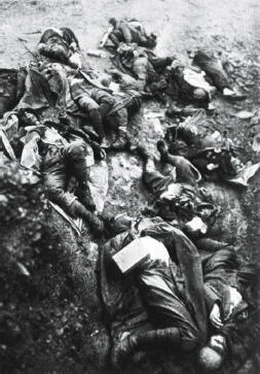

One day when John was just turning eighteen a dishevelled knight rode to the castle’s gate, and in a choked voice announced the news: Saladin has destroyed the crusader army at Hattin! Jerusalem has fallen! The Pope has declared a new crusade, promising eternal salvation to anyone who dies on it! All around, people looked shocked and worried, but John’s face lit up in an otherworldly glow and he proclaimed: ‘I am going to fight the infidels and liberate the Holy Land!’ Everyone fell silent for a moment, and then smiles and tears appeared on their faces. His mother wiped her eyes, gave John a big hug and told him how proud she was of him. His father gave him a mighty pat on the back, and said: ‘If only I was your age, son, I would join you. Our family’s honour is at stake – I am sure you won’t disappoint us!’ Two of his friends announced that they were coming too. Even John’s sworn rival, the baron on the other side of the river, paid a visit to wish him Godspeed.

As he left the castle, villagers came forth from their hovels to wave to him, and all the pretty girls looked longingly at the brave crusader setting off to fight the infidels. When he set sail from England and made his way through strange and distant lands – Normandy, Provence, Sicily – he was joined by bands of foreign knights, all with the same destination and the same faith. When the army finally disembarked in the Holy Land and waged battle with Saladin’s hosts, John was amazed to discover that even the wicked Saracens shared his beliefs. True, they were a bit confused, thinking that the Christians were the infidels and that the Muslims were obeying God’s will. Yet they too accepted the basic principle that those fighting for God and Jerusalem will go straight to heaven when they die.

In such a way, thread by thread, medieval civilisation spun its web of meaning, trapping John and his contemporaries like flies. It was inconceivable to John that all these stories were just figments of the imagination. Maybe his parents and uncles were wrong. But the minstrels too, and all his friends, and the village girls, the learned priest, the baron on the other side of the river, the Pope in Rome, the Provençal and Sicilian knights, and even the very Muslims – is it possible that they were all hallucinating?

And the years pass. As the historian watches, the web of meaning unravels and another is spun in its stead. John’s parents die, followed by all his siblings and friends. Instead of minstrels singing about the crusades, the new fashion is stage plays about tragic love affairs. The family castle burns to the ground and, when it is rebuilt, no trace is found of Grandpa Henry’s sword. The church windows shatter in a winter storm and the replacement glass no longer depicts Godfrey of Bouillon and the sinners in hell, but rather the great triumph of the king of England over the king of France. The local priest has stopped calling the Pope ‘our holy father’ – he is now referred to as ‘that devil in Rome’. In the nearby university scholars pore over ancient Greek manuscripts, dissect dead bodies and whisper quietly behind closed doors that perhaps there is no such thing as the soul.

And the years continue to pass. Where the castle once stood, there is now a shopping mall. In the local cinema they are screening Monty Python and the Holy Grail for the umpteenth time. In an empty church a bored vicar is overjoyed to see two Japanese tourists. He explains at length about the stained-glass windows, while they politely smile, nodding in complete incomprehension. On the steps outside a gaggle of teenagers are playing with their iPhones. They watch a new YouTube remix of John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’. ‘Imagine there’s no heaven,’ sings Lennon, ‘it’s easy if you try.’ A Pakistani street cleaner is sweeping the pavement, while a nearby radio broadcasts the news: the carnage in Syria continues, and the Security Council’s meeting has ended in an impasse. Suddenly a hole in time opens, a mysterious ray of light illuminates the face of one of the teenagers, who announces: ‘I am going to fight the infidels and liberate the Holy Land!’

Infidels and Holy Land? These words no longer carry any meaning for most people in today’s England. Even the vicar would probably think the teenager is having some sort of psychotic episode. In contrast, if an English youth decided to join Amnesty International and travel to Syria to protect the human rights of refugees, he will be seen as a hero. In the Middle Ages people would have thought he had gone bonkers. Nobody in twelfth-century England knew what human rights were. You want to travel to the Middle East and risk your life not in order to kill Muslims, but to protect one group of Muslims from another? You must be out of your mind.

That’s how history unfolds. People weave a web of meaning, believe in it with all their heart, but sooner or later the web unravels, and when we look back we cannot understand how anybody could have taken it seriously. With hindsight, going on crusade in the hope of reaching Paradise sounds like utter madness. With hindsight, the Cold War seems even madder. How come thirty years ago people were willing to risk nuclear holocaust because of their belief in a communist paradise? A hundred years hence, our belief in democracy and human rights might look equally incomprehensible to our descendants.

Dreamtime

Sapiens rule the world because only they can weave an intersubjective web of meaning: a web of laws, forces, entities and places that exist purely in their common imagination. This web allows humans alone to organise crusades, socialist revolutions and human rights movements.

Other animals may also imagine various things. A cat waiting to ambush a mouse might not see the mouse, but may well imagine the shape and even taste of the mouse. Yet to the best of our knowledge, cats are able to imagine only things that actually exist in the world, like mice. They cannot imagine things that they have never seen or smelled or tasted – such as the US dollar, Google corporation or the European Union. Only Sapiens can imagine such chimeras.

Consequently, whereas cats and other animals are confined to the objective realm and use their communication systems merely to describe reality, Sapiens use language to create completely new realities. During the last 70,000 years the intersubjective realities that Sapiens invented became ever more powerful, so that today they dominate the world. Will the chimpanzees, the elephants, the Amazon rainforests and the Arctic glaciers survive the twenty-first century? This depends on the wishes and decisions of intersubjective entities such as the European Union and the World Bank; entities that exist only in our shared imagination.

No other animal can stand up to us, not because they lack a soul or a mind, but because they lack the necessary imagination. Lions can run, jump, claw and bite. Yet they cannot open a bank account or file a lawsuit. And in the twenty-first century, a banker who knows how to file a lawsuit is far more powerful than the most ferocious lion in the savannah.

As well as separating humans from other animals, this ability to create intersubjective entities also separates the humanities from the life sciences. Historians seek to understand the development of intersubjective entities like gods and nations, whereas biologists hardly recognise the existence of such things. Some believe that if we could only crack the genetic code and map every neuron in the brain, we will know all of humanity’s secrets. After all, if humans have no soul, and if thoughts, emotions and sensations are just biochemical algorithms, why can’t biology account for all the vagaries of human societies? From this perspective, the crusades were territorial disputes shaped by evolutionary pressures, and English knights going to fight Saladin in the Holy Land were not that different from wolves trying to appropriate the territory of a neighbouring pack.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу