capital letters, “THE BEARER OF THIS CARD WILL NOT BE INTERFERED WITH IN THE PERFORMANCE OF HIS DUTY BY THE MILITARY POLICE OR ANY OTHER MILITARY ORGANIZATION BY COMMAND OF GENERAL EISENHOWER.”

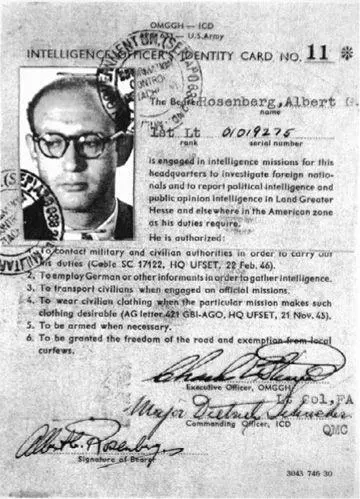

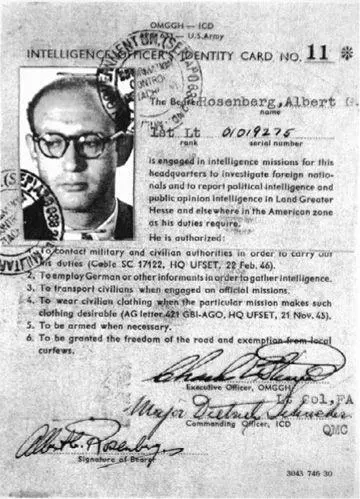

He had his “intelligence officer’s identity card” with a picture of him as a young man with horn-rimmed glasses and a far-off gaze that made him seem more like a young Arthur Miller than a spy or a soldier. He had copies of old Nazi newspapers, photographs from the camps, and a translated letter dated November 29, 1941, sent from Gestapo chief Reinhard Heydrich to SS Gruppenführer Otto Hofmann of the Reich Race and Settlement Main Office inviting him to a meeting at Wannsee “in regard to organizational, practical, and material measures requisite for the total solution of the Jewish question in Europe.”

He had a prayer book given to him by a relative. “It was the prayer book of my favorite uncle,” Rosenberg said. “He kept a diary day to day, separated by years, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943. Then nothing. Nothing.”

It was quite a collection, but not all that it once was, Rosenberg said matter-of-factly. For years he had a piece of tattooed human skin that he had taken from the Buchenwald Table, just as Major Schmuhl, whom Rosenberg remembered as a “heavy-set sort of man,” had taken the lampshade.

“It was a tattoo of a woman, with a hat on her head. It came from a man’s chest because you could see the nipple alongside the girl’s head.”

Asked why he took the piece of skin, Rosenberg shook his head. “I have asked myself that same thing many times. In the beginning it seemed like no big deal. At the time there seemed to be many such objects at the camp. The pathology block was a veritable factory of human skin products. Ilse Koch was supposed to have had gloves of human skin, purses of human skin, a whole Paris collection. There was no reason not to believe any of these stories. You heard them over and over again. Everyone said pretty much the same thing… We had entered hell, so there was no surprise to see hellish things. To me the skin was just one more incredible item. It was years before I came to the conscious realization that that curled-up little piece of tanning had once been part of some poor soul’s hide.

“Then I couldn’t stand to have the thing near me anymore. I was having so many terrible dreams—I still do—and the tattoo had so many associations. The Nazis had perpetrated the worst crimes in the history of the world and here I had this little knickknack. God!

“I asked myself, why do I keep this awful thing? I was ashamed to have had it for so long. But I couldn’t quite part with it. It was some kind of pathology perhaps. I went to psychotherapy for years and still couldn’t figure it out. It was like it was part of me. I locked it up in a safe-deposit box at the bank, but it still haunted me. I sent it to a friend in Chicago. I told him to give it to Yad Vashem, do whatever you want. I never found out what finally happened with it and don’t want to know.”

Rosenberg sat there for a moment, looking out the window. It was midafternoon now and the winter sun was sinking behind the jagged peaks visible over the fence behind his apartment.

“What did you say that fellow called his movie? The one who thinks I brought the shrunken heads from Brazil? Buchenwald, Stupid Evil ?”

“No. Dumb. Buchenwald: A Dumb Dumb Portrayal of Evil. ”

“Dumb Dumb.” Rosenberg smiled wearily. “Well, that’s not a halfbad title, when you think about it. Evil is dumb. That is why it is evil. There are so many stupid people in the world willing to believe stupid things; put them all together and they can be very, very stupid. A stupid, dangerous crowd out for blood. To me, that’s what the Nazis were, one gigantic lynch mob.”

As for Denier Bud’s assertion that the PWD set up the Buchenwald Table, Rosenberg could only roll his eyes. The idea that Psychological Warfare did political propaganda was no great insight. “We were in the political propaganda business, for chrissakes,” Rosenberg said, with a cagey smile that seemed to indicate that once an intelligence man, always an intelligence man. Rosenberg supposed he could have “gone into the spy business.” The PWD was an easy, entry-level step to the OSS and the CIA beyond. One of the young men in his unit, called “Kampfgruppe Rosenberg,” was Michael Josselson, then an international buyer for Gimbels but soon to be the head of the CIA-run Congress for Cultural Freedom that would fight the intellectual Cold War in Europe. Among Josselson’s many projects was Encounter magazine, which was edited by Stephen Spender and Irving Kristol and published the work of such people as Arthur Koestler, James T. Farrell, Ignazio Silone, Bertrand Russell, and Sidney Hook. These career pathways were open, Rosenberg said, for the right sort of person.

Читать дальше