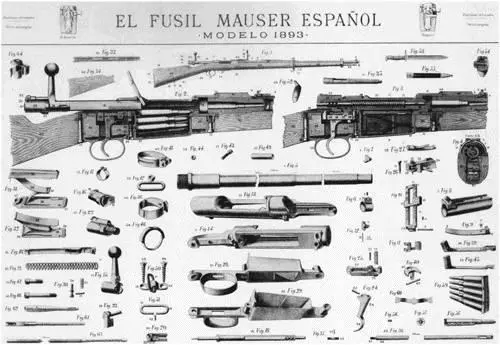

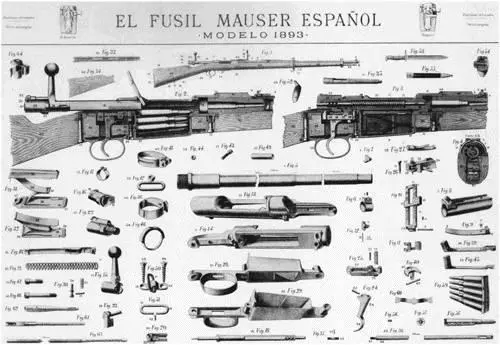

“The Spanish Hornet”: the Spanish Mauser, Model 1893, which bedeviled American troops in Cuba.

The Americans had their own bolt-action weapon, the magazine-fed Krag-Jorgensen, officially named “U.S. magazine Rifle (or Carbine), .30 caliber, Model 1896.” While the Krag was a step up from the past, the Norwegian-designed gun wasn’t in the same league as the Mauser. Worse, most of the regular U.S. Army troops on the battlefield were carrying the 1873 Trapdoor Springfields, which fired dangerously obsolete, shorter-range .45–70 black powder cartridges. Yes, those are the same rifles Custer’s men used at Little Bighorn. The clouds of smoke they shed were “bullet magnets” letting the enemy know where they were. Let me tell you, I don’t recommend announcing your position like that when there are snipers around.

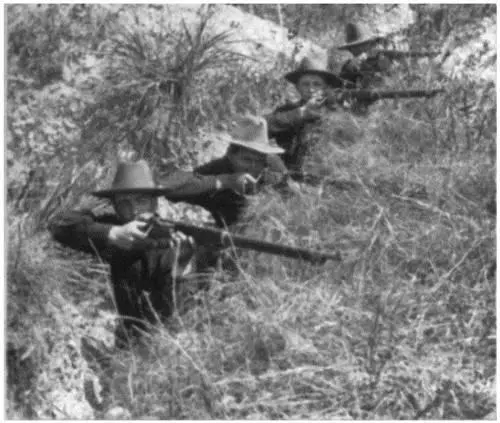

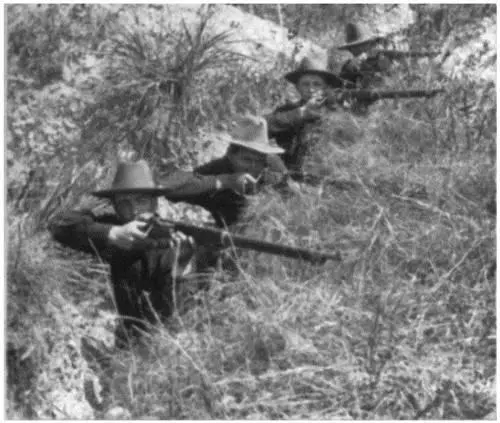

“In the trenches on San Juan Hill, Cuba.” American Krag rifles (shown here) proved inferior, launching the quest that lead to the M1903.

Library of Congress

Before arriving in Cuba, Roosevelt had decided the trapdoor Springfield was “antiquated” and “almost useless in the battle.” He wasn’t too sure about the Krags, either. He had shelled out money from his own pocket to buy his officers some of his favorite Winchester repeaters, but his force was still hopelessly outgunned.

And stuck, with only one way to go—up the hill, toward the bullets.

“Spanish fire,” remembered Roosevelt later, “swept the whole field of battle up to the edge of the river, and man after man in our ranks fell dead or wounded.” The Mauser’s smokeless powder made it harder for the Americans to find targets. “The Mauser bullets drove in sheets through the trees and the tall jungle grass, making a peculiar whirring or rustling sound,” said Roosevelt. “Some of the bullets seemed to pop in the air, so that we thought they were explosive; and, indeed, many of those which were coated with brass did explode, in the sense that the brass coat was ripped off, making a thin plate of hard metal with a jagged edge, which inflicted a ghastly wound.”

Lines of American soldiers, led by Roosevelt, climbed the hills like streams of ants into the carpets of Spanish bullets. It was a slow-motion charge, with the Americans fighting not just the Spanish bullets and the slope, but also the intense heat. Some fell; others dropped for cover. The assault crawled along.

With his men hugging the ground, an American officer stood up and paced in the open to inspire his troops. “Captain, a bullet is sure to hit you,” protested one of his men. The officer took his cigarette out of his mouth, blew out a smoke cloud, and laughed. “Sergeant, the Spanish bullet isn’t made that will kill me!”

Roosevelt witnessed what happened next: “As he turned on his heel, a bullet struck him in the mouth and came out at the back of his head; so that even before he fell his wild and gallant soul had gone out into the darkness.”

Reporter Richard Harding Davis recalled, “They walked to greet death at every step, many of them, as they advanced, sinking suddenly or pitching forward and disappearing in the high grass, but the others waded on, stubbornly, forming a thin blue line that kept creeping higher and higher up the hill. It was as inevitable as the rising tide. It was a miracle of self-sacrifice, a triumph of bulldog courage, which one watched breathless with wonder.”

For all their bravery, the assault might have failed except for an ace of a weapon. A battery of three hand-cranked Colt M-1895 Gatling guns swept the Spanish-held heights with sheets of .30-caliber gunfire, covering the advance and clearing paths for the American assault.

The drum of the guns was like no other sound on the battlefield. The sound cheered the Americans even as it mowed down the Spanish. The Gatlings would lay down an impressive 18,000 rounds in support of the U.S. troops that day.

The assault picked up steam. Roosevelt was grazed by bullets twice. He waved his bloody hand in the air to rally his troops forward. Finally the Spanish, realizing they were about to be overrun, retreated from their Kettle Hill fortifications.

Forty yards from the crest, a wire barrier blocked Teddy’s stallion. Roosevelt spun out of the saddle like the rancher he once was, climbed over the wire, and dashed to the top. For a moment, he stood atop Kettle Hill nearly alone, his troops climbing to meet him.

Over on San Juan Heights, the main force sent the Spanish reeling. Roosevelt reinforced Kettle Hill, surveying a horrible sight.

The Spanish fortifications, Roosevelt recalled, were “filled with dead bodies in the light blue and white uniform of the Spanish regular army.” He came across very few wounded, as “most of the fallen had little holes in their heads from which their brains were oozing.”

Suddenly, two Spanish soldiers popped up from the piles of bodies, leveled their Mausers at Roosevelt, and fired from ten yards away.

They missed. Roosevelt jerked his Colt revolver and held it at hip level as they turned to run. He fired twice, missing the first and killing the second.

A reporter watching the Americans consolidate their positions atop San Juan Heights at about 2 p.m. remembered the scene: “They drove the yellow silk flags of the cavalry and the Stars and Stripes of their country into the soft earth of the trenches, and then sank down and looked back at the road they had climbed and swung their hats in the air.” The reporter heard a faint, tired cheer. The battle was won, and over.

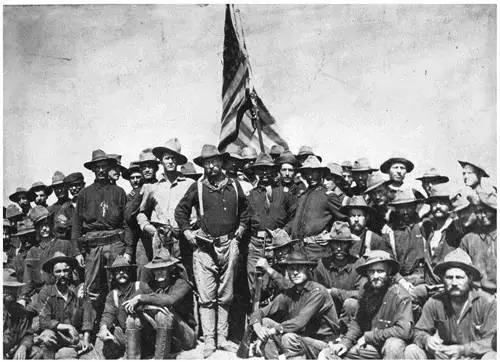

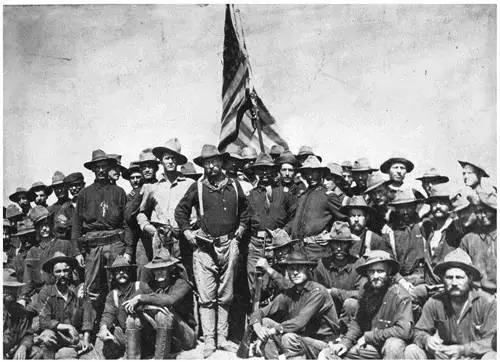

Colonel Roosevelt and the Rough Riders at the top of San Juan Heights, after weathering the storm of Spanish Mauser fire. TR’s holster contains a Colt revolver that was recovered from the wreck of the Maine .

Library of Congress

American losses were immense: over two hundred dead and nearly another twelve hundred wounded. The Spanish lost 215 dead and another 376 wounded. The real story of the numbers, though, is this: the American force was 15,000; the Spanish started with 750. The fact that the Spanish could hold off such a large force at all is a testament not only to their weapons but their courage and skill as warriors.

The charges up Kettle Hill and San Juan Heights alone did not win the Spanish-American War. But it had numerous effects. With the hills taken, Santiago could not be held. The admiral who headed the Spanish fleet had been sitting on his ass for days, debating whether to go out and face the American fleet or not. Now he had no choice. His ships sailed out to their destruction in Santiago Bay July 3. The city of Santiago surrendered July 17; game over.

The Spanish sued for peace. The Treaty of Paris was signed on August 12, and the Americans were granted authority over the Spanish colonies of Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, and Cuba. Just like that, the United States was an international power. The epic images of Roosevelt and the Rough Riders’ actions that day were celebrated by the press. His fame propelled him into the governorship of New York State in a few short months. Then came the vice presidency, and after William McKinley’s assassination in September 1901, the presidency itself, at the tender age of forty-two.

The episode also marked a turning point in American guns: the shift from antiquated military rifles to cutting-edge, modern weapons that could dominate the battlefield. The road ahead would continue to be filled with curves and detours, but change would no longer be resisted on the grounds that proven technology was still too new.

Читать дальше