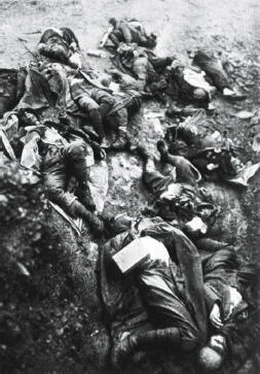

The Pope selling indulgences for money (from a Protestant pamphlet).

Woodcut from ‘Passional Christi und Antichristi’ by Philipp Melanchthon, published in 1521, Cranach, Lucas (1472–1553) (studio of) © Private Collection/Bridgeman Images.

From a historical perspective, the spiritual journey is always tragic, for it is a lonely path fit for individuals rather than for entire societies. Human cooperation requires firm answers rather than just questions, and those who foam against stultified religious structures end up forging new structures in their place. It happened to the dualists, whose spiritual journeys became religious establishments. It happened to Martin Luther, who after challenging the laws, institutions and rituals of the Catholic Church found himself writing new law books, founding new institutions and inventing new ceremonies. It happened even to Buddha and Jesus. In their uncompromising quest for the truth they subverted the laws, rituals and structures of traditional Hinduism and Judaism. But eventually more laws, more rituals and more structures were created in their name than in the name of any other person in history.

Counterfeiting God

Now that we have a better understanding of religion, we can go back to examining the relationship between religion and science. There are two extreme interpretations for this relationship. One view says that science and religion are sworn enemies, and that modern history was shaped by the life-and-death struggle of scientific knowledge against religious superstition. With time, the light of science dispelled the darkness of religion, and the world became increasingly secular, rational and prosperous. However, though some scientific findings certainly undermine religious dogmas, this is not inevitable. For example, Muslim dogma holds that Islam was founded by the prophet Muhammad in seventh-century Arabia, and there is ample scientific evidence supporting this.

More importantly, science always needs religious assistance in order to create viable human institutions. Scientists study how the world functions, but there is no scientific method for determining how humans ought to behave. Science tells us that humans cannot survive without oxygen. However, is it okay to execute criminals by asphyxiation? Science doesn’t know how to answer such a question. Only religions provide us with the necessary guidance.

Hence every practical project scientists undertake also relies on religious insights. Take, for example, the building of the Three Gorges Dam over the Yangtze River. When the Chinese government decided to build the dam in 1992, physicists could calculate what pressures the dam would have to withstand, economists could forecast how much money it would probably cost, while electrical engineers could predict how much electricity it would produce. However, the government needed to take additional factors into account. Building the dam flooded huge territories containing many villages and towns, thousands of archaeological sites, and unique landscapes and habitats. More than 1 million people were displaced and hundreds of species were endangered. It seems that the dam directly caused the extinction of the Chinese river dolphin. No matter what you personally think about the Three Gorges Dam, it is clear that building it was an ethical rather than a purely scientific issue. No physics experiment, no economic model and no mathematical equation can determine whether generating thousands of megawatts and making billions of yuan is more valuable than saving an ancient pagoda or the Chinese river dolphin. Consequently, China cannot function on the basis of scientific theories alone. It requires some religion or ideology, too.

Some jump to the opposite extreme, and say that science and religion are completely separate kingdoms. Science studies facts, religion speaks about values, and never the twain shall meet. Religion has nothing to say about scientific facts, and science should keep its mouth shut concerning religious convictions. If the Pope believes that human life is sacred, and abortion is therefore a sin, biologists can neither prove nor refute this claim. As a private individual, each biologist is welcome to argue with the Pope. But as a scientist, the biologist cannot enter the fray.

This approach may sound sensible, but it misunderstands religion. Though science indeed deals only with facts, religion never confines itself to ethical judgements. Religion cannot provide us with any practical guidance unless it makes some factual claims too, and here it may well collide with science. The most important segments of many religious dogmas are not their ethical principles, but rather factual statements such as ‘God exists’, ‘the soul is punished for its sins in the afterlife’, ‘the Bible was written by a deity rather than by humans’, ‘the Pope is never wrong’. These are all factual claims. Many of the most heated religious debates, and many of the conflicts between science and religion, involve such factual claims rather than ethical judgements.

Take abortion, for example. Devout Christians often oppose abortion, whereas many liberals support it. The main bone of contention is factual rather than ethical. Both Christians and liberals believe that human life is sacred, and that murder is a heinous crime. But they disagree about certain biological facts: does human life begin at the moment of conception, at the moment of birth or at some middle point? Indeed, some human cultures maintain that life doesn’t begin even at birth. According to the !Kung of the Kalahari Desert and to various Inuit groups in the Arctic, human life begins only after the person is given a name. When an infant is born people wait for some time before naming it. If they decide not to keep the baby (either because it suffers from some deformity or because of economic difficulties), they kill it. Provided they do so before the naming ceremony, it is not considered murder. 2People from such cultures might well agree with liberals and Christians that human life is sacred and that murder is a terrible crime, yet they support infanticide.

When religions advertise themselves, they tend to emphasise their beautiful values. But God often hides in the small print of factual statements. The Catholic religion markets itself as the religion of universal love and compassion. How wonderful! Who can object to that? Why, then, are not all humans Catholic? Because when you read the small print, you discover that Catholicism also demands blind obedience to a pope ‘who never makes mistakes’ even when he orders us to go on crusades and burn heretics at the stake. Such practical instructions are not deduced solely from ethical judgements. Rather, they result from conflating ethical judgements with factual statements.

When we leave the ethereal sphere of philosophy and observe historical realities, we find that religious stories almost always include three parts:

1. Ethical judgements, such as ‘human life is sacred’.

2. Factual statements, such as ‘human life begins at the moment of conception’.

3. A conflation of the ethical judgements with the factual statements, resulting in practical guidelines such as ‘you should never allow abortion, even a single day after conception’.

Science has no authority or ability to refute or corroborate the ethical judgements religions make. But scientists do have a lot to say about religious factual statements. For example, biologists are more qualified than priests to answer factual questions such as ‘Do human fetuses have a nervous system one week after conception? Can they feel pain?’

To make things clearer, let us examine in depth a real historical example that you rarely hear about in religious commercials, but that had a huge social and political impact in its time. In medieval Europe, the popes enjoyed far-reaching political authority. Whenever a conflict erupted somewhere in Europe, they claimed the authority to decide the issue. To establish their claim to authority, they repeatedly reminded Europeans of the Donation of Constantine. According to this story, on 30 March 315 the Roman emperor Constantine signed an official decree granting Pope Sylvester I and his heirs perpetual control of the western part of the Roman Empire. The popes kept this precious document in their archive, and used it as a powerful propaganda tool whenever they faced opposition from ambitious princes, quarrelsome cities or rebellious peasants.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу