Though the history of writing is full of similar mishaps, in most cases writing did enable officials to organise the state much more efficiently than before. Indeed, even the disaster of the Great Leap Forward didn’t topple the Chinese Communist Party from power. The catastrophe was caused by the ability to impose written fantasies on reality, but exactly the same ability allowed the party to paint a rosy picture of its successes and hold on to power tenaciously.

Written language may have been conceived as a modest way of describing reality, but it gradually became a powerful way to reshape reality. When official reports collided with objective reality, it was often reality that had to give way. Anyone who has ever dealt with the tax authorities, the educational system or any other complex bureaucracy knows that the truth hardly matters. What’s written on your form is far more important.

Holy Scriptures

Is it true that when text and reality collide, reality sometimes has to give way? Isn’t it just a common but exaggerated slander of bureaucratic systems? Most bureaucrats – whether serving pharaoh or Mao Zedong – were reasonable people, and surely would have made the following argument: ‘We use writing to describe the reality of fields, canals and granaries. If the description is accurate, we make realistic decisions. If the description is inaccurate, it causes famines and even rebellions. Then we, or the administrators of some future regime, learn from the mistake, and strive to produce more truthful descriptions. So over time, our documents are bound to become ever more precise.’

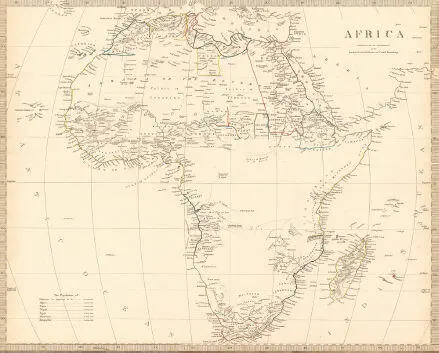

That’s true to some extent, but it ignores an opposite historical dynamic. As bureaucracies accumulate power, they become immune to their own mistakes. Instead of changing their stories to fit reality, they can change reality to fit their stories. In the end, external reality matches their bureaucratic fantasies, but only because they forced reality to do so. For example, the borders of many African countries disregard river lines, mountain ranges and trade routes, split historical and economic zones unnecessarily, and ignore local ethnic and religious identities. The same tribe may find itself riven between several countries, whereas one country may incorporate splinters of numerous rival clans. Such problems bedevil countries all over the world, but in Africa they are particularly acute because modern African borders don’t reflect the wishes and struggles of local nations. They were drawn by European bureaucrats who never set foot in Africa.

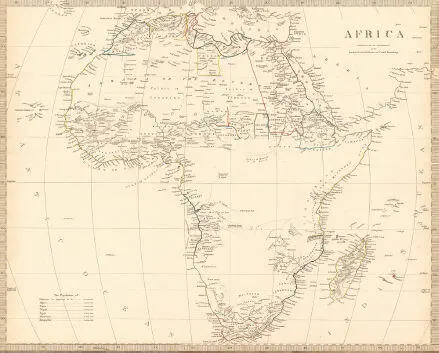

In the late nineteenth century, several European powers laid claim to African territories. Fearing that conflicting claims might lead to an all-out European war, the concerned parties got together in Berlin in 1884, and divided Africa as if it were a pie. Back then, much of the African interior was terra incognita to Europeans. The British, French and Germans had accurate maps of Africa’s coastal regions, and knew precisely where the Niger, the Congo and the Zambezi empty into the ocean. However, they knew little about the course these rivers took inland, about the kingdoms and tribes that lived along their banks, and about local religion, history and geography. This hardly mattered to the European diplomats. They took out an empty map of Africa, spread it over a well-polished Berlin table, sketched lines here and there, and divided the continent between them.

When the Europeans penetrated the African interior, armed with the agreed-upon map, they discovered that many of the borders drawn in Berlin hardly did justice to the geographic, economic and ethnic reality of Africa. However, to avoid renewed clashes, the invaders stuck to their agreements, and these imaginary lines became the actual borders of European colonies. During the second half of the twentieth century, as the European empires disintegrated and the colonies gained their independence, the new countries accepted the colonial borders, fearing that the alternative would be endless wars and conflicts. Many of the difficulties faced by present-day African countries stem from the fact that their borders make little sense. When the written fantasies of European bureaucracies encountered the African reality, reality was forced to surrender. 5

The modern educational system provides numerous other examples of reality bowing down to written records. When measuring the width of my desk, the yardstick I am using matters little. My desk remains the same width regardless of whether I say it is 200 centimetres or 78.74 inches. However, when bureaucracies measure people, the yardsticks they choose make all the difference. When schools began assessing people according to precise marks, the lives of millions of students and teachers changed dramatically. Marks are a relatively new invention. Hunter-gatherers were never marked for their achievements, and even thousands of years after the Agricultural Revolution, few educational establishments used precise marks. A medieval apprentice cobbler did not receive at the end of the year a piece of paper saying he has got an A on shoelaces but a C minus on buckles. An undergraduate in Shakespeare’s day left Oxford with one of only two possible results – with a degree, or without one. Nobody thought of giving one student a final mark of 74 and another student 88. 6

A European map of Africa from the mid-nineteenth century. The Europeans knew very little about the African interior, which did not prevent them from dividing the continent and drawing its borders.

© Antiqua Print Gallery/Alamy Stock Photo.

Only the mass educational systems of the industrial age began using precise marks on a regular basis. Since both factories and government ministries became accustomed to thinking in the language of numbers, schools followed suit. They started to gauge the worth of each student according to his or her average mark, whereas the worth of each teacher and principal was judged according to the school’s overall average. Once bureaucrats adopted this yardstick, reality was transformed.

Originally, schools were supposed to focus on enlightening and educating students, and marks were merely a means of measuring success. But naturally enough, schools soon began focusing on getting high marks. As every child, teacher and inspector knows, the skills required to get high marks in an exam are not the same as a true understanding of literature, biology or mathematics. Every child, teacher and inspector also knows that when forced to choose between the two, most schools will go for the marks.

The power of written records reached its apogee with the appearance of holy scriptures. Priests and scribes in ancient civilisations got used to seeing documents as guidebooks for reality. At first, the texts told them about the reality of taxes, fields and granaries. But as the bureaucracy gained power, so the texts gained authority. Priests wrote down not just the god’s property list, but also the god’s deeds, commandments and secrets. The resulting scriptures purported to describe reality in its entirety, and generations of scholars became accustomed to looking for all the answers in the pages of the Bible, the Qur’an or the Vedas.

In theory, if some holy book misrepresented reality, its disciples would sooner or later find it out, and the text would lose its authority. Abraham Lincoln said you cannot deceive everybody all the time. Well, that’s wishful thinking. In practice, the power of human cooperation networks rests on a delicate balance between truth and fiction. If you distort reality too much, it will weaken you, and you will not be able to compete against more clear-sighted rivals. On the other hand, you cannot organise masses of people effectively without relying on some fictional myths. So if you stick to pure reality, without mixing any fiction with it, few people would follow you.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу