Protecting the Herd , by Frederic Remington. Winchesters were standard issue for cowboys and ranchers.

Library of Congress

I love lever-action rifles. I have since I was old enough to chase my little brother, Jeff, around the family house playing cowboys and lawmen. As a matter of fact, I lusted after his Marlin .30-30 when we were kids. I had a fine bolt-action .30-06, but his lever-action Marlin looked to me like a cowboy gun, and in my mind that made it the best.

The whole idea of a lever-action rifle is to slip a cartridge into the breech quickly and easily, so it can then be put to good use by pulling the trigger. The trigger-guard mechanism on the outside of the gun works a lever that pushes the spent cartridge out of the breech when it’s pulled down. Sliding the lever back up snugs a fresh one into place. The inside cogs and springs of the action that get this done are tucked out of sight, of course; all the operator sees and feels is a very satisfying click-click that shouts WILD WEST in capital letters.

The Spencer had been the most successful repeater of the Civil War era, but even so, it did have limitations. The operation came to a full stop after the cartridge was chambered. Before the bullet could fly, the shooter had to pull back the hammer manually, usually with his thumb. Only then was the gun ready to fire.

Wouldn’t it be easier, someone thought, if you could use the same lever that was getting the bullet in place to ready the hammer as well?

Actually, you could. And while it may not seem like that big a deal to someone used to a Spencer, or other weapons of the day, that little touch of simplicity made for a much smoother and quicker shooting process.

As it happens, someone had thought of this setup well before the Spencer reached Gettysburg. The Henry Repeater, such as the model Lincoln tested in 1861, used just such an arrangement. The weapon had other shortcomings, but the ideas behind its action were solid.

In the late 1860s, Oliver Winchester purchased the remains of the company that created the Spencer Repeater. One of the reasons he had the cash to do so was the success of his firm, now known as Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Winchester and company had stayed with the basic design of the Henry, but made so many improvements that the Winchester Model 1866 was really a very different animal. True, it had a bronze-alloy frame like the Henry, and it still used the same rim-fire cartridge. But where the Henry had been more than a tad on the temperamental side, the 1866 was a robust shooting iron. Its red brass or gunmetal receiver had a yellowish tint to it, earning it the nickname “Yellow Boy.” But there wasn’t anything yellow about it. The magazine was sealed. You could load the weapon at the side thanks to a loading gate. There were a bunch of other little improvements that helped the gun stand up to the strains of the frontier.

But it was the company’s next rifle, Model 1873, that earned Winchester its everlasting fame. Again, this was a sturdy weapon, even more so than the 1866. It also used a .44–40 cartridge. This gave the gun more stopping power, while not being so large that it made the rifle hard to handle. It also meant you could use the same ammo in your rifle and Colt Frontier revolver. The Winchester found a sweet spot where power, convenience, and versatility were in perfect balance.

The search for a perfect weapon had been a long, dusty trail, with a number of detours and missteps. It produced some mighty fine weapons, even if none were “perfect.” The ideal weapon depends on the circumstances you find yourself in. Sometimes you want a lot of bullets. Sometimes you want just one big one.

Size did matter on the Plains. American settlers surged westward from the eastern forests and quickly discovered that the original flintlock American long rifles with a .32-caliber ball weren’t powerful and fast-loading enough for the larger game out West. Buffalo, elk, bighorn sheep, grizzly bear, and mountain lion all required guns with bigger loads. And unless you were a skilled contortionist, the American long rifle was pretty awkward to carry and use from the saddle.

So new single-shot, muzzle-loading hunting rifles came on the scene. The most famous Plains rifle was a model made by the Hawken brothers, gunsmiths in St. Louis, Missouri. The Hawkens cut the barrel down to thirty inches, and boosted the projectile to at least .50 caliber. That gave their weapons the power to knock down big animals at long range. On the wide-open plains, accuracy at distance was essential, due to the fact that it was difficult to sneak up on anything. The weapon became a favorite among hunters, trappers, mountain men, traders, and explorers, first as a flintlock and then as a percussion cap gun after 1835. The Hawkens called them “Rocky Mountain Rifles.”

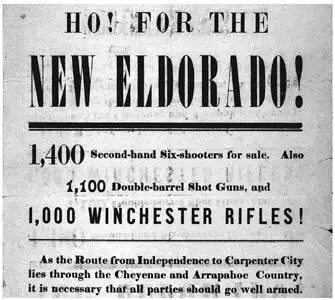

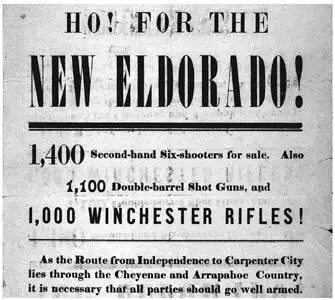

Above: An 1879 broadside boasting its advertiser’s stock of Winchesters to settlers and travelers headed into Indian country. Below: A later Sears and Roebuck ad hawking the latest models.

Library of Congress

But the big daddy of all Plains rifles was the post–Civil War “Sharps Big 50,” the quintessential powerhouse buffalo gun. This piece contributed directly to the shaping of America by powering the final expansion of European settlers across the continent. Its bullets slaughtered millions of buffalo. The consequences were complex and, for Indians as well as the animals, not very pleasant, but the weapon itself was a fine piece of work.

The large-caliber Sharps built on the design and reputation of the single-shot, breech-loading, falling-block Sharps rifle, which had done so well on the field of battle during the Civil War. The new model had center-fire metallic cartridges and a half-inch-diameter projectile. It retained its vertical dropping-block action, which was operated by the trigger guard. The action was not only strong but limited the release of gases when the gun was discharged. The thirty-inch barrel had eight sides, which was not uncommon at the time. I don’t know if that made it stronger or just easier to build, but it did give the weapon a special feel.

The big Sharps had the power to drop a distant buffalo or stop a charging grizzly. It was also highly accurate. The kick was strong, or as the National Firearms Museum in Virginia puts it, the rifle had “knockdown power at both ends.” Elmer Keith, writing about the gun in 1940 after conducting a number of experiments with it, pronounced its recoil “darn heavy” and its report “something to remember,” which I suppose you’d expect from a cartridge two and a half inches long.

The .50 Sharps’ main target was the American bison. Before 1800, much of middle American grassland was a paradise for vast herds of grazing buffalo. Twelve feet long and weighing up to two thousand pounds each, the buffalo were self-service supermarkets for the several hundred thousand Native Americans. Their carcasses provided not only food, but also clothing and shelter. They even served up raw materials for war shields, boats, fuel, and glue. As many as 50 million buffalo remained on the Plains in 1830, split into northern and southern groups. A single herd of roughly 4 million was spotted as late as 1871.

For the arriving white settlers, the buffalo were a cash machine: hides fetched a hundred dollars each. Among other things, the leather from the animals was being used to make belts for commercial sewing machines and other equipment as the Industrial Revolution expanded. The animals were just one more raw material. But as they vanished, so would the people who depended on them.

Читать дальше