Semprún writes that it was in one of these conversations that Rosenfeld first told him that Martin Heidegger had been a National Socialist as far back as 1933. Rosenfeld revealed that the philosopher hadn’t lifted a finger to help when his revered teacher, Edmund Husserl, was barred from the university for being a Jew. As a schoolboy, Semprún had spent “long, austere” winter evenings oppressed by Heidegger’s dense prose, hacking his way through “torturing pseudo-etymologies,” “purely rhetorical resonance,” and “assonance.” Completing his assignments, the young Semprún had wondered: did these ideas mean anything in any language other than German? It was almost a relief to hear that Heidegger was a Nazi; in retrospect, this was the only part of the man’s work that made any sense.

Although he never quite comes out and says it, Semprún’s chapter on Lieutenant Rosenfeld is an extended thank-you note. In the measured way the American liberator dismisses the self-serving obliviousness of the people from Weimar, in his manhandling of the old Hitler supporter at Goethe’s house, and most of all in his open-handed intellectuality, it is Rosenfeld who pulls Semprún from what he calls “the whirlwind of nothingness, the nebulous void.”

In Literature or Life, Semprún says it is only when he sees Allied soldiers gazing at him with a kind of morbid curiosity that he begins to realize he is indeed alive and again responsible for all that breathing and thinking entails. Until then he was somewhere in between, which, he says, puts the lie to the statement by Ludwig Wittgenstein (whom Semprún calls “this idiot”) that “death is not an event of life. Death cannot be lived.” To be in the camp was to be in both, to “cross through death,” like the forty-nine-day bardo described in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Returning to life is no simple journey, Semprún says. “Many people who will come out of this place will not be survivors, they’ll be ghosts, revenants.” It is Lieutenant Rosenfeld, this German Jew returned “to fight against his own country,” this tough-guy spouter of poetry and philosophy who has arrived, like Charon rowing against the current, to deposit Semprún back on the shore of the living.

The two men spend a lot of time discussing Rosenfeld’s Buchenwald project. To tell the story of the camp, and do it in three weeks, is an impossible assignment, Semprún says. How to speak of these things in a way that both satisfies the moral parameters of the situation and translates it into the crabbed language demanded by SHAEF? Where should the story start? With Goethe? With the birds driven away by the smoke? It is difficult to know, says Semprún, who will spend much of his life looking for a way to tell his own version of the story.

One thing is certain, however, Semprún tells Rosenfeld: the simple chronology, the facts and figures, are insufficient. You could recount the story of “any day at all, from reveille at four-thirty… the fatiguing labor, the constant hunger, the chronic lack of sleep, the persecution by the Kapos, the latrine duty, the floggings from the SS, the assembly-line work in munitions factories, the crematory smoke, the public executions… the death of friends,” and never compile a true history of Buchenwald.

“What’s essential,” Semprún says, “is the experience of Evil… You don’t need concentration camps to know Evil. But here, this experience will turn out to have been crucial, and massive, invading everywhere, devouring everything… It’s the experience of radical Evil.”

Hearing this, Lieutenant Rosenfeld looks at his young compatriot “sharply.” “Das radikal Böse,” he says.

Semprún looks back at Rosenfeld, in amazement. So this man who has pulled him back to the living knows Kant as well?

“Of course,” Rosenfeld says.

Albert Rosenberg in El Paso

“Das radikal Böse…,” murmured Albert G. Rosenberg, as he sat in the living room of his apartment in El Paso, repeating the famous phrase from Immanuel Kant’s 1793 treatise Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone . It was sixty-three years since he had discussed these matters with Jorge Semprún inside an SS office at Buchenwald. Now Rosenberg lived a few miles from the Mexican border with his wife of thirty years, Lourdes, in a modest two-bedroom apartment in a hillside subdivision.

He said, “ Radical evil was Kant’s term to explain what happens when evil, which he believed was an inherent human trait, is unchallenged by the exercise of free will. Free will, coupled with certain maxims of the good, keeps evil at bay. It is on the state level, such as in the totalitarian, dictatorial society in which the free will of the people is completely oppressed, that evil becomes dominant. It becomes the way of things— das radikal Böse .”

Then, his blue eyes suddenly infused with a mischievous glint, Rosenberg laughed. As sharp as ever, he was nonetheless tickled that he still remembered something about Kant, whom he hadn’t thought about “for decades.” But there was the German educational system for you. Even with the Nazis coming to power, the gymnasium wasn’t the paltry sort of thing that passes for learning in the United States. Drummed into the brain, a German education had staying power.

Who knew how Kant might have chosen to define the word radikal had he been writing in 1945 rather than 1793, but the Prussian philosopher had “come pretty close” to predicting the way the Third Reich worked, Rosenberg thought. This didn’t make Kant clairvoyant, he said. Rather it was that “the dark side of German character was there a long, long time before Hitler came on the scene.”

“Radical evil—total destruction of opposing will, wiping it out, sending it up the smokestack—that was what the camps were,” said Rosenberg, who said he never felt sadder than the day he took his SHAEF jeep and drove to Bergen-Belsen, the camp in Saxony where he’d heard that several of his relatives had been sent by the Nazis.

“I drove through the camp, through that horrible death, people lying there staring into space, shouting on my U.S. Army bullhorn, screaming out to see if anyone knew the Rosenberg family from Göttingen. I found no one. Later I met one of my relatives, my cousin Henry, one of the few who survived—twenty-eight died—and he told me he heard me. He heard me shouting! But he could barely move. He couldn’t answer my call.”

Literature or Life took him by surprise, Rosenberg said. He vaguely remembered Jorge Semprún, the twenty-one-year-old partisan and philosophy student, and had no idea that Semprún, whom he had not seen or spoken to since those days in the Ettersberg woods, would remember him so vividly.

“When I first picked up the book and saw that chapter ‘Lieutenant Rosenfeld’ and began reading it, I thought, who could have dreamed this? Who could have imagined my life like this? But it wasn’t a dream. It happened. To me, and him.” That said, even though he thinks Literature or Life is “a masterpiece,” there are things in it that he did not recall happening quite the way Jorge Semprún did.

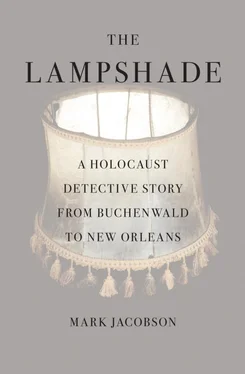

Semprún described the tone of his speech to the people from Weimar as “neutral” and that was good, Rosenberg said. “But I didn’t feel neutral. I was seething. Göttingen, where I grew up, was not all that different than Weimar. A shitty, right-wing town. Full of fascists. They tried to kill me in Göttingen, but it could have just as easily been Weimar. For all the lovely history and poetry, it was that kind of place. Those people from Weimar—I took them around, showed them the crematorium, the places where the medical experiments took place, where the Nazis ripped off the prisoners’ skin and made the lampshades… I might have sounded neutral, because that is the way a soldier is supposed to conduct himself. My father was a soldier. He fought for Germany in the First World War. Fought for these same people! The same people who fifteen years later would follow Hitler!

Читать дальше