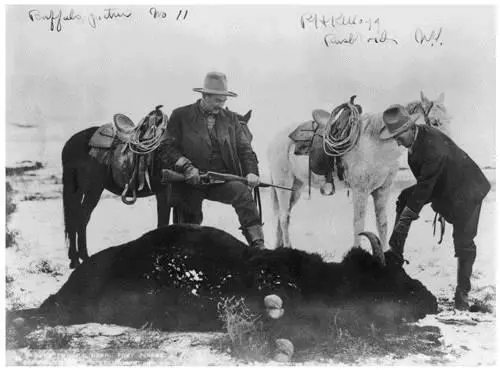

The big Sharps was capable of bringing down bison at distances approaching half a mile. It “shoots today and kills tomorrow,” Native Americans said of the Sharps. “The Sharps was a different kind of gun,” wrote Keith McCafferty in Field & Stream in 1997. “Originally a target rifle of great accuracy and crushing power, Sharps rifles became the tools of choice for those who came to slaughter the great buffalo herds. There was no nobility in what the hide hunters did. It was wretched, fast-money work that they themselves despised, and it represents a dark page in our history.”

The orgy of wholesale buffalo slaughter surged after the Civil War and peaked in the 1870s and 1880s, powered by the Sharps and other accurate, high-powered long-range hunting rifles firing big metallic cartridges. A single “Big Fifty” Sharps .50–90 rifle owned by legendary buffalo hunter J. Wright Mooar was believed to have dispatched more than 22,000 buffalo.

Bison weren’t the only things you could take with a Big Fifty. A legendary sniper named Billy Dixon made what came to be known as “the Shot of the Century” with a Sharps. He was at a trading outpost in Texas named Adobe Walls, on June 27, 1874, when the settlement came under fierce attack by as many as a thousand Indian warriors. One woman and twenty-eight white men—including a young Bat Masterson—huddled inside the fort walls and five buildings, fending off the attack. Indians pounded on doors and windows with their clubs and rifle butts as defenders held them off with Winchesters and pistols.

Finally repulsed, the Indians were gathering for a fresh round of attacks on the second day of the siege when Dixon borrowed a Sharps buffalo gun from the post’s well-stocked arsenal. He squeezed off a shot that killed a mounted Indian warrior from a distance measured two weeks later by a team of U.S. Army surveyors at 1,538 yards. The shot apparently broke the morale of the Native American strike force. They abandoned the siege two days later in a major psychological defeat. Worse, the failed attack convinced the military to step up their campaign against the natives. The Red River War followed in 1874–75; at the end of the conflict, the survivors of the defeated tribes were relocated to Oklahoma reservations.

The other big buffalo gun in the West was the classic Remington Rolling Block rifle, a single-shot breechloader with a simple but extremely strong mechanism. On a gun with a rolling block, the breach is sealed by a lock or breechblock that rotates backwards for loading. To load, the hammer is pulled back to full cock. The breechblock is then pulled back, opening the chamber so the cartridge can be put in. Push the breechblock back into place, and you’re ready to fire.

The extremely durable weapon could handle the large charges and calibers needed to knock down buffalo and other large game. The range and accuracy of both the Remington and the Sharps were an important asset, since they allowed hunters to shoot from a good distance. The idea was to get precision kills without alerting the rest of the herd to what was going on. It was an idea that applies with some modifications to all long-range shooting, not just buffalo hunting.

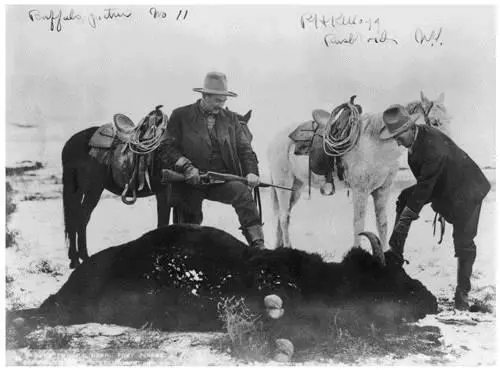

A buffalo hunter and his Winchester Model 1895.

Library of Congress

By 1875, the southern buffalo herd had been all but exterminated—and in that year, partly as a consequence, the mighty Comanche surrendered at last. America’s surviving buffalo now roamed only over the Dakotas, Montana, and Wyoming, where they helped the northern Plains Indians resist the onrush of whites and their ways. These last great buffalo-hunting grounds would host the final acts of the Indian Wars. Ironically, it was the native tribes who reaped the advantage of American firearm innovation in the most famous confrontation in that end game: Custer’s Last Stand.

When the Battle of Little Bighorn began on June 25, 1876, at 4:15 p.m. near a riverside Indian settlement in eastern Montana, George Armstrong Custer had 210 mounted troops and scouts of the U.S. Army Seventh Cavalry under his command. They were largely armed with single-shot 1873 “Trapdoor” Springfield carbines.

Less than sixty minutes later, Custer and all of his men were gone. Their deaths were serenaded by the staccato crackle of gunfire from Winchester repeating rifles—in the hands of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors.

Guided by poor intel and his own bad judgment, Custer’s plan was to attack the Indian settlement quickly. A separate force under his command would engage from another direction while a third detachment blocked the escape route through a nearby valley. Custer apparently aimed to induce the Indian warriors to sue for peace by taking their women and children as hostages and human shields. He figured, according to author Evan S. Connell, that the Indians “would be obliged to surrender, because if they started to fight, they would be shooting their own families.”

But Custer never got his hostages. Instead, he was cut off by a multi-tribal strike force of perhaps 1,500 combat-seasoned Indian fighters. He was hugely outnumbered, and, just as importantly, outgunned.

The “Trapdoor” Springfield carbines in the hands and saddles of Custer’s men were recycled weapons from the Civil War. Faced with tons of surplus muzzle-loading rifle-muskets when the Civil War ended, the Army decided to modify the guns by cutting into the rear of the barrel and installing a breechblock, chamber, and “trapdoor” bolt, a system into which metal cartridges could be loaded fairly quickly. Under perfect conditions, a trooper might get twelve to fifteen shots off in a minute.

Under perfect conditions.

The U.S. Army continued to use the single-shot Trapdoor Springfield well into the Spanish American War, despite all evidence of their shortcomings. Army planners were not only cheap, but stuck in the past.

To be fair, the Springfields did have some upsides. The carbines were fairly rugged, fired a good-sized bullet, and were accurate at long range. They could throw a .45-caliber, 405-grain bullet as far as 600 yards or more with fine results. But as it happened, the battle climax at Little Bighorn was fought at relatively close range. Like most U.S. Army troops in those days, Custer’s men were not intensively drilled in marksmanship, and were prone to shoot high, especially when aiming downhill. They had trouble reloading quickly under pressure. The guns themselves suffered a kind of combat fatigue: the Springfields were known to jam, overheat, and get fouled with residue during fighting.

Custer’s problems were magnified by his tactics and the terrain. The brushy landscape hid the size of the Indian force. His impulsive race to attack the huge Indian village took him out of range of reinforcements. He split up his command repeatedly on the battlefield, and launched his attack without much in the way of reconnaissance.

According to Indians who fought in the battle, Custer’s “last stand” was actually a series of five individual stands made by groups of cavalrymen, as Custer’s lines repeatedly collapsed up the hill in ten-minute stages. At one point the dismounted Army troops held a fairly continuous line along a half-mile backbone in the hill. But everything changed when the Lakota’s warrior chief, Crazy Horse, led a sudden, surprise mounted charge through their ranks.

“Right among them we rode,” said a Little Bighorn vet named Thunder Bear, “shooting them down as in a buffalo drive.” Daniel White Thunder remembered, “As soon as the soldiers on foot had marched over the ridge,” he and his fellow warriors stampeded Custer’s horses “by waving their blankets and making a terrible noise.” The horses carried away most of the cavalry’s reserve ammunition. Red Hawk described a scene of mass confusion: “The dust was thick and we could hardly see. We got right among the soldiers and killed a lot with our bows and arrows and tomahawks. Crazy Horse was ahead of all, and he killed a lot of them with his war club.” Cheyenne Two Moons recalled the chaos as “all mixed up, Sioux, then soldiers, then more Sioux, and all shooting.”

Читать дальше