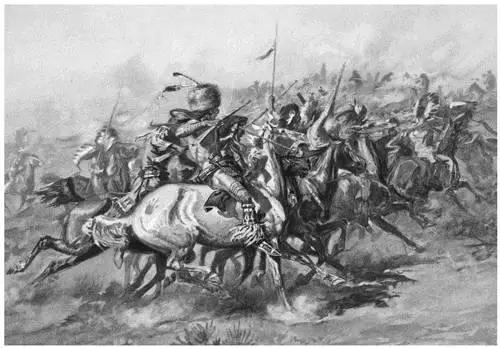

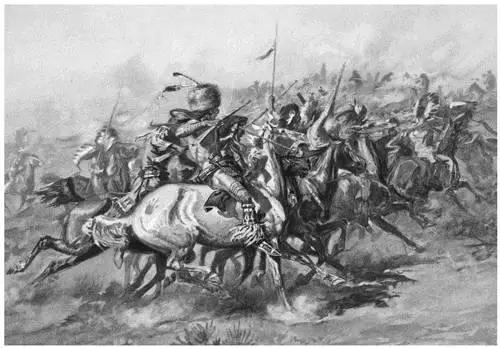

An artist’s depiction of the Battle of Little Bighorn. The Native American force employed more repeaters—such as the Winchester held by the Indian warrior at front—than Custer’s U.S. Army troops.

Library of Congress

As the Indians’ momentum increased, they used “battlefield pickups” and corpse-stripping of U.S. Army weapons and ammo to boost their firepower. “By this time,” said Red Hawk, “the Indians were taking the guns and cartridges of the dead soldiers and putting these to use.”

The Indians had begun the day armed with a plethora of weapons, including a favorite Native American rifle, the Winchester. The repeater gave them a powerful edge when the fighting got closer. “The Indians at the Little Bighorn used at least 47 different types of firearms against the 7th Cavalry,” reports Doug Scott, a prominent historian of the battle who has studied its archaeology. “The Henry, Winchester Model 1866, and [Winchester] Model 1873 were used in abundance.” Archeological analyses performed by Scott and others in recent decades has estimated that roughly 25 percent of the Indian warriors were armed with repeating Henrys or Winchester 1866 or 1873 models; another 25 percent were armed with single-shot rifles and muzzleloaders of various types, and the remaining half used traditional war implements like clubs, lances, and bows and arrows. The Indians had obtained the repeaters through trade, U.S. government clearance sales, raids, and battlefield pickups.

The complete annihilation of Custer and his troops at Little Bighorn was the biggest victory ever achieved by Native Americans against the U.S. Army. It also marked a milestone in the long climax of the Indian Wars, which finally ended at Wounded Knee in 1890. There, troops of the same Seventh Cavalry massacred one hundred and fifty or more Indian men, women, and children.

Debates have raged among historians and firearms buffs for decades around Custer’s mistakes, over alternative histories of the Bighorn battle, and about what difference various guns might have made. It’s possible Custer wouldn’t have stood much of a chance no matter what weapons he had, given the overwhelming number of Indian warriors he faced.

At the risk of armchair quarterbacking, let’s suggest one gun that Custer should have taken along, a revolutionary weapon that might have saved him and his troops.

It was the Gatling gun, a two-man, hand-cranked, rapid-fire “machine gun” that could fire hundreds of bullet rounds a minute. First used during the Civil War, the weapon could spit bullets out at a furious pace. Custer had access to a battery of six Gatlings. Though heavy, the guns could be broken down, packed onto mules or horses, and hauled, with some difficulty, over the rough terrain. The downside was they had a tendency to jam and otherwise malfunction, and they could roll over and shatter to pieces while being handled on hilly inclines.

But it wasn’t the Gatling’s awesome firepower that would have saved Custer. It was the fact that the bulky Gatlings, even when disassembled for portability, would have slowed his march to Little Bighorn long enough for his forces to consolidate. Reinforcements would have arrived in time. Custer would have hours to spare to formulate a coherent plan of action.

But time was the reason Custer left them behind in the first place. He figured they’d slow him down.

On second thought, maybe there was no hope for Custer at all. He was in too much of a hurry to meet his fate.

Dubbed “the gun that won the West,” the Winchester Model 1873 was an instant hit, destined to be a long-running best-seller for the company. The first cartridge it fired was a .44–40 Winchester center fire round, which proved particularly popular with people who owned revolvers in the same caliber. Winchester soon produced rifles in other calibers, making it possible for more gun owners to use the same bullets for their long gun and their pistol.

Other models followed. Winchester developed the 1876 with an enlarged and strengthened receiver, which allowed for larger and more powerful cartridges. Eventually available in a series of calibers ranging from .40–60 on up to .50–95 Express, the gun packed enough wallop to make it suitable for buffalo hunting. The 1876 and the 1886 that followed were versatile and powerful rifles, and straddled the transition from black powder to smokeless.

Winchester lever-action rifles became the prized possession of ranchers, movie stars, and presidents alike. The Winchester Model 1892 Lever-Action Repeater was the favorite of sharpshooter Annie Oakley and tagged along in Admiral Robert Peary’s baggage on a trek to the North Pole. Winchester sold a million of those guns. The Model 1894 was an even hotter seller, with more than 7 million produced in its different forms, making it the number one sporting rifle in history. Though it was first built to fire black powder rounds, it switched easily to new smokeless cartridges. In the United States, the Winchester 94 .30–30 combo became synonymous with “deer rifle.” You can still buy one new, fresh from the factory.

But my all-time favorite Winchester repeater has to be the Model 1892. If you’ve watched only John Wayne movies, you’ve probably seen the gun. It has an oversized loop trigger guard that looks like a miniature metal lasso under the stock. Unlike the 1876 and 1886 models, the 1892 was made to handle shorter rounds, again allowing a frontiersman to carry the same bullets for pistol and rifle.

For years, a friend of mine had a fine example of an 1892 sitting in his weapons vault. This particular version was a specially made Winchester John Wayne Commemorative edition. It had special engraving on the metal and a silver indicia on the stock showing the Duke’s profile. Any time I’d go over to the vault, just about my favorite thing would be to take that rifle and rack it. I’d work the action like I was riding with the Duke himself.

One day, we were in there talking, and I went over to the gun. My friend looked at me a little funny, so I stopped and backed away.

“Take it,” he told me. “It’s yours.”

“Huh?”

“You like that gun so much,” he insisted. “Take it.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

I did. And I’ve enjoyed it ever since.

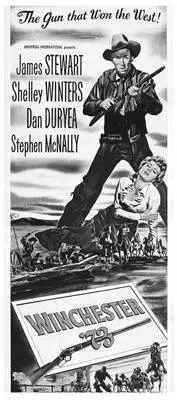

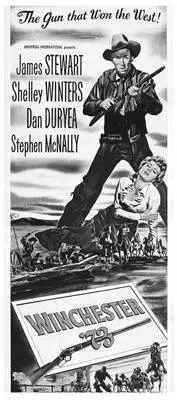

You can’t make a Western without a Winchester. Above, John Wayne takes aim in El Dorado; below, in the hands of Jimmy Stewart in Winchester ’73.

Paramount Pictures

In the early morning hours of Valentine’s Day, 1884, a young politician sat at the bedside of his dying wife, trying to make sense of the way joy had suddenly turned to tragedy over the past twenty-four hours. He had returned home to New York City through a terrible fog and storm after receiving a wire that his wife had given birth to their first child. Now he was shocked to find his wife dying of kidney failure, then known as Bright’s Disease. Downstairs, his mother was in the final stages of typhoid fever.

His daughter was healthy, but both his mother and wife would die that same day.

Devastated and utterly alone, the young man left politics and New York. Wandering the American West in search of a new life, he settled into the life of a rancher and outdoorsman in the badlands of Dakota Territory.

Читать дальше