Hence according to our best scientific knowledge, the Leviticus injunctions against homosexuality reflect nothing grander than the biases of a few priests and scholars in ancient Jerusalem. Though science cannot decide whether people ought to obey God’s commands, it has many relevant things to say about the provenance of the Bible. If Ugandan politicians think that the power that created the cosmos, the galaxies and the black holes becomes terribly upset whenever two Homo sapiens males have a bit of fun together, then science can help disabuse them of this rather bizarre notion.

Holy Dogma

In truth, it is not always easy to separate ethical judgements from factual statements. Religions have the nagging tendency to turn factual statements into ethical judgements, thereby creating terrible confusion and obfuscating what should have been relatively simple debates. Thus the factual statement ‘God wrote the Bible’ all too often mutates into the ethical injunction ‘you ought to believe that God wrote the Bible’. Merely believing in this factual statement becomes a virtue, whereas doubting it becomes a terrible sin.

Conversely, ethical judgements often hide within them factual statements that people don’t bother to mention, because they think they have been proven beyond doubt. Thus the ethical judgement ‘human life is sacred’ (which science cannot test) may shroud the factual statement ‘every human has an eternal soul’ (which is open for scientific debate). Similarly, when American nationalists proclaim that ‘the American nation is sacred’, this seemingly ethical judgement is in fact predicated on factual statements such as ‘the USA has spearheaded most of the moral, scientific and economic advances of the last few centuries’. Whereas it is impossible to scientifically scrutinise the claim that the American nation is sacred, once we unpack this judgement we may well examine scientifically whether the USA has indeed been responsible for a disproportionate share of moral, scientific and economic breakthroughs.

This has led some philosophers, such as Sam Harris, to argue that science can always resolve ethical dilemmas, because human values always hide within them some factual statements. Harris thinks all humans share a single supreme value – minimising suffering and maximising happiness – and all ethical debates are factual arguments concerning the most efficient way to maximise happiness. 5Islamic fundamentalists want to reach heaven in order to be happy, liberals believe that increasing human liberty maximises happiness, and German nationalists think that everyone would be better off if they only allowed Berlin to run this planet. According to Harris, Islamists, liberals and nationalists have no ethical dispute; they have a factual disagreement about how best to realise their common goal.

Yet even if Harris is right, and even if all humans cherish happiness, in practice it would be extremely difficult to use this insight to decide ethical disputes, particularly because we have no scientific definition or measurement of happiness. Consider the case of the Three Gorges Dam. Even if we agree that the ultimate aim of the project is to make the world a happier place, how can we tell whether generating cheap electricity contributes more to global happiness than protecting traditional lifestyles or saving the rare Chinese river dolphin? As long as we haven’t deciphered the mysteries of consciousness, we cannot develop a universal measurement for happiness and suffering, and we don’t know how to compare the happiness and suffering of different individuals, let alone different species. How many units of happiness are generated when a billion Chinese enjoy cheaper electricity? How many units of misery are produced when an entire dolphin species becomes extinct? Indeed, are happiness and misery mathematical entities that can be added or subtracted in the first place? Eating ice cream is enjoyable. Finding true love is more enjoyable. Do you think that if you just eat enough ice cream, the accumulated pleasure could ever equal the rapture of true love?

Consequently, although science has much more to contribute to ethical debates than we commonly think, there is a line it cannot cross, at least not yet. Without the guiding hand of some religion, it is impossible to maintain large-scale social orders. Even universities and laboratories need religious backing. Religion provides the ethical justification for scientific research, and in exchange gets to influence the scientific agenda and the uses of scientific discoveries. Hence you cannot understand the history of science without taking religious beliefs into account. Scientists seldom dwell on this fact, but the Scientific Revolution itself began in one of the most dogmatic, intolerant and religious societies in history.

The Witch Hunt

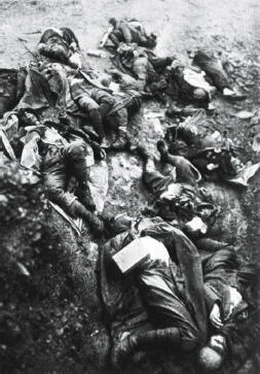

We often associate science with the values of secularism and tolerance. If so, early modern Europe is the last place you would have expected a scientific revolution. Europe in the days of Columbus, Copernicus and Newton had the highest concentration of religious fanatics in the world, and the lowest level of tolerance. The luminaries of the Scientific Revolution lived in a society that expelled Jews and Muslims, burned heretics wholesale, saw a witch in every cat-loving elderly lady and started a new religious war every full moon.

If you travelled to Cairo or Istanbul around 1600, you would find there a multicultural and tolerant metropolis, where Sunnis, Shiites, Orthodox Christians, Catholics, Armenians, Copts, Jews and even the occasional Hindu lived side by side in relative harmony. Though they had their share of disagreements and riots, and though the Ottoman Empire routinely discriminated against people on religious grounds, it was a liberal paradise compared with Europe. If you then travelled to contemporary Paris or London, you would find cities awash with religious extremism, in which only those belonging to the dominant sect could live. In London they killed Catholics, in Paris they killed Protestants, the Jews had long been driven out, and nobody in his right mind would dream of letting any Muslims in. And yet, the Scientific Revolution began in London and Paris rather than in Cairo and Istanbul.

It is customary to tell the history of modernity as a struggle between science and religion. In theory, both science and religion are interested above all in the truth, and because each upholds a different truth, they are doomed to clash. In fact, neither science nor religion cares that much about the truth, hence they can easily compromise, coexist and even cooperate.

Religion is interested above all in order. It aims to create and maintain the social structure. Science is interested above all in power. It aims to acquire the power to cure diseases, fight wars and produce food. As individuals, scientists and priests may give immense importance to the truth; but as collective institutions, science and religion prefer order and power over truth. They can therefore make good bedfellows. The uncompromising quest for truth is a spiritual journey, which can seldom remain within the confines of either religious or scientific establishments.

It would accordingly be far more correct to view modern history as the process of formulating a deal between science and one particular religion – namely, humanism. Modern society believes in humanist dogmas, and uses science not in order to question these dogmas, but rather in order to implement them. In the twenty-first century the humanist dogmas are unlikely to be replaced by pure scientific theories. However, the covenant linking science and humanism may well crumble, and give way to a very different kind of deal, between science and some new post-humanist religion. We will dedicate the next two chapters to understanding the modern covenant between science and humanism. The third and final part of the book will then explain why this covenant is disintegrating, and what new deal might replace it.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу