For this you take more groups of rats, who have never participated in the test before. You inject each group with a particular chemical, which you suspect to be the hoped-for antidepressant. You throw the rats into the water. If rats injected with chemical A struggle for only fifteen minutes before becoming depressed, you can cross out A on your list. If rats injected with chemical B go on thrashing for twenty minutes, you can tell the CEO and the shareholders that you might have just hit the jackpot.

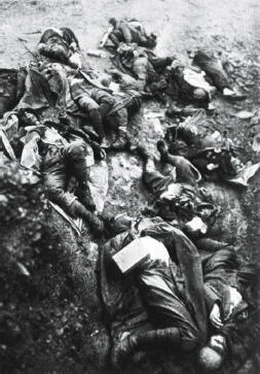

Left: A hopeful rat struggling to escape the glass tube. Right: An apathetic rat floating in the glass tube, having lost all hope.

Adapted from Weiss, J.M., Cierpial, M.A. & West, C.H., ‘Selective breeding of rats for high and low motor activity in a swim test: toward a new animal model of depression’, Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 61:49–66 (1998).

Sceptics could object that this entire description needlessly humanises rats. Rats experience neither hope nor despair. Sometimes rats move quickly and sometimes they stand still, but they never feel anything. They are driven only by non-conscious algorithms. Yet if so, what’s the point of all these experiments? Psychiatric drugs are aimed to induce changes not just in human behaviour, but above all in human feeling . When customers go to a psychiatrist and say, ‘Doctor, give me something that will lift me out of this depression,’ they don’t want a mechanical stimulant that will cause them to flail about while still feeling blue. They want to feel cheerful. Conducting experiments on rats can help corporations develop such a magic pill only if they presuppose that rat behaviour is accompanied by human-like emotions. And indeed, this is a common presupposition in psychiatric laboratories. 10

The Self-Conscious Chimpanzee

Another attempt to enshrine human superiority accepts that rats, dogs and other animals have consciousness, but argues that, unlike humans, they lack self-consciousness. They may feel depressed, happy, hungry or satiated, but they have no notion of self, and they are not aware that the depression or hunger they feel belongs to a unique entity called ‘I’.

This idea is as common as it is opaque. Obviously, when a dog feels hungry, he grabs a piece of meat for himself rather than serve food to another dog. Let a dog sniff a tree watered by the neighbourhood dogs, and he will immediately know whether it smells of his own urine, of the neighbour’s cute Labrador’s or of some stranger’s. Dogs react very differently to their own odour and to the odours of potential mates and rivals. 11So what does it mean that they lack self-consciousness?

A more sophisticated version of the argument says that there are different levels of self-consciousness. Only humans understand themselves as an enduring self that has a past and a future, perhaps because only humans can use language in order to contemplate their past experiences and future actions. Other animals exist in an eternal present. Even when they seem to remember the past or plan for the future, they are in fact reacting only to present stimuli and momentary urges. 12For instance, a squirrel hiding nuts for the winter doesn’t really remember the hunger he felt last winter, nor is he thinking about the future. He just follows a momentary urge, oblivious to the origins and purpose of this urge. That’s why even very young squirrels, who haven’t yet lived through a winter and hence cannot remember winter, nevertheless cache nuts during the summer.

Yet it is unclear why language should be a necessary condition for being aware of past or future events. The fact that humans use language to do so is hardly a proof. Humans also use language to express their love or their fear, but other animals may well experience and even express love and fear non-verbally. Indeed, humans themselves are often aware of past and future events without verbalising them. Especially in dream states, we can be aware of entire non-verbal narratives – which upon waking we struggle to describe in words.

Various experiments indicate that at least some animals – including birds such as parrots and scrub jays – do remember individual incidents and consciously plan for future eventualities. 13However, it is impossible to prove this beyond doubt, because no matter how sophisticated a behaviour an animal exhibits, sceptics can always claim that it results from unconscious algorithms in its brain rather than from conscious images in its mind.

To illustrate this problem consider the case of Santino, a male chimpanzee from the Furuvik Zoo in Sweden. To relieve the boredom in his compound Santino developed an exciting hobby: throwing stones at visitors to the zoo. In itself, this is hardly unique. Angry chimpanzees often throw stones, sticks and even excrement. However, Santino was planning his moves in advance. During the early morning, long before the zoo opened for visitors, Santino collected projectiles and placed them in a heap, without showing any visible signs of anger. Guides and visitors soon learned to be wary of Santino, especially when he was standing near his pile of stones, hence he had increasing difficulties in finding targets.

In May 2010, Santino responded with a new strategy. In the early morning he took bales of straw from his sleeping quarters and placed them close to the compound’s wall, where visitors usually gather to watch the chimps. He then collected stones and hid them under the straw. An hour or so later, when the first visitors approached, Santino kept his cool, showing no signs of irritation or aggression. Only when his victims were within range did Santino suddenly grab the stones from their hiding place and bombard the frightened humans, who would scuttle in all directions. In the summer of 2012 Santino sped up the arms race, caching stones not only under straw bales, but also in tree trunks, buildings and any other suitable hiding place.

Yet even Santino doesn’t satisfy the sceptics. How can we be certain that at 7 a.m., when Santino goes about secreting stones here and there, he is imagining how fun it will be to pelt the visiting humans at noon? Maybe Santino is driven by some non-conscious algorithm, just like a young squirrel hiding nuts ‘for winter’ even though he has never experienced winter? 14

Similarly, say the sceptics, a male chimpanzee attacking a rival who hurt him weeks earlier isn’t really avenging the old insult. He is just reacting to a momentary feeling of anger, the cause of which is beyond him. When a mother elephant sees a lion threatening her calf, she rushes forward and risks her life not because she remembers that this is her beloved offspring whom she has been nurturing for months; rather, she is impelled by some unfathomable sense of hostility towards the lion. And when a dog jumps for joy when his owner comes home, the dog isn’t recognising the man who fed and cuddled him from infancy. He is simply overwhelmed by an unexplained ecstasy. 15

We cannot prove or disprove any of these claims, because they are in fact variations on the Problem of Other Minds. Since we aren’t familiar with any algorithm that requires consciousness, anything an animal does can be seen as the product of non-conscious algorithms rather than of conscious memories and plans. So in Santino’s case too, the real question concerns the burden of proof. What is the most likely explanation for Santino’s behaviour? Should we assume that he is consciously planning for the future, and anyone who disagrees should provide some counter-evidence? Or is it more reasonable to think that the chimpanzee is driven by a non-conscious algorithm, and all he consciously feels is a mysterious urge to place stones under bales of straw?

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу