The humanities, in contrast, emphasise the crucial importance of intersubjective entities, which cannot be reduced to hormones and neurons. To think historically means to ascribe real power to the contents of our imaginary stories. Of course, historians don’t ignore objective factors such as climate changes and genetic mutations, but they give much greater importance to the stories people invent and believe. North Korea and South Korea are so different from one another not because people in Pyongyang have different genes to people in Seoul, or because the north is colder and more mountainous. It’s because the north is dominated by very different fictions.

Maybe someday breakthroughs in neurobiology will enable us to explain communism and the crusades in strictly biochemical terms. Yet we are very far from that point. During the twenty-first century the border between history and biology is likely to blur not because we will discover biological explanations for historical events, but rather because ideological fictions will rewrite DNA strands; political and economic interests will redesign the climate; and the geography of mountains and rivers will give way to cyberspace. As human fictions are translated into genetic and electronic codes, the intersubjective reality will swallow up the objective reality and biology will merge with history. In the twenty-first century fiction might thereby become the most potent force on earth, surpassing even wayward asteroids and natural selection. Hence if we want to understand our future, cracking genomes and crunching numbers is hardly enough. We must also decipher the fictions that give meaning to the world.

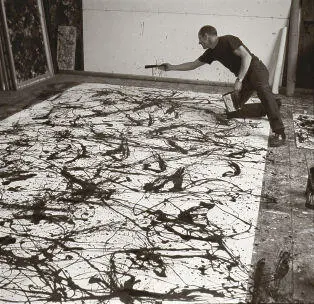

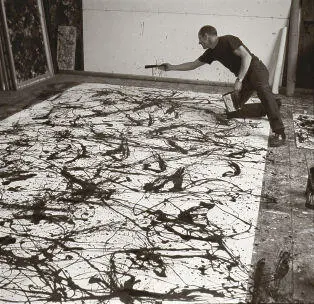

The Creator: Jackson Pollock in a moment of inspiration.

Rudy Burckhardt, photographer. Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, c .1905–1984. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © The Pollock–Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2016.

PART II

Homo Sapiens Gives Meaning to the World

What kind of world did humans create?

How did humans become convinced that they not only control the world, but also give it meaning?

How did humanism – the worship of humankind – become the most important religion of all?

Animals such as wolves and chimpanzees live in a dual reality. On the one hand, they are familiar with objective entities outside them, such as trees, rocks and rivers. On the other hand, they are aware of subjective experiences within them, such as fear, joy and desire. Sapiens, in contrast, live in triple-layered reality. In addition to trees, rivers, fears and desires, the Sapiens world also contains stories about money, gods, nations and corporations. As history unfolded, the impact of gods, nations and corporations grew at the expense of rivers, fears and desires. There are still many rivers in the world, and people are still motivated by their fears and wishes, but Jesus Christ, the French Republic and Apple Inc. have dammed and harnessed the rivers, and have learned to shape our deepest anxieties and yearnings.

Since new twenty-first-century technologies are likely to make such fictions only more potent, understanding our future requires understanding how stories about Christ, France and Apple have gained so much power. Humans think they make history, but history actually revolves around the web of stories. The basic abilities of individual humans have not changed much since the Stone Age. But the web of stories has grown from strength to strength, thereby pushing history from the Stone Age to the Silicon Age.

It all began about 70,000 years ago, when the Cognitive Revolution enabled Sapiens to start talking about things that existed only in their own imagination. For the following 60,000 years Sapiens wove many fictional webs, but these remained small and local. The spirit of a revered ancestor worshipped by one tribe was completely unknown to its neighbours, and seashells valuable in one locality became worthless once you crossed the nearby mountain range. Stories about ancestral spirits and precious seashells still gave Sapiens a huge advantage, because they allowed hundreds and sometimes even thousands of Sapiens to cooperate effectively, which was far more than Neanderthals or chimpanzees could do. Yet as long as Sapiens remained hunter-gatherers, they could not cooperate on a truly massive scale, because it was impossible to feed a city or a kingdom by hunting and gathering. Consequently the spirits, fairies and demons of the Stone Age were relatively weak entities.

The Agricultural Revolution, which began about 12,000 years ago, provided the necessary material base for enlarging and strengthening the intersubjective networks. Farming made it possible to feed thousands of people in crowded cities and thousands of soldiers in disciplined armies. However, the intersubjective webs then encountered a new obstacle. In order to preserve the collective myths and organise mass cooperation, the early farmers relied on the data-processing abilities of the human brain, which were strictly limited.

Farmers believed in stories about great gods. They built temples to their favourite god, held festivals in his honour, offered him sacrifices, and gave him lands, tithes and presents. In the first cities of ancient Sumer, about 6,000 years ago, the temples were not just centres of worship, but also the most important political and economic hubs. The Sumerian gods fulfilled a function analogous to modern brands and corporations. Today, corporations are fictional legal entities that own property, lend money, hire employees and initiate economic enterprises. In ancient Uruk, Lagash and Shurupak the gods functioned as legal entities that could own fields and slaves, give and receive loans, pay salaries and build dams and canals.

Since the gods never died, and since they had no children to fight over their inheritance, they gathered more and more property and power. An increasing number of Sumerians found themselves employed by the gods, taking loans from the gods, tilling the gods’ lands and owing taxes and tithes to the gods. Just as in present-day San Francisco John is employed by Google while Mary works for Microsoft, so in ancient Uruk one person was employed by the great god Enki while his neighbour worked for the goddess Inanna. The temples of Enki and Inanna dominated the Uruk skyline, and their divine logos branded buildings, products and clothes. For the Sumerians, Enki and Inanna were as real as Google and Microsoft are real for us. Compared to their predecessors – the ghosts and spirits of the Stone Age – the Sumerian gods were very powerful entities.

It goes without saying that the gods didn’t actually run their businesses, for the simple reason that they didn’t exist anywhere except in the human imagination. Day-to-day activities were managed by the temple priests (just as Google and Microsoft need to hire flesh-and-blood humans to manage their affairs). However, as the gods acquired more and more property and power, the priests could not cope. They may have represented the mighty sky god or the all-knowing earth goddess, but they themselves were fallible mortals. They had difficulty remembering all the lands belonging to the goddess Inanna, which of Inanna’s employees had received their salary already, which of the goddess’s tenants had failed to pay rent and what interest rate the goddess charged her debtors. This was one of the main reasons why in Sumer, like everywhere else around the world, human cooperation networks could not grow much even thousands of years after the Agricultural Revolution. There were no huge kingdoms, no extensive trade networks and no universal religions.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу