The Web of Meaning

People find it difficult to understand the idea of ‘imagined orders’ because they assume that there are only two types of realities: objective realities and subjective realities. In objective reality, things exist independently of our beliefs and feelings. Gravity, for example, is an objective reality. It existed long before Newton, and it affects people who don’t believe in it just as much as it affects those who do.

Subjective reality, in contrast, depends on my personal beliefs and feelings. Thus, suppose I feel a sharp pain in my head and go to the doctor. The doctor checks me thoroughly, but finds nothing wrong. So she sends me for a blood test, urine test, DNA test, X-ray, electrocardiogram, fMRI scan and a plethora of other procedures. When the results come in she announces that I am perfectly healthy, and I can go home. Yet I still feel a sharp pain in my head. Even though every objective test has found nothing wrong with me, and even though nobody except me feels the pain, for me the pain is 100 per cent real.

Most people presume that reality is either objective or subjective, and that there is no third option. Hence once they satisfy themselves that something isn’t just their own subjective feeling, they jump to the conclusion it must be objective. If lots of people believe in God; if money makes the world go round; and if nationalism starts wars and builds empires – then these things aren’t just a subjective belief of mine. God, money and nations must therefore be objective realities.

However, there is a third level of reality: the intersubjective level. Intersubjective entities depend on communication among many humans rather than on the beliefs and feelings of individual humans. Many of the most important agents in history are intersubjective. Money, for example, has no objective value. You cannot eat, drink or wear a dollar bill. Yet as long as billions of people believe in its value, you can use it to buy food, beverages and clothing. If the baker suddenly loses his faith in the dollar bill and refuses to give me a loaf of bread for this green piece of paper, it doesn’t matter much. I can just go down a few blocks to the nearby supermarket. However, if the supermarket cashiers also refuse to accept this piece of paper, along with the hawkers in the market and the salespeople in the mall, then the dollar will lose its value. The green pieces of paper will go on existing, of course, but they will be worthless.

Such things actually happen from time to time. On 3 November 1985 the Myanmar government unexpectedly announced that bank-notes of twenty-five, fifty and a hundred kyats were no longer legal tender. People were given no opportunity to exchange the notes, and savings of a lifetime were instantaneously turned into heaps of worthless paper. To replace the defunct notes, the government introduced new seventy-five-kyat bills, allegedly in honour of the seventy-fifth birthday of Myanmar’s dictator, General Ne Win. In August 1986, banknotes of fifteen kyats and thirty-five kyats were issued. Rumour had it that the dictator, who had a strong faith in numerology, believed that fifteen and thirty-five are lucky numbers. They brought little luck to his subjects. On 5 September 1987 the government suddenly decreed that all thirty-five and seventy-five notes were no longer money.

The value of money is not the only thing that might evaporate once people stop believing in it. The same can happen to laws, gods and even entire empires. One moment they are busy shaping the world, and the next moment they no longer exist. Zeus and Hera were once important powers in the Mediterranean basin, but today they lack any authority because nobody believes in them. The Soviet Union could once destroy the entire human race, yet it ceased to exist at the stroke of a pen. At 2 p.m. on 8 December 1991, in a state dacha near Viskuli, the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus signed the Belavezha Accords, which stated that ‘We, the Republic of Belarus, the Russian Federation and Ukraine, as founding states of the USSR that signed the union treaty of 1922, hereby establish that the USSR as a subject of international law and a geopolitical reality ceases its existence.’ 25And that was that. No more Soviet Union.

It is relatively easy to accept that money is an intersubjective reality. Most people are also happy to acknowledge that ancient Greek gods, evil empires and the values of alien cultures exist only in the imagination. Yet we don’t want to accept that our God, our nation or our values are mere fictions, because these are the things that give meaning to our lives. We want to believe that our lives have some objective meaning, and that our sacrifices matter to something beyond the stories in our head. Yet in truth the lives of most people have meaning only within the network of stories they tell one another.

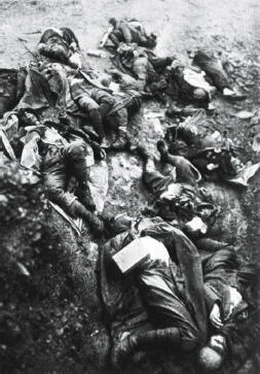

Signing the Belavezha Accords. Pen touches paper – and abracadabra! The Soviet Union disappears.

© NOVOSTI/AFP/Getty Images.

Meaning is created when many people weave together a common network of stories. Why does a particular action – such as getting married in church, fasting on Ramadan or voting on election day – seem meaningful to me? Because my parents also think it is meaningful, as do my brothers, my neighbours, people in nearby cities and even the residents of far-off countries. And why do all these people think it is meaningful? Because their friends and neighbours also share the same view. People constantly reinforce each other’s beliefs in a self-perpetuating loop. Each round of mutual confirmation tightens the web of meaning further, until you have little choice but to believe what everyone else believes.

Yet over decades and centuries the web of meaning unravels and a new web is spun in its place. To study history means to watch the spinning and unravelling of these webs, and to realise that what seems to people in one age the most important thing in life becomes utterly meaningless to their descendants.

In 1187 Saladin defeated the crusader army at the Battle of Hattin and conquered Jerusalem. In response the Pope launched the Third Crusade to recapture the holy city. Imagine a young English nobleman named John, who left home to fight Saladin. John believed that his actions had an objective meaning. He believed that if he died on the crusade, after death his soul would ascend to heaven, where it would enjoy everlasting celestial joy. He would have been horrified to learn that the soul and heaven are just stories invented by humans. John wholeheartedly believed that if he reached the Holy Land, and if some Muslim warrior with a big moustache brought an axe down on his head, he would feel an unbearable pain, his ears would ring, his legs would crumble under him, his field of vision would turn black – and the very next moment he would see brilliant light all around him, he would hear angelic voices and melodious harps, and radiant winged cherubs would beckon him through a magnificent golden gate.

John had a very strong faith in all this, because he was enmeshed within an extremely dense and powerful web of meaning. His earliest memories were of Grandpa Henry’s rusty sword, hanging in the castle’s main hall. Ever since he was a toddler John had heard stories of Grandpa Henry who died on the Second Crusade and who is now resting with the angels in heaven, watching over John and his family. When minstrels visited the castle, they usually sang about the brave crusaders who fought in the Holy Land. When John went to church, he enjoyed looking at the stained-glass windows. One showed Godfrey of Bouillon riding a horse and impaling a wicked-looking Muslim on his lance. Another showed the souls of sinners burning in hell. John listened attentively to the local priest, the most learned man he knew. Almost every Sunday, the priest explained – with the help of well-crafted parables and hilarious jokes – that there was no salvation outside the Catholic Church, that the Pope in Rome was our holy father and that we always had to obey his commands. If we murdered or stole, God would send us to hell; but if we killed infidel Muslims, God would welcome us to heaven.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу