“Making lampshades out of human skin is another manifestation of evil,” Berenbaum said. This didn’t, however, mean that the lampshades had to seen, much in the way that one didn’t need to put a corpse on public display because a murder has occurred. To show the artifacts of human skin in the way that Kipperman was advocating, Berenbaum said, was to run “the risk of almost being pornographic.”

Nearly ten years later, the sound of the word still incensed Kipperman. “ Pornographic! That’s what they think. Does that mean it shouldn’t be seen, that it should remain hidden? These officials, these big-shot know-it-alls, they think they can decide what can be shown and what cannot.

“That is wrong. I don’t care what anyone says. The Holocaust cannot be censored.”

A few months after first talking with Kipperman, I visited Berenbaum at his home in the Fairfax district of Los Angeles. No longer involved in what he called “the office politics” of the USHMM, he was now the director of the Sigi Ziering Institute, a board member of the Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance, and a rabbi at a Long Beach congregation. Of course he remembered Ken Kipperman, the man who tried to blow up the Holocaust museum even before it was built, Berenbaum said, with a shake of his head.

It wasn’t as if he doubted Kipperman’s passion or his sincerity, Berenbaum said, sitting in his tasteful living room. He could understand the impulse to show everything, to hold nothing back. But it wasn’t that simple. The matter of human remains, Berenbaum said, was “a very problematic, a highly emotional area.” It required a larger understanding of the factors at work. From the religious point of view, Berenbaum, ordained as an Orthodox rabbi when he was twenty-three, said there could be very little debate. All human remains of Jewish origin must be buried. Mosaic law was quite clear on that. It was in the social and political realm that “heated discussion” often arose.

“There was the issue of the hair,” Berenbaum recalled, citing perhaps the most difficult of “representational” disputes at the USHMM: whether or not to exhibit the hair shorn from the heads of the camp victims and later used by the Nazis, in their utilitarian way, to stuff pillows and spin into yarn. Noting that two tons of hair is displayed at the Auschwitz museum, some of the USHMM planners felt that a similar exhibit would be an effective way of telling that part of the story. Others objected, pointing out that since Auschwitz was the scene of the crime, showing it there carried the weight of evidence. In America, however, in a museum geared for an American audience, such a display might seem gratuitous, “an exhibit out of place.”

An early vote among the planners in favor of exhibiting the hair was overturned following a plea by a number of survivors who felt it would be disrespectful to the victims. “In the end this was what mattered most, the wishes of the survivors, whom it was felt had the weight of moral authority on their side,” Berenbaum said. “No one wanted someone to come into the museum and think they might be looking at their mother’s hair.”

I told Berenbaum about my conversation with Diane Saltzman concerning the Katrina lampshade and asked him what he would do if he were still at the museum.

“I don’t know if, in the presence of a DNA report, I would have said it was a myth. But I agree with Diane Saltzman, these types of objects are a distraction. They are a form of pornography because people focus on them to the exclusion of everything else.”

“But if they exist, you can’t ignore them, can you? What should be done about them?”

Berenbaum exhaled. It was Father’s Day. He was looking forward to dinner with his family. This wasn’t a conversation he wanted to have, not now, probably not ever.

Pressing the issue, I asked Berenbaum about a story I’d heard from E. Randol Schoenberg, the grandson of the composer Arnold Schoenberg. Randol’s wife had coincidentally been a college friend of Skip Henderson’s wife, Fontaine. A well-known Los Angeles attorney, Schoenberg successfully pursued the case in which five Gustav Klimt paintings stolen by the Nazis that ended up in the hands of the Austrian government were returned to their original owners. Schoenberg told me he’d heard that Berenbaum had once purchased an object purported to be a human skin lampshade off “the black market” and had it destroyed “just so the thing wasn’t out there anymore.”

Asked if this was true, and if he’d bothered to test the lampshade before disposing of it, Berenbaum was noncommittal, saying only that “a lot of junk turns up on these right-wing websites.”

Berenbaum peered across the coffee table and said, “Maybe this will help you. Maybe not. But when we were first making the museum, we acquired a number of canisters that had contained Zyklon B,” he said, referring to the cyanide-based pesticide with which the SS gassed people in the camps.

“At the time I thought this would be no big deal, that it was just another distressing exhibit. But there was a problem. Someone thought the canisters were still dangerous; they called the EPA, who got all excited. These things were fifty-odd years old at the time, they’d been open, exposed to the air. They were harmless. But try convincing anyone of that. It was just the name… Zyklon B… the idea that the label was the same, that was enough. It was the symbol.

“No one wanted to be near these things. I was in charge, so I got stuck with them. They were delivered to me. I put them in my garage until we could have them tested to prove they weren’t dangerous. And let me tell you… that night, the whole time those things were in my garage, that was a very long night. It was enough to send someone to psychotherapy.”

Berenbaum looked at me. “How long have you had this lampshade?”

“Several months.”

“Several months… and it is in your house?” Berenbaum rubbed his forehead.

“Here’s some advice. You can take it or not. What I’ve found is that being around these kinds of things, thinking about them, can drive people out of their minds. I’d get as far away from it as I could.” This was what he was trying to tell Ken Kipperman, Berenbaum said, and this was what he was telling me.

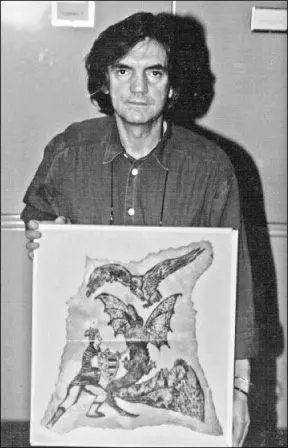

Ken Kipperman with Buchenwald tattooed skin

When I visited him in Maryland, Ken Kipperman was entering the second decade of his quest to call attention to the presence of the human skin artifacts at the National Archives and the National Museum of Health and Medicine. In the beginning Kipperman felt his campaign, which consisted of sending identical handwritten letters to newspapers, TV stations, well-known historians, and public figures asking for “respectful treatment for these victims” was having some success. In 2001 an article about him appeared in the Washington Post Style section. This led to a German documentary called Shadows of Silence, in which Kipperman comes off as an earnest if slightly touched Kafka character, attempting to do the right thing in an impossible situation. But the movie received little distribution, making it one more spectral, hard-to-find artifact. By the time I first spoke with him in 2007, Kipperman had all but abandoned his campaign, although not by choice. He had promised his wife he’d stop.

“That’s why I didn’t want you to come down here, so he’d get encouragement,” Paula Kipperman told me in her lingering eastern European accent, as she prepared a deliciously copious lunch in the family kitchen. “I don’t want him to start all this up again, because I can’t take it anymore.

Читать дальше