This is bad news for psychologists, sociologists, economists and others who try to decipher human society through laboratory experiments. For both organisational and financial reasons, the vast majority of experiments are conducted either on individuals or on small groups of participants. Yet it is risky to extrapolate from small-group behaviour to the dynamics of mass societies. A nation of 100 million people functions in a fundamentally different way to a band of a hundred individuals.

Take, for example, the Ultimatum Game – one of the most famous experiments in behavioural economics. This experiment is usually conducted on two people. One of them gets $100, which he must divide between himself and the other participant in any way he wants. He may keep everything, split the money in half or give most of it away. The other player can do one of two things: accept the suggested division, or reject it outright. If he rejects the division, nobody gets anything.

Classical economic theories maintain that humans are rational calculating machines. They propose that most people will keep $99, and offer $1 to the other participant. They further propose that the other participant will accept the offer. A rational person offered a dollar will always say yes. What does he care if the other player gets $99?

Classical economists have probably never left their laboratories and lecture halls to venture into the real world. Most people playing the Ultimatum Game reject very low offers because they are ‘unfair’. They prefer losing a dollar to looking like suckers. Since this is how the real world functions, few people make very low offers in the first place. Most people divide the money equally, or give themselves only a moderate advantage, offering $30 or $40 to the other player.

The Ultimatum Game made a significant contribution to undermining classical economic theories and to establishing the most important economic discovery of the last few decades: Sapiens don’t behave according to a cold mathematical logic, but rather according to a warm social logic. We are ruled by emotions. These emotions, as we saw earlier, are in fact sophisticated algorithms that reflect the social mechanisms of ancient hunter-gatherer bands. If 30,000 years ago I helped you hunt a wild chicken and you then kept almost all the chicken to yourself, offering me just one wing, I did not say to myself: ‘Better one wing than nothing at all.’ Instead my evolutionary algorithms kicked in, adrenaline and testosterone flooded my system, my blood boiled, and I stamped my feet and shouted at the top of my voice. In the short term I may have gone hungry, and even risked a punch or two. But it paid off in the long term, because you thought twice before ripping me off again. We refuse unfair offers because people who meekly accepted unfair offers didn’t survive in the Stone Age.

Observations of contemporary hunter-gatherer bands support this idea. Most bands are highly egalitarian, and when a hunter comes back to camp carrying a fat deer, everybody gets a share. The same is true of chimpanzees. When one chimp kills a piglet, the other troop members will gather round him with outstretched hands, and usually they all get a piece.

In another recent experiment, the primatologist Frans de Waal placed two capuchin monkeys in two adjacent cages, so that each could see everything the other was doing. De Waal and his colleagues placed small stones inside each cage, and trained the monkeys to give them these stones. Whenever a monkey handed over a stone, he received food in exchange. At first the reward was a piece of cucumber. Both monkeys were very pleased with that, and happily ate their cucumber. After a few rounds de Waal moved to the next stage of the experiment. This time, when the first monkey surrendered a stone, he got a grape. Grapes are much more tasty than cucumbers. However, when the second monkey gave a stone, he still received a piece of cucumber. The second monkey, who was previously very happy with his cucumber, became incensed. He took the cucumber, looked at it in disbelief for a moment, and then threw it at the scientists in anger and began jumping and screeching loudly. He ain’t a sucker. 23

This hilarious experiment (which you can see for yourself on YouTube), along with the Ultimatum Game, has led many to believe that primates have a natural morality, and that equality is a universal and timeless value. People are egalitarian by nature, and unequal societies can never function well due to resentment and dissatisfaction.

But is that really so? These theories may work well on chimpanzees, capuchin monkeys and small hunter-gatherer bands. They also work well in the lab, where you test them on small groups of people. Yet once you observe the behaviour of human masses you discover a completely different reality. Most human kingdoms and empires were extremely unequal, yet many of them were surprisingly stable and efficient. In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh sprawled on comfortable cushions inside a cool and sumptuous palace, wearing golden sandals and gem-studded tunics, while beautiful maids popped sweet grapes into his mouth. Through the open window he could see the peasants in the fields, toiling in dirty rags under a merciless sun, and blessed was the peasant who had a cucumber to eat at the end of the day. Yet the peasants rarely revolted.

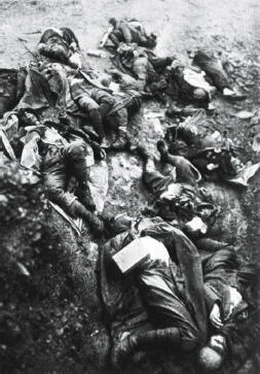

In 1740 King Frederick II of Prussia invaded Silesia, thus commencing a series of bloody wars that earned him his sobriquet Frederick the Great, turned Prussia into a major power and left hundreds of thousands of people dead, crippled or destitute. Most of Frederick’s soldiers were hapless recruits, subject to iron discipline and draconian drill. Not surprisingly, the soldiers lost little love on their supreme commander. As Frederick watched his troops assemble for the invasion, he told one of his generals that what struck him most about the scene was that ‘we are standing here in perfect safety, looking at 60,000 men – they are all our enemies, and there is not one of them who is not better armed and stronger than we are, and yet they all tremble in our presence, while we have no reason whatsoever to be afraid of them’. 24Frederick could indeed watch them in perfect safety. During the following years, despite all the hardships of war, these 60,000 armed men never revolted against him – indeed, many of them served him with exceptional courage, risking and even sacrificing their very lives.

Why did the Egyptian peasants and Prussian soldiers act so differently than we would have expected on the basis of the Ultimatum Game and the capuchin monkeys experiment? Because large numbers of people behave in a fundamentally different way than do small numbers. What would scientists see if they conducted the Ultimatum Game experiment on two groups of 1 million people each, who had to share $100 billion?

They would probably have witnessed strange and fascinating dynamics. For example, since 1 million people cannot make decisions collectively, each group might sprout a small ruling elite. What if one elite offers the other $10 billion, keeping $90 billion? The leaders of the second group might well accept this unfair offer, siphon most of the $10 billion into their Swiss bank accounts, while preventing rebellion among their followers with a combination of sticks and carrots. The leadership might threaten to severely punish dissidents forthwith, while promising the meek and patient everlasting rewards in the afterlife. This is what happened in ancient Egypt and eighteenth-century Prussia, and this is how things still work out in numerous countries around the world.

Such threats and promises often succeed in creating stable human hierarchies and mass-cooperation networks, as long as people believe that they reflect the inevitable laws of nature or the divine commands of God, rather than just human whims. All large-scale human cooperation is ultimately based on our belief in imagined orders. These are sets of rules that, despite existing only in our imagination, we believe to be as real and inviolable as gravity. ‘If you sacrifice ten bulls to the sky god, the rain will come; if you honour your parents, you will go to heaven; and if you don’t believe what I am telling you – you’ll go to hell.’ As long as all Sapiens living in a particular locality believe in the same stories, they all follow the same rules, making it easy to predict the behaviour of strangers and to organise mass-cooperation networks. Sapiens often use visual marks such as a turban, a beard or a business suit to signal ‘you can trust me, I believe in the same story as you’. Our chimpanzee cousins cannot invent and spread such stories, which is why they cannot cooperate in large numbers.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу