Finding no one at the museum to provide him with the answers he sought, he turned his attention to the National Archives, where he met Robert Wolfe. A longtime archivist, Wolfe had only a moderate interest in Kipperman’s tattooing inquiry, but he did, almost as an afterthought, mention that the Archives had a number of pieces of tattooed human skin in its collection.

“He said they had the skin and a piece of a lampshade. From Buchenwald,” Kipperman reports. Wolfe believed the objects had come to the Archives following their use as exhibits during the Nuremberg trials.

“I was completely floored,” said Kipperman, who asked to be allowed to see the objects. This permission was long in coming. “I kept calling and writing, asking for an appointment. They kept putting me off. Everyone was always on vacation.” In the meantime Kipperman, his monomania fully engaged, began spending every nonworking hour in the library at the Holocaust museum and in the vast National Archives, compulsively xeroxing and re-xeroxing any and all material pertaining to World War II—era tattooed human skin. Eventually the Archives allowed him to see their holdings, which, contrary to what Robert Wolfe said, consisted of only one piece of tattooed skin, an image of a woman with butterfly wings. Kipperman took a picture of himself holding the mounted tattoo.

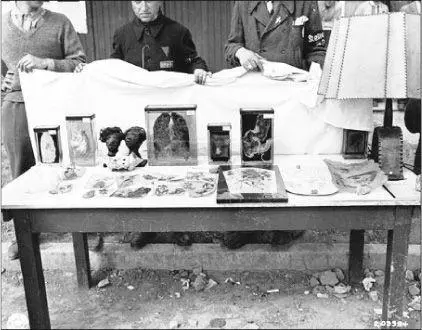

Later he traced more artifacts to the Archives’ annex in College Park, Maryland. There he saw three more pieces of tattooed skin and a bisected shrunken head, all labeled as coming from the Buchenwald camp. On one of those long days at the Archives he came upon an oddly familiar picture.

“It was the Table. The Buchenwald Table. As soon as I saw it, I knew that this was the same thing I saw on TV back in my parents’ house in Coney Island. The same picture that had been in my head all these years. The shrunken heads, the lampshade—all of it. After forty years, it came back to me, like a ghost.”

The Buchenwald Table, April 16, 1945

From Kipperman’s point of view, the truly horrible thing was that many of the objects on the Buchenwald Table had been in the United States all along, an hour’s drive from his house. “I couldn’t believe it, these awful, terrible things gathering dust right there in Washington D.C., no more than a few hundred feet from the Constitution, the greatest document of American freedom. It made me so upset, I couldn’t think.”

Soon after, Kipperman began his search for the lampshade. “I knew it was missing, that it had disappeared from the Table and had never been introduced in evidence at the war trials. But it had to be somewhere.”

Kipperman found a clipping from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch headlined “Ex-Officer Has Human Skin from Ilse Koch’s Home.” The officer in question, the article said, was Major Lorenz C. Schmuhl, former commanding officer of post-liberation Buchenwald, who had taken home a number of “souvenirs” from the camp, including “most pieces of the famous lampshade.”

Kipperman tried to make contact with Schmuhl, who was placed in charge of the camp on April 16, 1945, the same day the Table was set up to greet the people from Weimar. A World War I combat veteran, Schmuhl was a good choice to run a former concentration camp. He spoke German and had long been the deputy warden of the Michigan City, Indiana, penitentiary. Apparently he ran a tight ship. When John Dillinger, Schmuhl’s most illustrious inmate, was incarcerated at Michigan City, the erstwhile public enemy number one was quoted as saying, “When I get out of here, I’ll be the meanest bastard the world has ever seen.”

“I knew Major Schmuhl had the lampshade from the Table, but had ‘to prove it,’” Kipperman said as he pulled out a murky photo of Schmuhl’s Buchenwald collection that had been published in a 1949 edition of the Indianapolis Star . “The picture’s not too great, but what you see is that a piece was missing from the top of the lampshade in Schmuhl’s house. In the footage from Buchenwald, the lampshade on the table was missing the same piece.” [14] Some of the items on the Buchenwald Table were tested to determine their validity, others were not. Three “tattooed skin hides” were sent to the Army Section of Pathology in New York. A report dated May 25, 1945, signed by Major Reuben Cares, describes “Piece A” as measuring “13X13 cm., is transparent and shows a woman’s head in the center and a sailor with an anchor near the margin.” “Piece B,” a similar size, “is a tattoo of several anchors resting on an indefinite black mass. To the right of this mass is a man’s head.” “Piece C” is “truncated,” with the upper portion showing “two nipples” sixteen centimeters apart. A “black dragon, with fire coming from the mouth, measures 28 cm.” To the left of the dragon “is a man in a coat of mail, with a sword being apparently stuck in the dragon.” According to the report, “all three specimens are tattooed human skin.”

You had to admire Kipperman’s legwork and wonder why the Nuremberg and Dachau trials prosecutors, Thomas Dodd included, hadn’t been able to track down the lampshade, especially considering the enormous amount of publicity surrounding the object at the time. Might not someone have thought of asking Schmuhl, who lived in Ilse and Karl Koch’s villa during his Buchenwald tenure, if he had any idea what happened to such a sensational piece of evidence? Also worth asking would have been why Schmuhl, after years in the law enforcement business (he would go back to his warden’s job after the war and become the subject of a TV series called The Man Behind the Badge ), removed a critical piece of evidence from what was essentially a vast crime scene, and why he didn’t think to return it when the prosecution failed to produce the lampshade at the trials.

The picture in the newspaper was the closest Kipperman would get to the lampshade on the Table. By the middle 1990s, Schmuhl was long dead. Kipperman reached Henry Lange, author of the original Indianapolis Star piece, but the reporter knew nothing of what happened to the lampshade besides that Schmuhl had subsequently sold it to a collector who later disposed of it because “he couldn’t stand to look at it anymore.”

Kipperman pressed on, locating Schmuhl’s son, Robert, then living in Annapolis, Maryland. Robert Schmuhl confirmed that pieces of the lampshade had indeed been in his father’s house, that he’d seen them rolled up in a corner when he was growing up, along with a number of other souvenirs his father had brought home.

As for the lampshade, however, Robert Schmuhl, now deceased, could provide no information beyond what Kipperman had been told by Henry Lange. One day the thing was in his father’s house, then it was gone.

His hunt for the Buchenwald tattooed skin brought Kipperman into another conflict with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. “They have no interest in these things,” Kipperman said, inserting a VHS tape into a player. It was a copy of a ten-year-old local news show on which Kipperman appeared with Michael Berenbaum, who served as project director at the USHMM from 1988 to 1997, during which time he played a key role in the institution’s creation and assembly of its permanent collection. With a curriculum vitae that included being a professor of Holocaust studies at Clark University, teaching positions at Yale, George Washington, and Wesleyan, in addition to serving as president of the Shoah Visual History Foundation and overseeing the editing of the twenty-two-volume Encyclopædia Judaica, Berenbaum evidenced no patience for Kipperman’s claim that the Buchenwald human skin objects should be displayed at the Holocaust museum.

Читать дальше