People have many material, social and mental needs. It is far from clear that peasants in ancient Egypt enjoyed more love or better social relations than their hunter-gatherer ancestors, and in terms of nutrition, health and child mortality it seems that life was actually worse. A document dated c. 1850 BC from the reign of Amenemhat III – the pharaoh who created Lake Fayum – tells of a well-to-do man called Dua-Khety who took his son Pepy to school, so that he could learn to be a scribe. On the way to school, Dua-Khety portrayed the miserable life of peasants, labourers, soldiers and artisans, so as to encourage Pepy to devote all his energy to studying, thereby escaping the destiny of most humans.

According to Dua-Khety, the life of a landless field labourer is full of hardship and misery. Dressed in mere tatters, he works all day till his fingers are covered in blisters. Then pharaoh’s officials come and take him away to do forced labour. In return for all his hard work he receives only sickness as payment. Even if he makes it home alive, he will be completely worn out and ruined. The fate of the landholding peasant is hardly better. He spends his days carrying water in buckets from the river to the field. The heavy load bends his shoulders and covers his neck with festering swellings. In the morning he has to water his plot of leeks, in the afternoon his date palms and in the evening his coriander field. Eventually he drops down and dies. 8The text might exaggerate things on purpose, but not by much. Pharaonic Egypt was the most powerful kingdom of its day, but for the simple peasant all that power meant taxes and forced labour rather than clinics and social security services.

This was not a uniquely Egyptian defect. Despite all the immense achievements of the Chinese dynasties, the Muslim empires and the European kingdoms, even in AD 1850 the life of the average person was not better – and might actually have been worse – than the lives of archaic hunter-gatherers. In 1850 a Chinese peasant or a Manchester factory hand worked longer hours than their hunter-gatherer ancestors; their jobs were physically harder and mentally less fulfilling; their diet was less balanced; hygiene conditions were incomparably worse; and infectious diseases were far more common.

Suppose you were given a choice between the following two vacation packages:

Stone Age package : On day one we will hike for ten hours in a pristine forest, setting camp for the night in a clearing by a river. On day two we will canoe down the river for ten hours, camping on the shores of a small lake. On day three we will learn from the native people how to fish in the lake and how to find mushrooms in the nearby woods.

Modern proletarian package : On day one we will work for ten hours in a polluted textile factory, passing the night in a cramped apartment block. On day two we will work for ten hours as cashiers in the local department store, going back to sleep in the same apartment block. On day three we will learn from the native people how to open a bank account and fill out mortgage forms.

Which package would you choose?

Hence when we come to evaluate human cooperation networks, it all depends on the yardsticks and viewpoint we adopt. Are we judging pharaonic Egypt in terms of production, nutrition or perhaps social harmony? Do we focus on the aristocracy, the simple peasants, or the pigs and crocodiles? History isn’t a single narrative, but thousands of alternative narratives. Whenever we choose to tell one, we are also choosing to silence others.

Human cooperative networks usually judge themselves by yardsticks of their own invention, and not surprisingly, they often give themselves high marks. In particular, human networks built in the name of imaginary entities such as gods, nations and corporations normally judge their success from the viewpoint of the imaginary entity. A religion is successful if it follows divine commandments to the letter; a nation is glorious if it promotes the national interest; and a corporation thrives if it makes a lot of money.

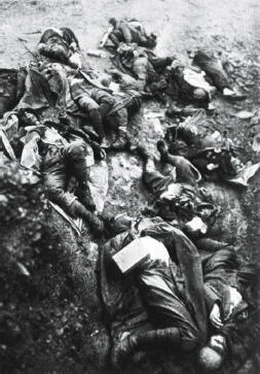

When examining the history of any human network, it is therefore advisable to stop from time to time and look at things from the perspective of some real entity. How do you know if an entity is real? Very simple – just ask yourself, ‘Can it suffer?’ When people burn down the temple of Zeus, Zeus doesn’t suffer. When the euro loses its value, the euro doesn’t suffer. When a bank goes bankrupt, the bank doesn’t suffer. When a country suffers a defeat in war, the country doesn’t really suffer. It’s just a metaphor. In contrast, when a soldier is wounded in battle, he really does suffer. When a famished peasant has nothing to eat, she suffers. When a cow is separated from her newborn calf, she suffers. This is reality.

Of course suffering might well be caused by our belief in fictions. For example, belief in national and religious myths might cause the outbreak of war, in which millions lose their homes, their limbs and even their lives. The cause of war is fictional, but the suffering is 100 per cent real. This is exactly why we should strive to distinguish fiction from reality.

Fiction isn’t bad. It is vital. Without commonly accepted stories about things like money, states or corporations, no complex human society can function. We can’t play football unless everyone believes in the same made-up rules, and we can’t enjoy the benefits of markets and courts without similar make-believe stories. But the stories are just tools. They should not become our goals or our yardsticks. When we forget that they are mere fiction, we lose touch with reality. Then we begin entire wars ‘to make a lot of money for the corporation’ or ‘to protect the national interest’. Corporations, money and nations exist only in our imagination. We invented them to serve us; how come we find ourselves sacrificing our lives in their service?

Stories serve as the foundations and pillars of human societies. As history unfolded, stories about gods, nations and corporations grew so powerful that they began to dominate objective reality. Believing in the great god Sobek, the Mandate of Heaven or the Bible enabled people to build Lake Fayum, the Great Wall of China and Chartres Cathedral. Unfortunately, blind faith in these stories meant that human efforts frequently focused on increasing the glory of fictional entities such as gods and nations, instead of bettering the lives of real sentient beings.

Does this analysis still hold true today? At first sight, it seems that modern society is very different from the kingdoms of ancient Egypt or medieval China. Hasn’t the rise of modern science changed the basic rules of the human game? Wouldn’t it be true to say that despite the ongoing importance of traditional myths, modern social systems rely increasingly on objective scientific theories such as the theory of evolution, which simply did not exist in ancient Egypt or medieval China?

We could of course argue that scientific theories are a new kind of myth, and that our belief in science is no different from the ancient Egyptians’ belief in the great god Sobek. Yet the comparison doesn’t hold water. Sobek existed only in the collective imagination of his devotees. Praying to Sobek helped cement the Egyptian social system, thereby enabling people to build dams and canals that prevented floods and droughts. Yet the prayers themselves didn’t raise or lower the Nile’s water level by a millimetre. In contrast, scientific theories are not just a way to bind people together. It is often said that God helps those who help themselves. This is a roundabout way of saying that God doesn’t exist, but if our belief in Him inspires us to do something ourselves – it helps. Antibiotics, unlike God, help even those who don’t help themselves. They cure infections whether you believe in them or not.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу