And even if Santino doesn’t remember the past and doesn’t imagine the future, does it mean he lacks self-consciousness? After all, we ascribe self-consciousness to humans even when they are not busy remembering the past or dreaming about the future. For example, when a human mother sees her toddler wandering onto a busy road, she doesn’t stop to think about either past or future. Just like the mother elephant, she too just races to save her child. Why not say about her what we say about the elephant, namely that ‘when the mother rushed to save her baby from the oncoming danger, she did it without any self-consciousness. She was merely driven by a momentary urge’?

Similarly, consider a young couple kissing passionately on their first date, a soldier charging into heavy enemy fire to save a wounded comrade, or an artist drawing a masterpiece in a frenzy of brushstrokes. None of them stops to contemplate the past or the future. Does it mean they lack self-consciousness, and that their state of being is inferior to that of a politician giving an election speech about his past achievements and future plans?

The Clever Horse

In 2010 scientists conducted an unusually touching rat experiment. They locked a rat in a tiny cage, placed the cage within a much larger cell and allowed another rat to roam freely through that cell. The caged rat gave out distress signals, which caused the free rat also to exhibit signs of anxiety and stress. In most cases, the free rat proceeded to help her trapped companion, and after several attempts usually succeeded in opening the cage and liberating the prisoner. The researchers then repeated the experiment, this time placing chocolate in the cell. The free rat now had to choose between either liberating the prisoner, or enjoying the chocolate all by herself. Many rats preferred to first free their companion and share the chocolate (though quite a few behaved more selfishly, proving perhaps that some rats are meaner than others).

Sceptics dismissed these results, arguing that the free rat liberated the prisoner not out of empathy, but simply in order to stop the annoying distress signals. The rats were motivated by the unpleasant sensations they felt, and they sought nothing grander than ending these sensations. Maybe. But we could say exactly the same thing about us humans. When I donate money to a beggar, am I not reacting to the unpleasant sensations that the sight of the beggar causes me to feel? Do I really care about the beggar, or do I simply want to feel better myself? 16

In essence, we humans are not that different from rats, dogs, dolphins or chimpanzees. Like them, we too have no soul. Like us, they too have consciousness and a complex world of sensations and emotions. Of course, every animal has its unique traits and talents. Humans too have their special gifts. We shouldn’t humanise animals needlessly, imagining that they are just a furrier version of ourselves. This is not only bad science, but it also prevents us from understanding and valuing other animals on their terms.

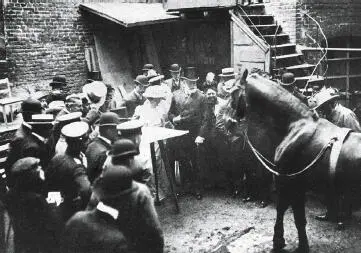

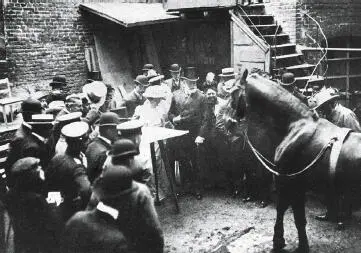

In the early 1900s, a horse called Clever Hans became a German celebrity. Touring Germany’s towns and villages, Hans showed off a remarkable grasp of the German language, and an even more remarkable mastery of mathematics. When asked, ‘Hans, what is four times three?’ Hans tapped his hoof twelve times. When shown a written message asking, ‘What is twenty minus eleven?’ Hans tapped nine times, with commendable Prussian precision.

In 1904 the German board of education appointed a special scientific commission headed by a psychologist to look into the matter. The thirteen members of the commission – which included a circus manager and a veterinarian – were convinced this must be a scam, but despite their best efforts they couldn’t uncover any fraud or subterfuge. Even when Hans was separated from his owner, and complete strangers presented him with the questions, Hans still got most of the answers right.

In 1907 the psychologist Oskar Pfungst began another investigation that finally revealed the truth. It turned out that Hans got the answers right by carefully observing the body language and facial expressions of his interlocutors. When Hans was asked what is four times three, he knew from past experience that the human was expecting him to tap his hoof a given number of times. He began tapping, while closely monitoring the human. As Hans approached the correct number of taps the human became more and more tense, and when Hans tapped the right number, the tension reached its peak. Hans knew how to recognise this by the human’s body posture and the look on the human’s face. He then stopped tapping, and watched how tension was replaced by amazement or laughter. Hans knew he had got it right.

Clever Hans is often given as an example of the way humans erroneously humanise animals, ascribing to them far more amazing abilities than they actually possess. In fact, however, the lesson is just the opposite. The story demonstrates that by humanising animals we usually underestimate animal cognition and ignore the unique abilities of other creatures. As far as maths goes, Hans was hardly a genius. Any eight-year-old kid could do much better. However, in his ability to deduce emotions and intentions from body language, Hans was a true genius. If a Chinese person were to ask me in Mandarin what is four times three, there is no way that I could correctly tap my foot twelve times simply by observing facial expressions and body language. Clever Hans enjoyed this ability because horses normally communicate with each other through body language. What was remarkable about Hans, however, is that he could use the method to decipher the emotions and intentions not only of his fellow horses, but also of unfamiliar humans.

Clever Hans on stage in 1904.

© 2004 TopFoto.

If animals are so clever, why don’t horses harness humans to carts, rats conduct experiments on us, and dolphins make us jump through hoops? Homo sapiens surely has some unique ability that enables it to dominate all the other animals. Having dismissed the overblown notions that Homo sapiens exists on an entirely different plain from other animals, or that humans possess some unique essence like soul or consciousness, we can finally climb down to the level of reality and examine the particular physical or mental abilities that give our species its edge.

Most studies cite tool production and intelligence as particularly important for the ascent of humankind. Though other animals also produce tools, there is little doubt that humans far surpass them in that field. Things are a bit less clear with regard to intelligence. An entire industry is devoted to defining and measuring intelligence but is a long way from reaching a consensus. Luckily, we don’t have to enter into that minefield, because no matter how one defines intelligence, it is quite clear that neither intelligence nor toolmaking by themselves can account for the Sapiens conquest of the world. According to most definitions of intelligence, a million years ago humans were already the most intelligent animals around, as well as the world’s champion toolmakers, yet they remained insignificant creatures with little impact on the surrounding ecosystem. They were obviously lacking some key feature other than intelligence and toolmaking.

Perhaps humankind eventually came to dominate the planet not because of some elusive third key ingredient, but due simply to the evolution of even higher intelligence and even better toolmaking abilities? It doesn’t seem so, because when we examine the historical record, we don’t see a direct correlation between the intelligence and toolmaking abilities of individual humans and the power of our species as a whole. Twenty thousand years ago, the average Sapiens probably had higher intelligence and better toolmaking skills than the average Sapiens of today. Modern schools and employers may test our aptitudes from time to time but, no matter how badly we do, the welfare state always guarantees our basic needs. In the Stone Age natural selection tested you every single moment of every single day, and if you flunked any of its numerous tests you were pushing up the daisies in no time. Yet despite the superior toolmaking abilities of our Stone Age ancestors, and despite their sharper minds and far more acute senses, 20,000 years ago humankind was much weaker than it is today.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу